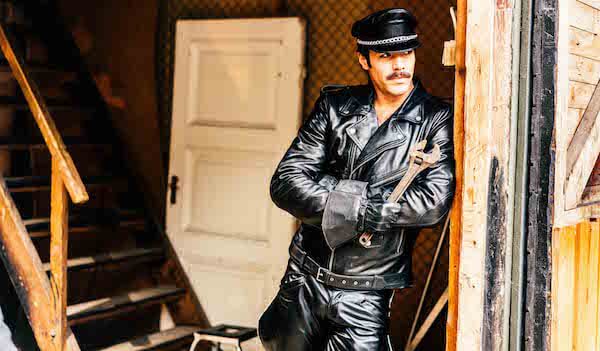

Once upon a time, gay men walked the streets of New York and San Francisco, alone and in bands, clad in uniforms that appropriated the roles and rubrics of straight male aggression and dominance. Their garb was inspired by sundry military men and blue-collar workers, and their silhouettes and stances became the vocabulary of urban gay masculinity. Soon, these clones, as some dubbed them, were cropping up in the gay villages of other major American cities, and eventually elsewhere in North America and western Europe, such as Amsterdam, London, and Montreal. Erotic, yes, but there was also something clearly didactic and pedagogical about this aesthetic. Here were gay men teaching each other and the straight world what a gay man looked like.

One of the headmasters in this schoolhouse of sexual stylization, as queer theorist Judith Butler would describe it, was an artist named Touko Laaksonen (1920-1991), better known as Tom of Finland. Laaksonen’s explicit drawings of men bulging out of uniforms, leather gear and work duds, many carousing and copulating in pairs and groups, committed gay bodies to the pages of magazines that circulated in the international gay subculture beginning in the 1950s. Over the ensuing decades, his illustrations swelled in appeal and acclaim, making the art of Tom of Finland a genre onto itself, displayed in art galleries and held in the collections of some of the world’s foremost museums.

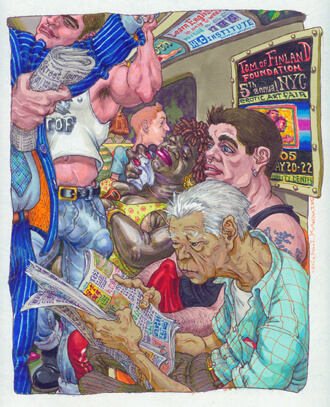

Now, on the centenary of Laaksonen’s birth, Fotografiska, New York presents the exhibition, “Tom of Finland, The Darkroom” from April 30 to August 20.

Tom of Finland is known as an illustrator. But, he also took photographs to inspire his drawings.

Hence the premise of this exhibition — it is the first to frame Tom of Finland as a photographer. Out of necessity in sexually repressive Finland of the 1950s, Laaksonen set up a darkroom in a closet of his home in Helsinki to develop the racy photographs he took of men. These images, being not only pornographic but homoerotic, were outlawed at the time, and he couldn’t entrust the negatives to anyone else to develop for him. Even after developing the prints, Laaksonen destroyed several to protect the subjects in them, most of whom were his friends and lovers.

“The Darkroom” presents photographs and photographic collages that have never been publicly displayed.

“I feel really humbled that we were able to show a totally different side of this very well-known artist,” said Berndt Arell, the exhibition’s curator, in a virtual walkthrough of the show when it was first unveiled last year at another of Fotografiska’s locations, in Tallinn, Estonia.

The exhibition visualizes Laaksonen’s long history of international interaction that greatly informed the Tom of Finland oeuvre. Raised by schoolteacher parents in rural Finland, he served in the Finnish army during World War II and “had a lot of sex with a lot of soldiers” from among the occupying German and Russian troops, said Arell. “It was a fetishism about uniforms — that they are very masculine and very handsome. He really loved them. All kind of uniforms.”

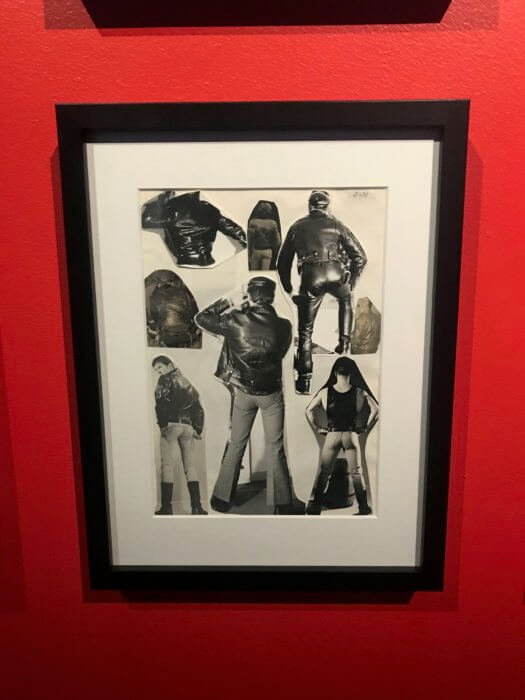

Later, Laaksonen drew inspiration from American bodybuilding magazines and, in time, leather fetish gear.

