I landed in London the day the people of Britain, once a colonial power that ruled two-fifths of the planet, voted for a government hell-bent on isolating itself from the rest of the world. After a great couple of weeks reviewing plays — some created in direct response to this historic moment — I’m left with the conviction that the world will be better off with the UK sealed off at its shores given the damage it has done over the centuries. That said, theater remains its most precious resource and must continue to be exported.

Brian Friel’s “Translations” (now closed) at the National’s Olivier starring Ciarán Hinds and directed by Ian Rickson, is a reprise of their hit 2018 production. We’re in the 1830s Ireland — already more than 670 years into English interference and domination. Hinds is Hugh, an aging failed rebel coping with oppression by running a local “hedge-school” (outside of Anglican Church control) for a motley crew of broken people. His practical young son Owen (fine Fra Fee) is trying to make the most of the foreign occupation by working with the British military to map and name (often re-name) Irish towns and move the inhabitants from the Irish to the English language.

When love blossoms between an Irish lass, Maire (Judith Roddy), and a young British solider (Jack Bardoe) — in a sweet and erotic scene — the jealousy of Hugh’s other son Manus (Seamus O’Hara), who is devoted to her, and the disappearance of the soldier give Friel the chance to dramatize just how brutal the occupiers could be when crossed. It is a heartbreaking conclusion that elicits real hate for the British — boldly performed in the heart of the UK capital’s own National Theatre (where artistic director Rufus Norris is firing on all cylinders).

A more contemporary indictment of British colonialism comes in a searing “Three Sisters” (“after Chekhov”) at the National’s Lyttelton (to Feb. 19) by Inua Ellams. This is not the Russian play, but a vibrant new one set in Nigeria shortly after independence in the 1960s at the home of an upper middle class family in the eastern region that as Biafra tried to separate itself from the “pressure cooker” of unrelated tribes, villages, and regions the British created to leave behind a divided country that British Petroleum could still control.

There are echoes of Chekhov in the sisters — teacher Lolo (Sarah Niles), Udo (Racheal Ofori), and Nne Chukwu (Natalie Simpson) and supporting characters — but the multi-layered play moves from concern over losing an estate to fear for their lives and country. This is powerful stuff — again rubbing the noses of a London audience in the deadly consequences of the UK’s arrogant exploitation of foreign lands and cultures.

Every performance is so vivid and the drama so compelling that the more than three hours zip by. Special kudos to Anni Domingo as the old family servant Nma who leavens the play with down-to-earth humor and wisdom. And Ken Nwosu as Ikemba, the commanding general who loves Nne and is philosophical: “We are not meant to be happy but to long for happiness.” Cold comfort when the woods are burning.

Director Nadia Fall’s next play is her own “Welcome to Iran” at the National in 2020. Can’t wait.

“My Brilliant Friend” at the National’s Olivier (to Feb. 22) is April De Angelis’ harrowing and thrilling adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s best-selling books directed by the ever-inventive Melly Still who with a minimal, flexible set but evocative costumes (both by Soutra Gilmour) create an Italy we rarely glimpse — despite the groundbreaking postwar cinema of Fellini and De Sica — and almost never from a feminist perspective.

Lenu (Niamh Cusack) and Lila (Catherine McCormack) — remarkable characters and actors — meet very inauspiciously as children in a post-war Naples dominated by organized crime and an oppressive family culture from which both strive to break free in different ways. Their struggles over decades dominate the stage for this two-part, five-hour production that left me breathless.

Women could not even vote in Italy until 1946. Lila, forbidden to continue her education, marries young and immediately chafes at being a man’s property. Lenu’s mother Immacolata (!) (ferocious Mary Jo Randle) is so ruled by the Church and macho codes that her daughter becomes a “whore” to her when she breaks free from a stifling marriage. There’s even a gay/ trans sibling (Colin Ryan) in the Carracci crime family, but this was before such deviation was even possibly tolerated.

Their lives are on a rollcoaster and there is much vengeful violence — real and imagined — portrayed. We are constantly wondering who will live and who will die, no less whether they will thrive.

Despite 42 characters played by 24 actors, I didn’t need to read the synopsis to follow and get totally caught up in a two-hour, 45-minute saga to rival “The Godfather” with a focus on Italian women in the decades that feminism blossomed despite the rocky soil.

The Royal Court has Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s provocative new “A Kind of People” (to Jan. 18), directed by Michael Buffong, opening on a nicely diverse group of friends, mostly in their late 30s, enjoying themselves at the flat of Gary (Richie Campbell) and Nicky (Claire-Louise Cordwell), both actors in top form. That Gary is Black and Nicky is white seems irrelevant until Gary’s boss Victoria drunkenly intrudes and upchucks a few stupid, racist remarks. From there, the drama spins out of control like a Greek tragedy, with some comic relief and some complications from the able supporting players such as Petra Letang as Gary’s sassy sister Karen.

