As it neared the end of its 2019/ 2020 Term, the US Supreme Court issued two First Amendment rulings of particular interest to the LGBTQ community.

One will make it more difficult to use federal funds to fight the spread of HIV overseas, and the other continues the court’s trend of allowing taxpayer money to subsidize religious organizations.

Supreme Court hinders HIV prevention work overseas, gives green light to public funding of religious schools

In both cases, the court’s majority was made up entirely of justices appointed by Republican presidents and the dissenters were all appointed by Democratic presidents.

Fighting HIV Overseas

On June 29, the court rejected by a 5-3 vote an attempt by the Alliance for Open Society International, a US organization, to free its overseas affiliates from a statutory requirement that they officially state a policy against prostitution in order to access federal funds targeted at combatting the spread of HIV.

The federal program, adopted in 2003, is the United States Leadership Against HIV/ AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act.

Congress placed two restrictions on organizations receiving money under this law: that they not promote prostitution or sex trafficking, and that that they have a “policy explicitly opposing prostitution and sex trafficking.” This provision was attributed to congressional findings that prostitution and sex trafficking contribute to the spread of HIV.

Organizations seeking to curb the spread of HIV overseas have argued, quite logically, that a key element of their strategy is to win the confidence of sex workers in order to provide them with health care and to supply training in the use of condoms. Having a policy explicitly opposing prostitution was inconsistent with this mission, they have pointed out.

The Alliance for Open Society found that in many countries the local governments insisted that the money flow through locally chartered organizations, so the Alliance created affiliated organizations in many of the countries where it was doing HIV prevention work.

As soon as the law was passed, the Alliance went to federal court seeking a ruling that it had a right under the First Amendment to refuse to adopt an explicit anti-prostitution policy, and it succeeded at the Supreme Court. In 2013, the court ruled that any attempt to enforce this requirement against the Alliance was a violation of its free speech rights.

After that ruling came out, however, the government insisted that the Alliance’s overseas affiliate organizations could not receive US funds unless they adopted policy statements in compliance with the 2003, and the Alliance headed back to court seeking a ruling that the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision applied to its foreign affiliates.

The affiliates are clearly identified as operations of the Alliance for Open Society, and lower federal courts agreed that it violated the First Amendment to require them to adopt an anti-prostitution policy.

