Tony Shalhoub’s directorial debut examines a family in crisis

Beauty is only skin-deep. Oh yeah? Not to teenaged Sara Tivey, who looks on college as a waste of time and money, whose mind is instead set on becoming a cosmetologist––in plainer language, a beautician. As Sara sees it, beauty is all. Well, maybe not all, but it helps, and it could certainly help her mother.

“I was prepared for everything,” says Elizabeth James Tivey, the brisk, intelligent woman who gave up an acting career to become Duncan Tivey’s wife and Sara’s mother. “A heroine addict, a nymphomaniac––but a cosmetologist?”

Sara (Eva Amurri) flares up: “You think only poor, uneducated women can be cosmetologists?”

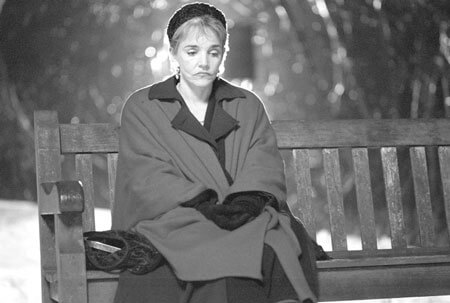

She wants to give mama a makeover––to re-beautify the basically handsome Elizabeth (stunningly handsome Brooke Adams) who let her hair and her expectations go gray after Duncan (Gary Sinise), long into the marriage, ditched Liz for a bosomy blonde young cupcake.

This is the premise, the starting point, of “Made-Up,” a subtle, many-layered motion picture that, in its opening at the Angelika, marks the directing debut of actor Tony Shalhoub, Brooke Adams’ husband, and has a screenplay by actress Lynne Adams, Brooke Adams’ sister. Lynne Adams not only wrote it, she’s in it––as Kate James, concerned sister of Elizabeth James Tivey.

Kate is a documentary filmmaker. Her current project, with camera and crew invading the house and everyone’s privacy, is to shoot a film documenting all the twists and turns, emotional and otherwise, of young Sara’s makeover of Elizabeth, starting with the black sexy-golliwog Elizabeth Taylor wig that has Elizabeth James Tivey saying, as she confronts herself in it in a mirror: “I look like I’m in drag.”

To her daughter, Elizabeth says, “Sweetie, I know you have the idea that if Dad sees me like this, we’ll get back together.” Then, to the mirror: “Holy shit! What if she’s right, and we do get back together again?” And then, waving a cautionary finger at camera and Kate in an instantaneous jump from one level of “reality” to another as “Made-Up” does throughout: “I don’t want Sara to hear any of this.”

“Mom!” Sara has protested. “All I want is for him [the errant papa] to pay for cosmetological school.” The girl will a moment later confess to herself (and the camera): “It’s hard for me to be mad at him, I don’t know why. So what if he fucked Molly once?” Ah, innocence. Ah, willful delusion.

Molly (Light Eternity) is that bosomy blonde cupcake, an artist of sorts who tries to shore up her female-sisterhood credentials with “my father left my mother too,” along with the staggering observation that “Just because a man has money, he can leave someone like Elizabeth for someone like me.”

For all that, Molly is now worried that Duncan is getting turned on once more by Elizabeth. Not the wigged, face-made-over new Elizabeth who goes by the name Betsy. The other old one, the real one. “I love the silver hair!” Duncan has announced. That Gary Sinise looks about 12 years old saying this is another part of the Pirandello effect.

Wheels within wheels, layers within layers. Tony Shalhoub, the reel’s real director, pops up as Max, a bearded and amiable restaurateur whom unreal director (but real screenwriter) Kate/Lynne fingers as the next beau for Betsy. The complicated setup gets even more so when Max arrives unexpectedly and is let in by Betsy’s gray-haired sister, the real Elizabeth. “Oh my God,” says theater-buff Max, “I just realized. That’s Elizabeth James, the actress.”

For a moment he considers playing the cad and going after both sisters. “But then I remembered that Elizabeth and Betsy are the same person. That’s how good an actress she is.”

It’s an opinion shared by Elizabeth. “I feel fat and old and ugly and way past this pretentious [dating] crap,” she says to Kate. “I never could do this, even when I was young. The only way was when I was drunk.” So Kate slips “Betsy” some vodka in preparation for the big front door clinch with Max. Betsy/Elizabeth, sans wig, gets sloshed and obstreperous, ending in cartwheels. The next day she exclaims to Kate: “You thought I was really drunk? I am good.”

An incidental but key character in “Made-Up” is a young man named Chris (Kalen Conover), a freaky, bleach blond NYU-type film student who’s along for the ride on this shoot, and who keeps saying things like: “If this is going to be a documentary at all, it will be about the making of a movie, and not some ‘Blair Witch’ crap.” Dourly, he also remarks: “Everyone wants to be real. Like, it’s hard to be real.”

Well, “Made-Up” may be much more real-within-real-within-real than anything ‘The Blair Witch Project’ dreamed to be. But if it’s of a different genetic order than “Blair Witch,” it does have another and very clear antecedent: the 1973 PBS television series “An American Family,” in which the Louds of Santa Barbara, California, opened themselves up to an invading film crew and the world’s scrutiny of everything from wife Pat Loud calling husband Bill Loud a horse’s ass, on camera, to teenager Lance Loud’s open and unapologetic homosexuality and the ditsy-ness of his several siblings.

That was reality TV before reality TV was invented. “Made-Up” is reality moviemaking of a different and somewhat more complex order. Consider just the title, which has at least four possible umbrella meanings:

Made-up in the cosmetic sense, what Sara does to and for her mother.

Made-up as reconciliation, or possible reconciliation, between Elizabeth and Duncan, Sara’s parents.

Made-up as make-up-for––more exactly, in words scriptwriter Lynne Adams has put into filmmaker Kate’s (i.e., her own) mouth: “To make women feel good about themselves.”

Made-up as, well, made up––i.e., fiction. Let’s make up a story. And we’ll all be in it. If it is any good, who’d dare call it nepotism?

Not this viewer. It is indeed quite good enough to keep you puzzling —and thinking.