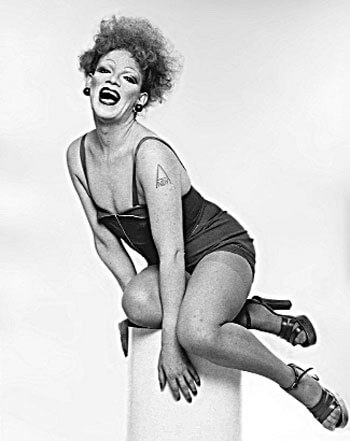

Jackie Curtis doc recalls a 70s downtown that defied even Stonewall’s expectations

And then there was the time that Jackie turned up at a Busby Berkeley audition for the Broadway revival of “No, No, Nanette” in a battered U.S. Army jacket—and a turban made of torn stockings.

And then there was the time she ripped up an old housedress and put it on.

“What are you doing?” someone asked.

“It’s a look, isn’t it?” Jackie replied.

And then there was the time a 90-year-old Lower East Side lady in the next apartment died. Next thing you know, Jackie was sidling along the ledge between her apartment and the neighbor’s to go in her window and steal her clothes. Curtis later neglected to launder them.

And then there was the time at Max’s Kansas City when somebody said: “Hey, are you a real woman?” and Jackie snapped back: “Do you think a real woman would dress like this?”

“One thing that was delightful,” says Lily Tomlin in her narration for “Superstar in a Housedress,” Craig B. Highberger’s 95-minute all-hands memoir about 1970s off-off-offbeat playwright/poet/actor/director/personality Jackie Curtis, “was that you never knew how Jackie was going to show up… He might be dressed as a woman or as a man. You never thought twice about it. You sort of envied someone who was able to casually cross that barrier back and forth . . . ”

“It was just original,” Tomlin continues, “that exaggerated look. He made us see the absurdity of the culture.”

“I am not a boy,” said Jackie. “I am not a girl. I am not gay, not straight. I am not a drag queen, not a transsexual. I am just me, Jackie, playwright and poet from the Lower East Side of Manhattan.”

Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis was in fact born in New York City on February 19, 1947, and her name at birth was John Holder, Jr. John Holder Sr. soon thereafter split. Jackie’s mother and grandmother had been Depression-era taxi dancers—the same grandmother, proprietor of Slugger Ann’s bar, with whom Jackie lived, over the bar, while he was growing up.

One of the 30 people who come before the camera in Highberger’s absorbing, many-faceted portrait is Jackie’s half-brother, Tennessee-raised Timothy Holder, a gay Episcopal priest in the Bronx. As kids, Jackie and Tim used to summer together in Tennessee.

It was at Ellen Stewart’s La MaMa E.T.C. that Jackie Curtis at 17 first went on stage, opposite Bette Midler, in Tom Eyen’s “Miss Nefertiti Regrets,” and it is Ellen herself, Jackie’s other mother, who now says: “He lived with his grandmother and was a wonderful writer and when he transformed himself he became one of the most beautiful women I’d ever seen.”

But not a little woman. Somebody in the movie—maybe it’s John Vaccaro—speaks of Jackie, at 6-foot-2, with the body of a linebacker, as hardly being a delicate creature. More than one witness recalls Jackie’s poor hygiene and body sweats.

“I don’t know what went on in his mind when he would go outside unshaven, wearing lipstick,” says Harvey Fierstein, who in 1972 played Jackie’s mother in her “Americka Cleopatra.” In that epic, the playwright played a sleeping princess who refused to stay asleep.

“I’d hit him with my purse to make him lie down again,” says Fierstein who also remembers Jackie tossing his Barbra Streisand wig over a light bulb, where it melts.

“Americka Cleopatra” followed by five years Jackie’s “Glamour, Glory, and Gold,” starring Candy Darling and a young unknown named Robert De Niro. In 1971, Ellen Stewart supported six months of rehearsal for Jackie’s chez d’oeuvre, “Vain Victory,” during the preparations for which the cops came in on a fake bomb threat, to purposefully delay the opening, searching everyone’s tutus for drugs.

Those were the days. On the one hand, one was inspired to make costumes out of discards from fabric houses and sets from junk from the street “like Louise Nevelson does.” On the other, one Warhol stalwart, Taylor Meade, dyspeptically puts down people from the period for appearing “in the most tasteless drag, looking like they’re wearing carpets.”

It is a story full of ironies, not least when, of all people, radio’s amiable longtime interlocutor Joe Franklin turns out to have been a friend and admirer of Jackie Curtis from way back; or when, in 1969, less than a month after Stonewall, the wedding of Jackie Curtis to Eric Emerson takes place on a rooftop, except that Eric Emerson doesn’t show up; or when, at the end, on May 15, 1985, Jackie is dying of an overdose and the woman with him, instead of calling 911, thinks she can bring him out of it by giving him a blow job.

“So,” says Fierstein, “Jackie has his probably first heterosexual experience at the moment he’s dying.”

There is one overarching irony. Half the people in the film speak of Jackie Curtis as “him” and half speak of Jackie Curtis as “her.” It switches constantly back and forth. But that isn’t an irony, is it? It’s the truth.

Sort of. Because at the very end, before they put Jackie into the ground on a hillside in Putnam Valley, coating the grave with rhinestones and red glitter visible from a half-mile away, we see him for just a moment in his casket, lying there in a black suit, neat and clean. He doesn’t look like a girl. He looks like a big, dead, raw-boned, square-jawed jock.