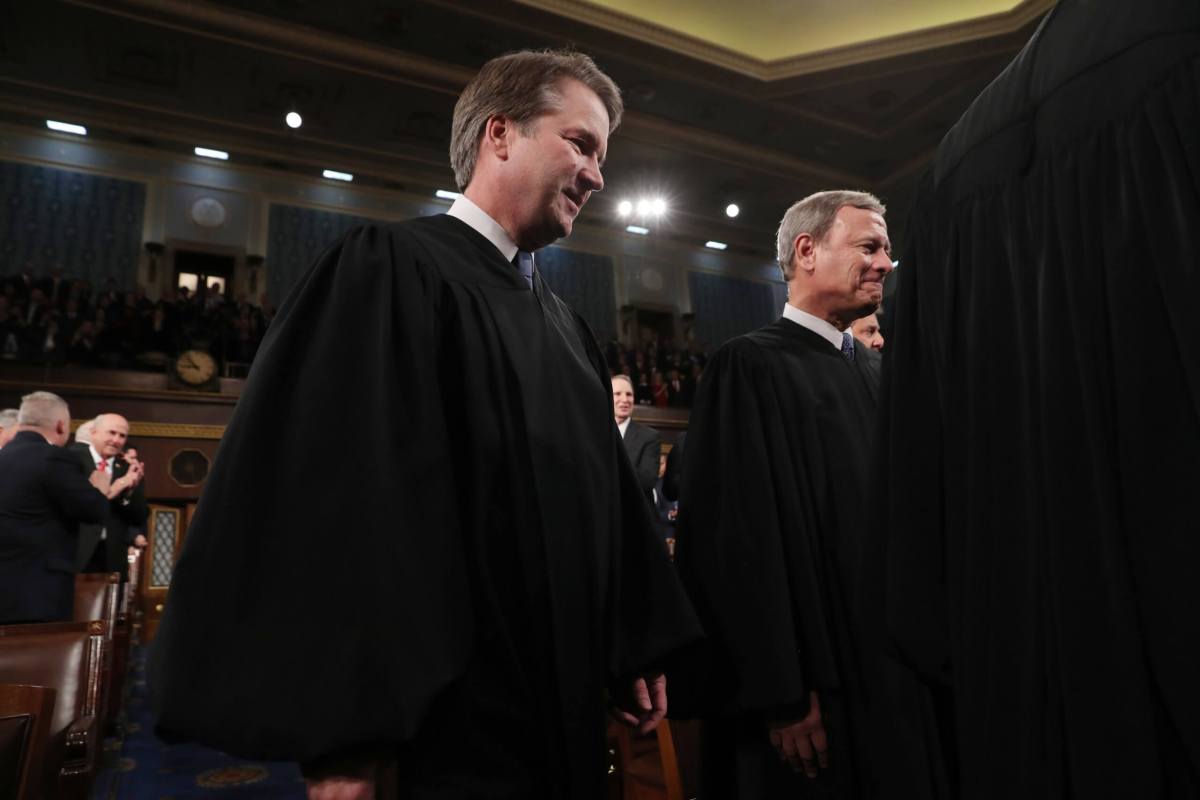

Writing for the court, Trump-appointee Brett Kavanaugh stated that it was a well-established precedent that the First Amendment protects the free speech rights of Americans and American organizations, but has no application to the speech of foreign nationals and organizations operating outside the US. He concluded there was no First Amendment violation.

All five conservative justices voted for this result, with Justice Clarence Thomas concurring on the ground that he thought the restriction was perfectly valid as applied to any recipient of federal funding, not just the overseas affiliates.

Justice Stephen Breyer dissented for himself and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor. Justice Elena Kagan, who had been involved in this litigation as US solicitor general during the Obama administration, recused herself from the case.

Breyer argued that the court’s opinion mischaracterized what the case was about. The dissenters agreed with the Alliance that applying the restriction to its foreign affiliates abridged its own First Amendment rights, since creating those affiliates was the only way it could carry out its HIV prevention work in many countries. Requiring the affiliates to affirmatively oppose prostitution, likely driving sex workers away from participating in the program, was undermining that mission.

Government Funding of Religious Schools

In the second opinion, announced on June 30, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, the court continued its trend of broadening the potential scope of government financial assistance to religious organizations.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the five-member majority, with the more liberal justices all dissenting.

Montana enacted a law to increase parents’ ability to send their children to private schools. Taxpayers could make tax-deductible donations to a scholarship organization, which would then award scholarships to students who were attending any private school that met state educational criteria. The “school choice” statute made no distinction between religious and non-religious private schools. Not surprisingly, about 94 percent of the applications were for scholarships to attend religious schools, so this was essentially a way for the state to channel money into religious schools. The State Legislature appropriated millions of dollars to fund the tax credit program for the only scholarship organization that went into operation under the law.

The Legislature specified that the program had to comply with the Montana Constitution’s provision that prohibits the government from providing “any direct or indirect appropriation or payment from any public fund or monies to aid any church, school, academy, seminary, college, university, or other literary or scientific institution, controlled in whole or in part by any church, sect, or denomination.”

Presumably, the Legislature concluded that providing this money in the form of scholarships to students instead of directly funding the religious schools would not violate this provision, since they would be directly aiding the students and their parents.

However, the Montana Department of Revenue subsequently adopted a regulation that the scholarships could not be used to attend religious schools. The state’s attorney general opposed that regulation’s adoption and refused to defend it in court when some parents who were told their children could not use the scholarship money to go to a religious school sued the Department of Revenue, claiming this violated their free exercise of religion.