This isn’t about “snowflakes.” It’s about what happens when a person of color can’t keep up the illusion that we live in a “post-racial” society. It’s a heartbreaking tale — the kind that is not going to go away until we all deal more honestly with race.

A new gem from out Mike Bartlett (“King Charles III,” “Cock”) at the Kiln Theatre (the old Tricycle) is called “Snowflake” (to Jan. 25), directed by Clare Lizzimore. A widowed father, Andy (Elliot Levey), and his 20-year old daughter Maya (Ellen Robertson) have evidently had a massive falling out over Brexit (or was it?) and haven’t spoken for several years. For the whole first act, Andy tries explaining all this in a monologue in a village hall where he anxiously awaits a possible meeting if not reconciliation. Young Natalie (Amber James), who is neither his daughter nor known to him, pops in and they remonstrate for much of act two about Andy’s predicament. It’s all about whether we can we talk — and whether we can we listen — in societies with a common language but few agreed upon values or even facts. Timely to say the least. Who, after all, is the snowflake?

Boomers protested the war and started the sexual revolution yet can long for a yesteryear that never was. You’d think it would make us more open to the innovations of the Millennials. You’d be wrong.

Marvelous performances from all. No easy answers.

Richard III thought the answers were easy: kill all who stand in your way. “Teenage Dick” (to Feb. 1) by Mike Lew, helmed by the Donmar’s artistic director Michael Longhurst, takes that plot to the cutthroat Roseland High election for class president where disabled student Richard Gloucester (Daniel Monks) takes on the impossibly handsome and vain football captain, Eddie Ivy (Callum Adams), and the perky but stressed devout Christian, Clarissa Duke (Alice Hewkin). Richard is egged on by teacher Elizabeth York (Susan Wokoma), woos the unattainable Anne Margaret (Siena Kelly) for political purposes, and is both assisted and thwarted by wheelchair-bound Buck Buckingham (Ruth Madeley) who has a wheel in multiple camps.

There are reminders of “Clueless” and “The Politician” in this witty and wholly satisfying send-up of Shakespeare that I missed at its premiere at New York’s Public last year but that promises to enter the high school and college theater canon and deserves to be seen everywhere.

Monks’ performance is nothing short of amazing — not because he is disabled but because he seamlessly morphs from endearing to scary to mean to hilarious without breaking a sweat (much like that other Richard). Richard’s dance scene with Anne is worth the price of admission.

“The Ocean at the End of the Lane” (to Jan. 25) is an adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s novel by Joel Horwood at the National’s Dorfman directed by Katy Rudd. A 12-year old boy (Samuel Blenkin, called “Boy”), coping with a distracted divorced dad (Justin Salinger) who has employed a woman (Pippa Nixon) whom Boy sees as a harridan, enters a world of magical realism just down the lane at an ancient farmhouse inhabited by… well, that’s not quite clear.

He befriends a resourceful girl, Lettie (Marli Siu), her no-nonsense mother (Carlyss Peer), and her wise and powerful granny (Josie Walker). What is imagined? What’s real? They all team up to fight off fearsome creatures that are the stuff of nightmares. Dark and mythic — with inflections of irony and humor — this “holiday” tale is no break from the cruelty in the world, but was embraced by audience members of all ages.

Gaiman wrote the story to

help his wife understand his childhood. You won’t be able to sit through it without some of your own buried memories floating to the surface. The imaginative staging by Fly Davis doesn’t reach the heights of the “Harry Potter” theater adaptation, but creates palpable monsters and ocean waves in an intimate house.

