David Leveaux stages “Fiddler on the Roof” with too many punches pulled

The new staging of “Fiddler on the Roof” is nothing if not the most sumptuous production of the show I have ever seen.

Even if the set by Tom Pye is somewhat generic––it could serve any number of Shakespeare or Chekhov productions––it is lush. The lighting by Brian MacDevitt is rich, and Vicki Mortimer’s costumes are very nearly a textbook example of how to use fabrics and textures to convey character.

Unfortunately, the production is not much more than visually sumptuous.

Under David Leveaux’s surprisingly lackluster direction (his “Nine” last season was brilliant), the entire production takes on a kind of gauzy sentimentalism that sucks the life out of the world of Anatevka, the early 20th century Russian village that is the setting for the play. This is a “Fiddler” that seems to have been mounted to capitalize on romanticized memories of a classic American musical, rather than re-imagining it for a contemporary audience.

This is truly a disservice, for in taking the theatrical equivalent of a belt sander to the dramatic edges of the show, Leveaux delivers a cool and distant “Fiddler” that is neat and tidy and runs no risk of offending anyone. Perhaps in this cautiousness, this truly is a “Fiddler” for our time; it is virtually impossible to take issue with this show and its themes as they are presented here.

But what a missed opportunity. In a climate in which Mel Gibson is promulgating a vision of Christianity through his quasi-liturgical snuff movie, and rampant religiosity is invoked at every turn, we need a vital Tevye to offset the stridency and bring faith back to a human scale.

To me, the dramatic tension of “Fiddler” has always been between Tevye and God. Tevye is a proud man of strong faith, steeped in tradition, who is forced to reexamine himself, his life, and his beliefs as the world is changing around him. There is a particular poignancy in this as the story is set in 1905, just at the time that the pace of cultural change began to accelerate in ways that take Tevye by surprise. Nothing in his life––that has found such comfort in tradition––has prepared him for the world he is encountering and he is frightened and unprepared. So, he turns to God, as he and his ancestors have always done.

Yet what makes Tevye so appealing is that his is neither a blind nor a messianic faith but one that is deeply human and tirelessly questioning. Tevye’s struggle is not to impose his will on God, or even his interpretation of God on his family, but to find just enough understanding to go on one more day. One of the reasons that “Fiddler” has endured for 40 years is that despite its setting and the metaphor of Judaism, the ongoing struggle to understand ourselves in relationship to our faith in a dynamic world is a unifying human quest. If one has the theological chops to eschew the dogmatic imposition of one’s own ego on God, the result can be a life lived in the wonder of faith.

But what a lot to put on a little musical. Yet, I think it’s valid, and it’s all there in the script, punctuated by Tevye’s conversations with God and in the brilliant score. Musically, the square, predictable yet rich structure of “Tradition” gives way to looser, more contemporary rhythms and harmonies as the world changes, culminating in “Anatevka,” which counterpoises the rigidity of “Tradition” against an unsettling rhythm that perfectly exemplifies the fear that mixes with faith in trying to hold onto one’s roots while entering a new world.

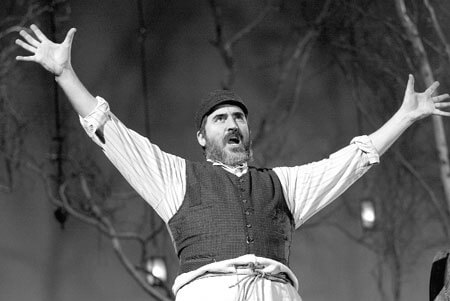

The reason this “Fiddler” doesn’t work as well as it could is that this substance appears unaddressed. Alfred Molina as Tevye is a pushover in his relationship to God. He is charming enough, but he is consistently bland and pleasing in his public life and his private wrangling with the Almighty. Molina never finds the dramatic arc of the character, so that when the final piece falls and he is able to bless Chava despite the fact that she has married outside her faith, we should feel his surrender to that which he cannot control. Instead, we have a moment in which the daughter gets her way. Dramatically, it should be Tevye’s moment, not Chava’s. Leveaux gives the scene a contemporary spin by focusing on the willful daughter.

Similarly, during “Matchmaker,” the daughters run around, take their clothes off, and exude a knowledge of their own sexuality inconceivable in the world of 1905. These girls surely have sexual longings, but by tipping his hand so early in the show, Leveaux robs us of the discovery that each of the three older daughters makes as her heart opens and Tevye takes the radical step of abandoning tradition so each can be happy in ways he never allowed himself to entertain. Without taking this dramatic journey, the song “Do You Love Me?” in the second act loses its integrity and becomes the bickering of two old married people, rather than a beautiful moment that shows that even within the constraints of tradition, it was possible to create love.

The cast is for the most part fine. Randy Graff is very good as Golde, but Nancy Opel tends to overplay the matchmaker Yentl, making her a cartoon. I’ve never seen a professional production of “Fiddler” in which Yentl did not get exit applause on her first scene, but when Leveaux seems flummoxed by a character, he just lets the actor do whatever he or she wants, thereby losing the moment. That certainly is the case with the tailor Motel. John Cariani plays the part like a hyperactive six-year-old whose Ritalin has worn off. Why Tzeitel, underplayed by Sally Murphy, would want him is a mystery. Laura Michelle Kelly is wonderful as Hodel, and Robert Petkoff as Perchik gives the best performance in the show, integrated passionate, and real. The disparity among the performances indicates that Leveaux was busy doing something else as these characters evolved.

From the pogrom that sounds like the dropping of a bunch of dinner plates to a Tevye who is a pushover, this production never offends, but it never catches fire either. Certainly it’s risky to offend, but it’s irresponsible and unfulfilling simply to decorate around the drama. If you’re going to do “Fiddler”–– and given the traditions that are causing great strife in our culture, this is a perfect time for it––do it fully and unapologetically. The theater and the cultural dialogue will be stronger for it.