The Montana Supreme Court found that the scholarship program violated the State Constitution because it authorized spending state funds for “any” qualified school, without excluding the religious schools. That court put an end to the entire program.

The parents appealed to the US Supreme Court, claiming again that their right to free exercise of religion was being violated.

The US Supreme Court had two prior precedents that could have applied here. In one, the court held that a state did not violate the free exercise clause when it set up a scholarship program that explicitly excluded any assistance to students studying to be clergy. In the other, it ruled that a state program to assist organizations in repaving projects could not deny participation to religious organizations. The money would be spent to repave parking lots and playgrounds, not for religious instruction, the court noted.

Ruling for the parents in this case, Roberts said that the decision was controlled by the paving case. As in that case, he wrote, the state may not discriminate against religious organizations under a general benefit program. While the state is under no compulsion to fund religious education, if it sets up a general scholarship program to provide financial assistance to parents who want to send their children to private schools, it can’t single out private religious schools for exclusion.

Roberts was joined by the other conservative justices, some of whom wrote concurring opinions. Justice Samuel Alito emphasized that the Montana constitutional amendment relied on by the State Supreme Court was one of a wave of such amendments passed by Protestant majorities in the late 19th century in response to the massive immigration from Europe of Catholics to prevent any governmental subsidy to Catholic schools. He saw these amendments as being conceived in anti-Catholic bigotry, and thus clearly violating the First Amendment by discriminating against a particular religion.

Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor each filed dissenting opinions, and Kagan joined in some of the dissents.

The dissenters saw the clergy scholarship precedent as controlling here. Students attending a religious school are going to be getting religious instruction, so it is clear that any state financial assistance flowing to the school through the scholarship program is financing religious education. The data showing that scholarships under the program were almost all going to religious schools made clear that it was intended primarily to subsidize religious education.

Some of the dissenters also pointed out that since the Montana Supreme Court ended the entire program, there was no discrimination being practiced against religion.

Roberts, in his majority opinion, pointed out that since no Establishment Clause claim was made in defending against the parents’ lawsuit, the Supreme Court had not been asked to address the question whether a state program channeling significant money to scholarships for students attending religious schools violates the Establishment Clause.

The First Amendment religion clauses present a constant tension between free exercise rights and the ban on the establishment of religion. Many scholars have long embraced the notion of church and state separation described by the republic’s founders who had rebelled against an empire with an established church funded by the government. But the Supreme Court, with its conservative majority since the Reagan administration, has adopted a very limited view of the Establishment Clause and an expansive view of the Free Exercise Clause.

There is one notable exception, however, a 1990 ruling, Employment Division v. Smith, in which Justice Antonin Scalia — interestingly enough — writing for the court, held that the Free Exercise Clause does not excuse people from complying with general state laws that are religiously neutral just because the laws incidentally may place a burden on an individual’s free exercise of their religion.

This principal was invoked by Justice Anthony Kennedy in one of his last opinions for the court, the June 2018 Masterpiece Cakeshop decision, when he wrote that individuals don’t have a general right to refuse to comply with anti-discrimination laws based on their religious beliefs. (The baker refusing to make a wedding cake for a gay couple, however, prevailed, on narrow grounds, because the court found that the Colorado commission reviewing the case evidenced hostility to his religious views.)

This principal will be tested next term when the court hears the case of Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, a challenge by Catholic Social Services to the city’s action cutting it off from participation in Philadelphia’s foster care program because it won’t provide its services to same-sex couples. Several of the conservative justices have already called for reconsideration of Employment Division v. Smith as part of their general agenda to broaden protection for free exercise of religion.

If Scalia’s opinion in that case is overruled, employers with religious objections to hiring LGBTQ people may find an enormous loophole in the Title VII protection that was so hard-won on June 15.

Stay tuned.