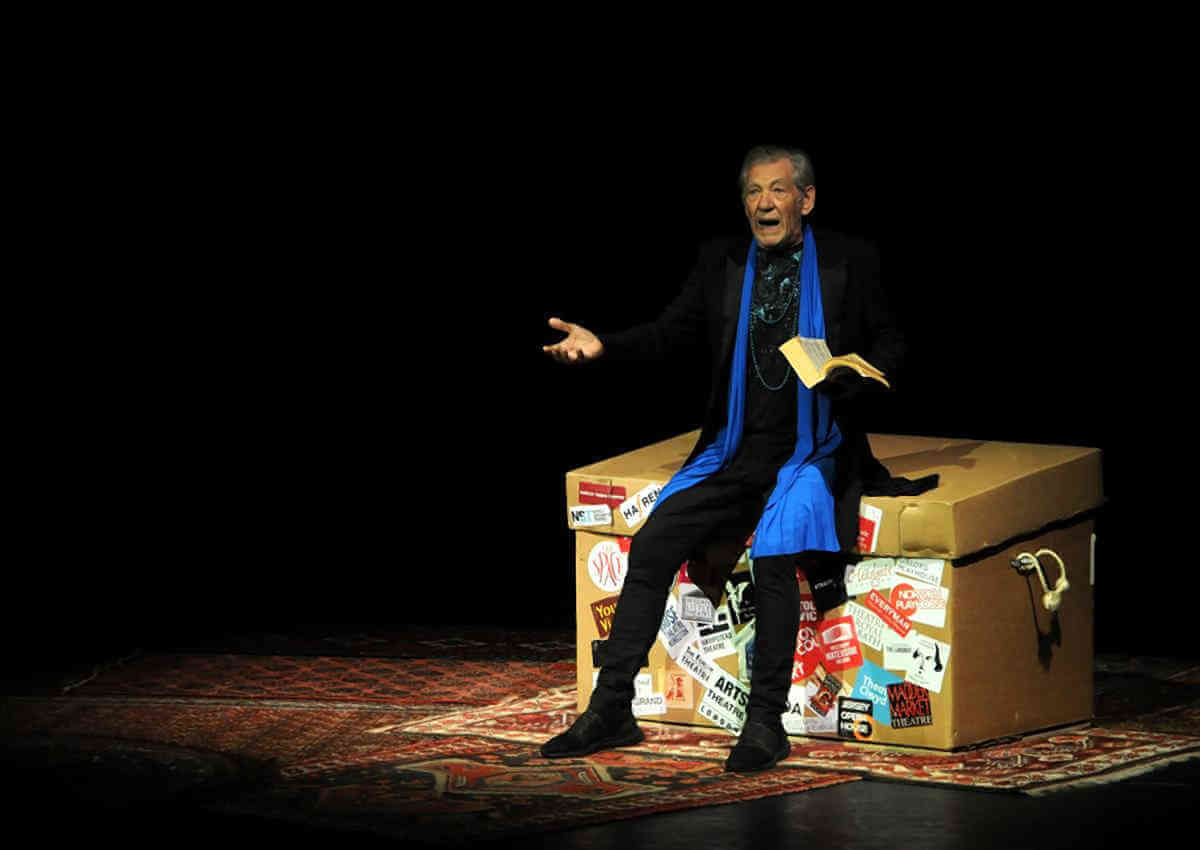

I finished my trip with “Ian McKellen on Stage” at the Pinter Theatre (to Jan. 5), the end of the great actor’s year-long world tour celebrating his 80th birthday. He holds court for three hours taking us through his life, activism, and work on stage and in film.

McKellen starts by seducing his new fans with a reading from Tolkien and stories about doing those “Lord of the Rings” movies. He treats us to some poetry by (gay) Gerard Manley Hopkins. He talks about leaving the original company of the National Theatre because there were just too many stars there 50 years ago when Laurence Olivier started it. He tells us how he came to acting and how he came out with a bang at age 47 to oppose Margaret Thatcher’s infamous Clause 28 banning any mention of homosexuality in schools.

But for most all of the second act, he lets audience members shout out Shakespeare titles and he has a story to tell about virtually all — most of which he has been in. He effortlessly delivers speeches from Shakespeare that have never left him.

But what impressed me most that the whole run has been to aid charities for young and old and that after his epic performance he runs out to the lobby to collect more donations for them and to engage close-up with his audience. McKellen is a mensch — and an international treasure.

COMING UP: “Uncle Vanya” at the Harold Pinter (Jan. 14 – May 2) with Toby Jones in new adaptation by Conor McPherson; Tom Stoppard’s new “Leopoldstadt” at Wyndham’s (Jan. 25 – Jun. 13); Alan Cumming and Daniel Radcliffe in Beckett’s “Endgame” at The Old Vic (from Jan. 27); Lesley Manville in Dürrenmatt’s “The Visit” adapted by Tony Kushner at the National’s Olivier (Jan. 31 – May 13); Rafe Spall in “Death of England” at National’s Dorfman (Jan. 31 – Mar. 7); Jessica Chastain in “A Doll’s House” at the Playhouse (Jun. 10 – Sep. 5); Whoopi Goldberg and Jennifer Saunders in “Sister Act” at the Eventim Apollo (Jul. 29 – Aug. 30); Imelda Staunton in “Hello Dolly” at the Adelphi (from Aug. 11).