A nostalgic lens for real queer experience

McDermott & McGough

“A True Story Based on Lies”

Cheim & Read

547 W. 25th St.

Jan. 12-Feb. 11

Tue.-Sat. 10 a.m. – 6 p.m.

212-242-7727

Time travel is not so much a scientific fiction as it is a romantic one. The overriding desire is not to prove that time travel is technologically possible as in “Terminator” or “Back to The Future,” rather the urge is to revisit a missed opportunity or unrealized desire as Kathleen Turner did in “Peggy Sue Got Married.” As a self-professed romantic fool, I rarely pass up the chance to see “Somewhere in Time” in which an impossibly handsome Christopher Reeve travels from the 1980s to the turn of the 20th century to romance Jane Seymour. Reeve doesn’t rely on science to propel him back but accomplishes the feat through self-hypnosis and by surrounding himself with the trappings of the past, hiding from view any suggestion of the present and dressing in period costume. Reeve’s character willingly suffers in the romantic delusion that he doesn’t belong in the modern world.

Like Reeve’s character in “Somewhere in Time,” David McDermott and Peter McGough in their life and work extinguish all traces of the modern. You can often see them strolling along the faintly antique streets of Greenwich Village dressed in late 19th century finery. Their reputation as time travelers isn’t just about dress up. Their home is styled as if Victoria still reigned. Their crafted life is an example of the Wildean dream in which art and life become one.

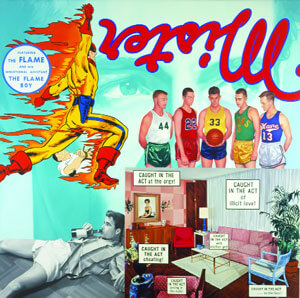

In their appropriation of Victorian and post-war imagery in painting, photography, and installation, McDermott & McGough have made nostalgia the lens through which queer experience is revealed. Their latest exhibition of painting called “A True Story Based on Lies” is a journey into pop visual culture of 1950s and 1960s America. “Famous Fantastic Mysteries” (1965, 2005) sets the tone of the exhibition by yelling pulp alarm and dread with cartoon captions like “Strange Horror” and “Stolen Sweets, “Exciting,” “Terror Tales,” and “Shock,” which bracket scenes of an axe wielding maniac about to chop of the head off a beautiful blond woman, and of a man and woman falling to their deaths. Other works are perhaps less shocking but are visually complex. In “The ‘Warm’ Friendly Feeling Embodied in a Red-Pink One” (1964, 2005) the artists have painted open-ended scenes with the lurid and dramatic color of pulp fiction novels and notated them with sensationalistic tabloid text. The images are a mix of what any hot-blooded and horny 1950s gay teenager would have posted on his bedroom wall—basketball players stare at a ball as if it would offer up answers to sexual mysteries, a muscled and flaming superhero races to the rescue, a young man who’s almost a dead ringer for Jack Kerouac lies on the floor, wine bottle in hand and sprawled out in a promising position. The artists pack in and mix up a range of seductively homoerotic and art historical references that seamlessly weave fantasy into real life so that you would swear you’ve seen these events somewhere before but can’t quite remember where or when.

Does real queer experience only lie in the past? I think anyone would be hard pressed to find fiercely creative views of modern gay life in contemporary art or visual culture. “Brokeback Mountain” depicts the lives of two lonely, repressed ranch hands in 60s America and is on the verge of wining the award as the example non-plus ultra of queer romantic fantasy. Place that story in 2006 in an urban context and the well of tears shed for failed romance would probably dry up. Perhaps today’s gay men get more pleasure from the masochistic pleasure of sexual repression or in the novel experience of a less gay and arguably more erotic past. Is modern gay culture so unbearably dull and uninspired? McDermott and McGough nostalgic trips through American history seem to argue this point more fiercely than any other gay artists by their refusal to acknowledge the present.

In McDermott & McGough’s “The ‘Warm’ Friendly Feeling Embodied in a Red-Pink One” (1964, 2005), oil on linen, the artists pack in and mix up a range of seductively homoerotic and art historical references that seamlessly weave fantasy into real life.

gaycitynews.com