Incidences of unsafe sex are up, while new infections remain stable

From 2000 to 2003, syphilis cases in New York City went from 117 to 531 and more than 95 percent of those cases were among gay and bisexual men.

Rectal gonorrhea among men went from 31 cases in 1999 to 120 cases in 2003, according to city health department data. These increases in sexually transmitted diseases are clear proof of men having unsafe sex, behavior which also makes it easier to transmit or acquire HIV.

Gay men in the Big Apple continue to use illegal drugs — crystal, ecstasy, special K — and legal ones, most notably alcohol, that are associated with unsafe sex.

All the elements are in place for New York to see an increase in new HIV infections among gay men, but the rate of new infections among those men has remained stable for a decade.

“The ingredients are all there,” said Dr. Lucia V. Torian, director of the HIV epidemiology program at the city health department.

The HIV incidence rate, the percentage of people who are newly infected in a year, among queer men has hovered at two to three percent from 1993 to 2002, according to the health department’s best estimates. “The good news is it’s not going up,” Torian said. “The bad news is it’s not going down.”

The incidence rate in both 2001 and 2002 was 2.4 percent. While that seems low, incidence is cumulative. After ten years at a 2.4 percent rate, 24 percent of the group being tested would be infected.

Researchers offer a number of possible explanations for that stable rate. An obvious one is the effect that anti-AIDS drugs have on reducing the amount of HIV in the blood of infected people. Those individuals are less likely to transmit the virus.

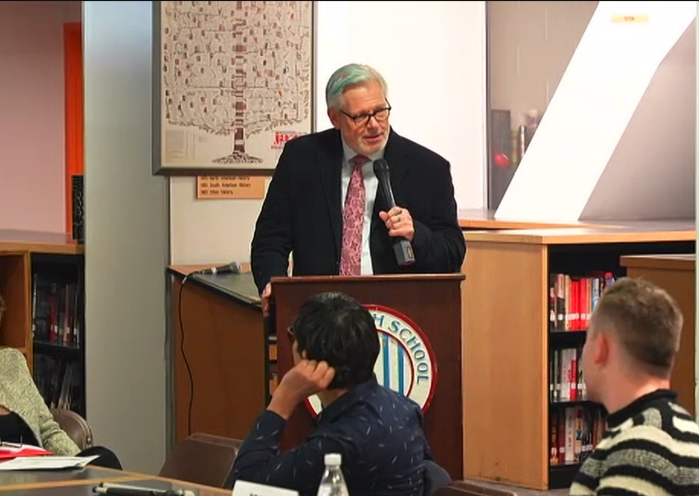

“There is no question that it lowers viral load,” said Dr. Mary Ann Chiasson, vice president of research and evaluation at the Medical and Health Research Association of New York City. “[Viral load] is the strongest correlation with transmission. You would assume that it has got to be having some impact.”

As more people take those drugs, “community viral load,” as Torian put it, is reduced. There is simply less virus available to infect people. “The effectiveness of treatments is extremely important,” said Dr. Ronald O. Valdiserri, deputy director at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for HIV, STD and Tuberculosis Prevention.

Valdiserri said that some theoretical models have suggested that with widespread treatment and no increase in unsafe sex, incidence could fall.

“If enough people are treated and the frequency of sexual behavior is stable, there will be a decrease,” he said. It may be that gay and bisexual men are engaged in what health experts refer to as “sero-sorting.” Guys who are not infected may reject men who are HIV positive or they may engage in acts, such as oral sex, that are less likely to transmit HIV. “Some of the behavioral scientists think that might be happening,” Valdiserri said. “Men might be choosing by HIV status or they might be engaging in sexual practices that don’t have a high likelihood of transmitting HIV.”

A recent study from the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training (CHEST) showed evidence of sero-sorting among its 183 participants. Men in the study who were uninfected had much less sex, either anal or oral, with casual partners they knew to be positive.

But sero-sorting relies on a sex partner knowing his status and being honest about it. The negative men had more receptive anal sex, the riskiest kind of sex, when they believed their partner was also negative or they did not know their partner’s HIV status. “You can have a situation where somebody thinks they are engaged in sero-sorting, but because the other person doesn’t know their status or isn’t honest then you have the opportunity for transmission,” said Dr. Jeffrey T. Parsons, a co-director at CHEST and a psychology professor at Hunter College.

Despite reports of widespread unsafe sex among queer men, it may also be that, at least some of those men are using condoms and having safe sex. That might explain the current syphilis and gonorrhea rates.

Rectal gonorrhea went up 300 percent between 1999 and 2003, but in 1980, at the start of the AIDS epidemic, New York City had 1,869 cases of male rectal gonorrhea. Incidences of syphilis infection have recently increased dramatically, but they reached their most recent peak in 1988 at over 5,000 cases.

“Although we’ve seen a big increase in syphilis recently it’s nowhere near where it was 20 years ago,” Chiasson said. “It does suggest that there have been big changes in behavior. More people may be using condoms, more people may be having fewer partners, more people may be having sequential versus concurrent partners.”

Parsons agreed and made the point that not every gay man who has sex with many partners is a meth-addicted or sexually compulsive person. “There are perfectly, psychologically healthy men out there who are having a lot of sex and are safe and enjoying it,” he said.

Community norms may have changed. In the late 70s, the ethos of sexual liberation celebrated sexuality and urged its proponents to have lots of sex with many partners in bathhouses, backrooms of bars and clubs. There are few advocates of sexual liberation alive today and, in some circles, an unbridled sexuality is seen as a problem, not a cause for celebration.

Currently, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center lists 28 weekly meetings of Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (SCA), a group that did not exist in the late 70s. The next closest group is Alcoholics Anonymous with 15 weekly meetings. “Relationships are more common now,” Parsons said. “They are more accepted…I think what’s happened in the community is that we have different norms. We have some norms that are very opposed to risky sex and having lots of partners. There are other norms that support barebacking and lots of partners.”

Nevertheless, these researchers are warning against complacency. HIV incidence among gay and bisexual men could still rise. “From a public health point of view our feeling is that there are many factors in place that would lead to a resurgence, but we can’t say that a resurgence is happening,” Valdiserri said.

Chiasson lived through the first years of the AIDS epidemic when the disease took the lives of tens of thousands of men. A study of stored blood samples from that time investigated the HIV incidence rate then. In 1978, it was 6.6 percent among gay and bisexual men. It increased in later years.

“What they found when they looked at these stored samples was that the annual incidence of sero-conversion was between 5.5 percent and 10.6 percent,” Chiasson said. “You can see how the epidemic got started.”

Struck down behind those numbers are the lives of many gay men that were cut short by AIDS. Today’s incidence rate does not give Chiasson hope. “It’s very worrisome that there is as much transmission going on that there is,” she said. “I sat one day and I took out all of the cards in my Rolodex of all of the men who died. To think that we might have to go through this again is very disturbing.”