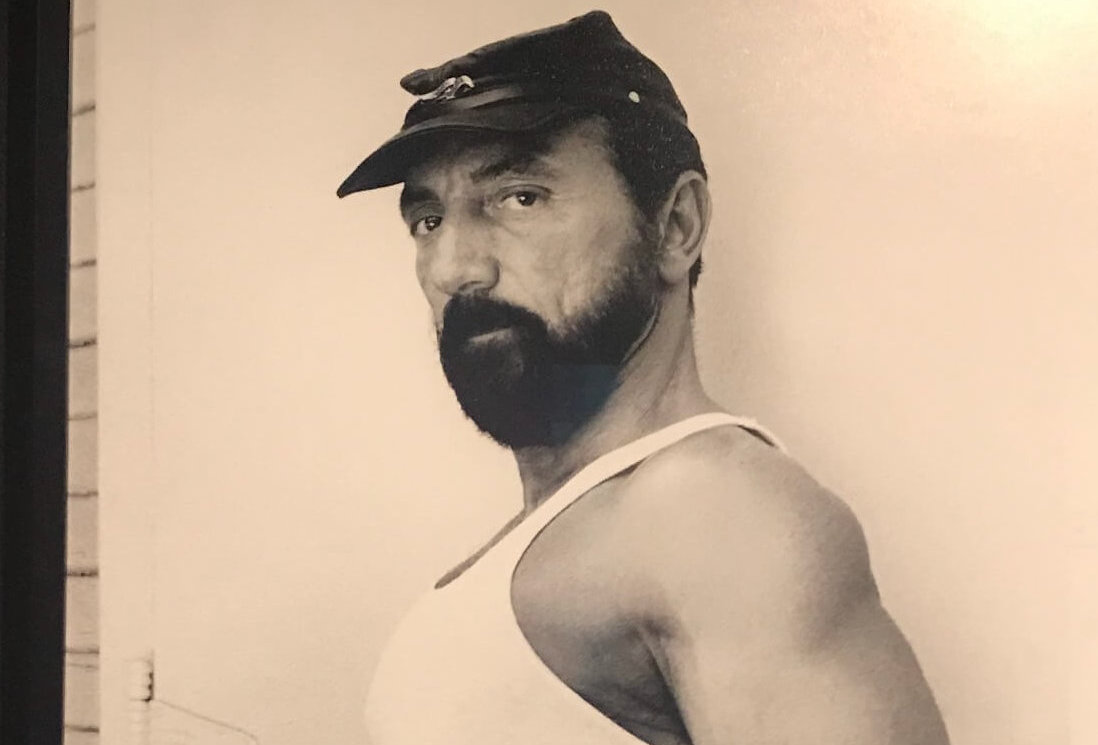

The first images in the show the visitor encounters are photographic portraits Laaksonen and Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989), the New York-based gay photographer also immersed in underground gay aesthetics, took of each other in 1976. Mapplethorpe was an admirer of Tom of Finland’s artwork and traveled to Helsinki to have Laaksonen draw his own portrait. The photos Laaksonen took of Mapplethorpe on which to base his drawing, also displayed, detail the collaboration between two of gay visual culture’s most important artists.

There are several portraits in “The Darkroom” of Laaksonen’s intimates and confidants, including one of Arno, Laaksonen’s favorite muse. Laaksonen based his figuration of the archetypal Tom of Finland character on Arno’s aesthetic, attitude, and physique.

In the photograph, “Arno is wearing all the fetishist details that interests Tom,” Arell points out. “Like the leather boots, the uniform shirt and the harness and the cap, of course. And the moustache. Everything. He’s perfect. This is really Tom’s man.” The shadow Arno’s profile casts on the wall behind him is indeed the epitome of a Tom of Finland face.

Laaksonen eventually relocated to Los Angeles. He found the men of that city, both close and unknown to him, stimulating. The Tom of Finland Foundation, from whose extensive holdings the photographs and artworks for this show were selected, is housed in Laaksonen’s former L.A. residence.

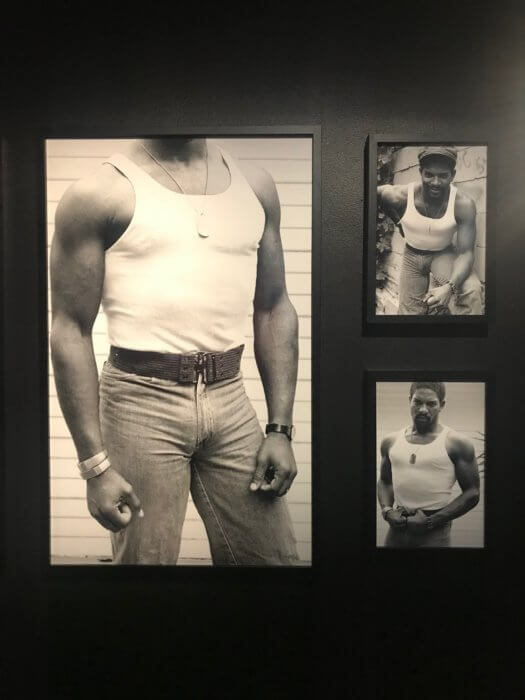

Perhaps not surprisingly given his fixation with hypermasculinity, Laaksonen took an interest in Black men, long characterized as preternaturally virile. One collection of photographs in the show, “Untitled 1986,” is of an African American subject, the largest of which is a close study of the man’s body cropped at the neck and just above the knees, his bulging crotch the central point of attraction, reminiscent of Mapplethorpe’s controversial piece, “Man in Polyester Suit” (1980). Many Tom of Finland illustrations came to feature Black characters or interracial sex scenes. These photographs introduce one human model Laaksonen picked to help him create the iconic illustrations that are now relics of a bygone era in gay self-fashioning.

“Nobody knew about this material,” said Arell. “You have maybe to rethink your picture of Tom of Finland, of Touko Laaksonen.”

“Tom of Finland, The Darkroom” | Fotografiska, New York | April 30 – August 20, 2021.

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is an associate professor of media studies at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY), and author of “The Amorous Migrant: Race, Relationships and Resettlement” (Temple University Press).