When somebody mentioned “The Church” in the New York City of yesteryear, that said it all. The Church was the Catholic Church and the cardinal spoke for it. The Church commanded awesome power in the city and in Albany, and yet the maturing of the gay rights movement and the emergence of AIDS grassroots direct action — both coming during the 1980s — would prove that it was no longer invincible.

For many decades, the Legion of Decency had told Catholics if a movie was good for them, but it was so anti-sex that ridicule over time made its ratings lose their sting. The pill made sex safer for heterosexuals and their sexual revolution preceded the blossoming of gay rights visibility. In the early 1970s, the Church failed to stop Albany from repealing the ban on abortion.

Years that the Church spent blocking a New York City gay rights bill collapsed in 1986 when City Council Majority Leader Thomas Cuite retired, and his successor, Peter Vallone, allowed a vote to take place. In a 21 to 14 vote on March 20 of that year, the measure passed after a decade and a half of organizing.

The climate, however, had not shifted unambiguously for the better. Two days before the Council approved the gay rights measure, The New York Times published an op-ed by William F. Buckley, a conservative giant — and a Catholic — arguing, “Everyone detected with AIDS should be tattooed in the upper forearm, to protect common-needle users, and on the buttocks, to prevent the victimization of other homosexuals.” Others spoke darkly of quarantining those with HIV, or homosexuals generally.

And in June 1986, just three months after the Council victory, the US Supreme Court, in a vitriolic majority opinion, upheld state sodomy laws, giving renewed life to the notion that homosexuality is a crime. Hatred and damnation had received a wink and a nod from the nation’s highest court.

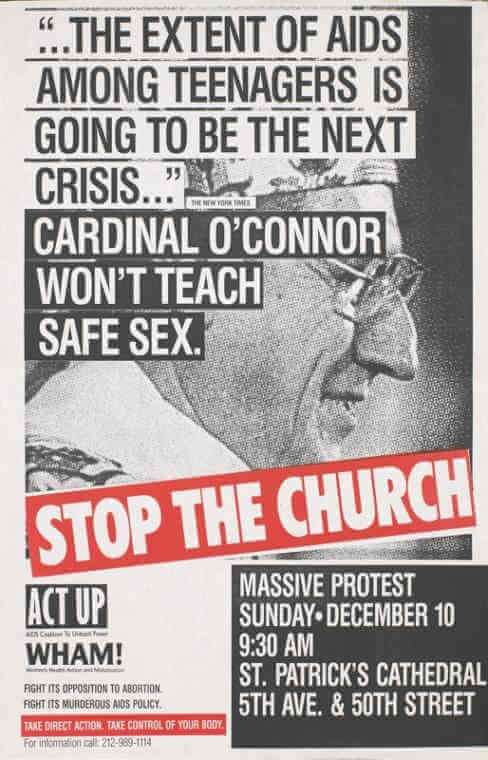

Even before ACT UP was founded, activist Michael Petrelis was using his booming voice to shout, “You’re killing us.” This past Sunday, Petrelis was back in New York from his home in San Francisco to lead the of 30th anniversary remembrance of the December 10, 1989, Stop the Church demonstration at St. Patrick’s Cathedral where thousands of ACT UP and Women’s Health Action and Mobilization (WHAM!) members protested the Church’s intransigence on gay and AIDS issues, with some entering the Sunday Mass to cuff themselves to the pews or lie on the ground.

Even before that controversial demo, Petrelis had already for years been committing an even more courageous action — living as an openly HIV-positive person, working with the Lavender Hill Mob, a precursor to ACT UP. For him and many others, fighting shame and ostracism, demanding health care, and slamming high drug prices were urgent issues facing all gay men.

In their book “Out for Good,” Dudley Clendinen and Adam Nagourney point to a May 13, 1986 cover story in The Advocate, the community’s slick newsmagazine, titled “The AIDS Slur: Why Gays Should Stop Taking the Blame and Start Fighting Back,” which argued, “We’ll survive only if we stop apologizing — for AIDS, for our loves, our lives. We’ll survive if we let loose our rage.” The article Clendinen and Nagourney noted, “bristled” with a rage that “would soon become familiar to the entire world.”

A year later, in a March 10, 1987 speech at the LGBT Community Center widely viewed as the launch of ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, Larry Kramer said, “If my speech tonight doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in trouble.” ACT UP became the go-to place for AIDS activism.

ACT UP brought together activists of widely varied talents. If Petrelis epitomized the brassy demonstrator unafraid to damn the establishment, Avram Finkelstein, the art director at Vidal Sassoon, worked with other artists to design posters — including the pink triangle and Silence=Death designs that made an indelible mark on the public imagination. Snipers, the folks who posted ads on building walls for rock and disco clubs, posted ACT UP art all over the city. Other ACT UP members studied the science and the public health bureaucracy that controlled drug testing, gaining expertise upon which government scientists over time came to rely.

It was through this collective effort that ACT UP gained its prominence in the fight against AIDS, becoming a key referee in alerting the public as to who was contributing to a solution and who was standing in the way. The group slammed the drug companies, forced the government to spend money on prevention, treatment, and care, and damned those who declared that people with AIDS were evil.

Among these foes was Cardinal John O’Connor, New York’s archbishop from 1984 until 2000.

Ann Northrop, the co-host of USA Today, joined the St. Patrick’s demonstration because the cardinal “was telling the general public that monogamy would protect them from HIV infection and that condoms didn’t work. As far as I was concerned, these were both major lies that were going to kill people.”

According to Charles Kaiser, author of “The Gay Metropolis,” even critics of those protesting a church service — including the gay Catholic group Dignity — agreed that O’Connor’s position was immoral.

O’Connor’s supporters and many other mainstream observers condemned ACT UP’s 1989 action at St. Patrick’s, yet the group managed to put the cardinal on the defensive and made the nation rethink sex-negative advice. Activism forced a better understanding of how the virus worked and of the vital importance of condoms. When all the dust had settled on a very controversial day that December, it was the Church struggling to justify its posture.

By 1990, the focus on condom use encouraged a new public health appreciation for harm reduction as way of reaching people with useful prevention tools suited to their lives. Thirty years ago, that was a matter of survival, not only for gay men but for many others affected by the spread of HIV, as well. Today, HIV isn’t the killer it once was, but hatred remains lethal, particularly for transgender people — and most especially for trans women of color. Public attitudes toward the LGBTQ community have changed dramatically, but policy still matters. And in Washington every day, we see the way that regressive policies embraced by the Trump administration mean we cannot let our activist guard down.