What if the Mexican Revolution hero Emiliano Zapata was an effeminate gay man? We at least know what his family would think.

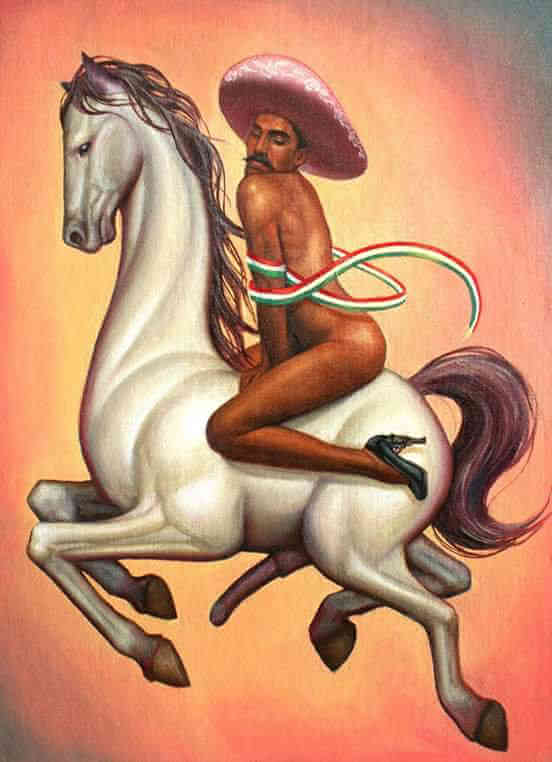

Wide resentment has ensued since artist Fabián Cháirez’s depiction of Zapata — a heroic military figure assassinated while leading a movement of farmers against wealthy landowners during the Mexican Revolution of 1910 through 1920 — as naked and effeminate in a painting came to wide attention. The piece of art shows Zapata sitting on a horse, wearing high heels, and donning a pink-colored hat. A ribbon with the red, white, and green of the Mexican flag is wrapped around him and blowing in the wind, and the end of the ribbon is sparkling. Imagery of Zapata typically shows him in a completely different way: as a strong, masculine leader known to carry a rifle and sword.

Zapata’s family has mounted resistance to the painting and is threatening to sue. His grandson, Jorge Zapata González, said the family would “not allow” the painting and that the piece of art “denigrates the figure of our general [Zapata], depicting him as gay,” according to the Associated Press.

A group of individuals on December 10 flocked to the Palace of Fine Arts, where the painting resides, to protest it and chant, “Burn it, burn it.” The protestors included farmers who look up to Zapata because of their shared experience as men working the land and struggling to financially sustain themselves. NPR reported that the farmers were chanting homophobic slurs while protesting.

Cháirez completed the painting in 2014, but it did not generate significant attention until the Mexican government’s Ministry of Culture recently opted to display it in an exhibition marking the 100-year mark since Zapata died.

Cháirez was motivated to illustrate the painting the way he did because “Zapata’s masculinity is glorified,” according to BBC. He explained that the painting is intended to generate conversations about gender norms in society.

“There are some people who experience discomfort from bodies that don’t obey the rules,” Cháirez said. “In this case, where is the offense? [The protesters] see an offense because Zapata is feminized.”

The exhibit’s curator, Luis Vargas, downplayed the concerns of protestors, saying that the painting was just a form of artistic expression.

Zapata was murdered in April of 1919 — one year before the conclusion of the Mexican Revolution — when he thought he was headed to a meeting, but wound up getting shot to death by his opponents. His legacy as a working class hero who sought progressive land reform has continued to live on in political campaigns, historical accounts, and art, and his reputation has grown since his death.

To this point, protestors have been unsuccessful in their efforts to tear down the painting. The exhibit is slated to remain until February of next year.