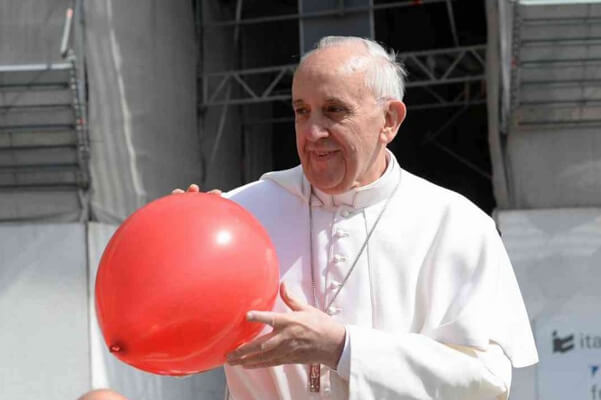

Pope Benedict XVI is leaving defeated, with the Catholic Church’s problems unresolved.

Bracketing the Pope’s retirement were votes approving marriage equality in France and Great Britain. The rejection of the Church’s teaching, said the Tablet, a British Catholic newspaper, “undermined [its] authority” in the global dialogue on gay rights. Staunchly defending traditional moral understanding hasn’t made the Church more influential.

“The mainstream religious bodies, including the Catholic Church and the Church of England, campaigned against the bill, avoiding the obvious pitfalls, but won few converts to their cause,” the Tablet concluded in an editorial. Both Churches said “what they felt without weighing the consequences,” the editorial continued, before warning, “The consequences have now to be lived with.” With Britain’s Parliament rejecting a fundamental moral teaching, “the authority of that teaching in the future” has been weakened.

These are words to ponder for anyone thinking traditionalist dogma can be preserved without modification. Clinging to rigid views doesn’t solve problems, it amplifies them.

The pope’s dogmatic faith — developed over decades of work as his predecessor’s doctrinal watchdog — caused serious missteps in his own tenure. Even as he threatened heterodox thinkers with excommunication, he could not bring the weight of the Church squarely to bear in holding priests who raped children accountable. The cruelty and absurdity of making wrong thinking a more serious offense than a priest forcing himself on the most vulnerable in his flock exacerbated the moral and public relations disasters of the sexual abuse scandal. The Church repeatedly dodged its responsibilities to reconcile with victims as their complaints spread across the world to Ireland, Mexico, and Australia.

What heightened the disarray is that the scandals often involved Benedict’s ideological soul mates.

A wise administrator would turn abusive priests over to the police, satisfying the victims and creating a standard operating procedure to demonstrate the old ways had ended. This sensible approach proved beyond the power of this pope. By insisting on secrecy time after time after time, the Church writ large became a target.

Last year, a Kansas City bishop was convicted of a misdemeanor offense for failing to report child sex abuse. Robert W. Finn, who was vocal in his support for Opus Dei, a notoriously secretive archconservative Catholic group with close ties to Benedict, was sentenced to probation for failing to pass along information the diocese had about Father Shawn Ratigan’s collection of hundreds of pornographic pictures he had taken of young girls in his charge. The story only surfaced when a computer repair shop undertook the duties that Finn had failed to perform and notified authorities.

In Australia, the Church’s sex abuse scandal has reached historic proportions, A Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse has been convened, and its targets of investigation include the Catholic Church. The Conversation, an Australian journal, reported that the commission’s purpose is to “focus on cases of institutional sexual abuse and not on cases of sexual abuse within the family.” The Church’s failure to get ahead of the scandal but rather to be dragged into it by government special panels is a damning indictment of the pope’s leadership.

Credible reports — buffered by Benedict’s own words that “I’m resigning for the good of the Church” — suggest he agreed with this conclusion. How other pressures — such as the detailed recounting the pope recieved late last year about gay sex parties among Vatican insiders, which the Italian newspaper La Republicca reported about last week — contributed to his decision may be harder to sort out.

Catholics in the Western democracies have voiced their unhappiness by asking that the Church “modernize.” But few seriously believe it is yet prepared to get out of its straitjacket. Modernizing means ending celibacy, providing constructive advice to the Church faithful on sexual matters, including the use of condoms, and acknowledging that an absolute prohibition against abortion means endangering the well-being of some pregnant women. American Catholics apparently don’t accept the argument that abortion is murder, but the Church remains obdurate.

A majority of Catholics vote Democratic and have social views more liberal than society as a whole, but the hierarchy has joined an alliance with Republican evangelical Christians. The Catholic laity is often pro-choice, believes in the individual’s right to choose their own sexuality, including their priests, and supports the equality of women and their right to ordination. As important, they believe that doctrine improves with open debate.

Still, most also expect the Church to act like Napoleon and plunge deeper into Russia without contemplating the costs. Modernizing is the only solution, but the Church sees it as a retreat. This mindset will prevent Catholic religious leaders from recognizing any opportunity for a new dawn.