As local, state, and federal governments grapple with reforming policing in the wake of global protests responding to four Minneapolis police officers killing George Floyd, an African-American man, police unions are commonly seen as a significant obstacle to changing that profession. But little attention is paid to the culture in police departments that may reinforce racist biases and ignore or perhaps even reward some forms of misconduct.

“The NYPD has a troubling practice of failing to meaningfully discipline their officers for misconduct,” Molly Griffard, an Equal Justice Works Fellow at the Legal Aid Society, said in a statement. “The practice is so widespread that it has created a culture of impunity and signals to officers that they will not be punished for egregious behavior such as brutalizing civilians, lying on the witness stand, planting evidence, or making retaliatory false arrests.”

Legal Aid has compiled police disciplinary and misconduct records first published by Buzzfeed in 2018, data from open records requests and from New York City’s Open Data Portal, and records from federal lawsuits in its Cop Accountability Project, or CAPstat, database. The records represent just a few years of data, but they show that when uniformed NYPD employees from police officers to senior leadership are accused of serious misconduct or named in civil rights lawsuits, if they suffer consequences, they are limited.

Roughing up civilians once helped a cop’s career; de Blasio, some experts say that’s changed

Attorneys who represent plaintiffs in civil rights cases against the NYPD and the city point to one recent example.

In 2014, Terence Monahan, now the chief of department and the highest ranking uniformed police official, was assessed $25,000 in punitive damages for his conduct in arresting four people during the 2004 Republican Party Convention in New York City. Punitive damages are intended for particularly egregious conduct and are meant to punish a defendant.

“He was personally involved in a number of mass arrests that he himself ordered,” said Jeffrey Rothman, an attorney who represented multiple defendants in what came to be called the RNC cases. “It didn’t hold him up.”

Monahan was an assistant chief in 2014. He was promoted to chief of patrol in 2016 and won his current position in 2018. The NYPD did not respond to an email seeking comment, but Mayor Bill de Blasio defended Monahan during a June 23 press conference.

“I don’t know the details of that, but I do know Terry Monahan really, really well,” the mayor said. “He has been one of the chief agents of reform in recent years in the NYPD in terms of moving it from a punitive entity in the sense of heavy emphasis on arrests and stops to a police force that has consistently not only used a lot fewer stops, used a hell of a lot fewer arrests.”

Among the strategies the de Blasio administration has used for police reform is to reduce the opportunities for police-public interaction. That has meant reducing stop and frisk from nearly 700,000 stops in 2011 under Mayor Michael Bloomberg to 13,459 in 2019. Arrests have been reduced by 180,000 in 2019 compared to 2013, Bloomberg’s last year in office.

If there has been change in the NYPD’s culture, history suggests that change is recent.

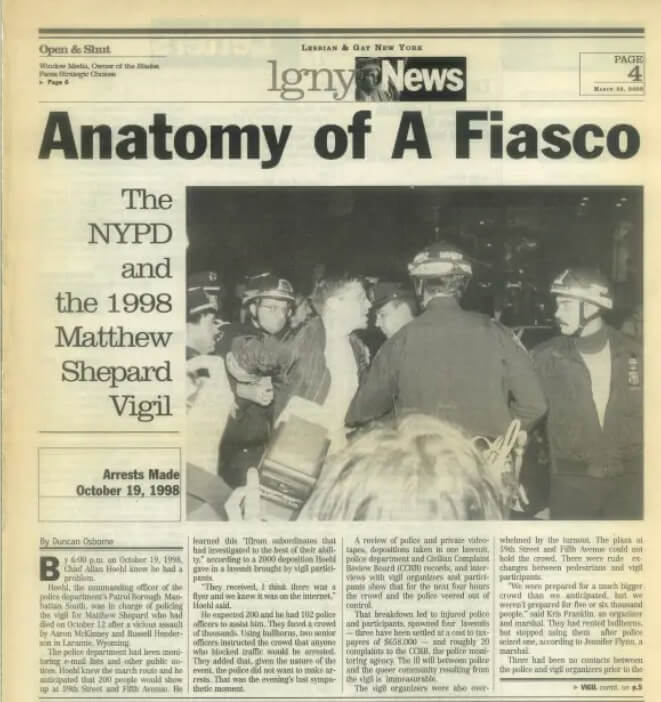

In 1998, Thomas Graham was the deputy inspector running the department’s Disorder Control Unit. When a vigil for Matthew Shepard, a 21-year-old college student who was murdered in Wyoming, drew thousands of marchers who were to march on Fifth Avenue from 59th Street to Madison Square Park, police first tried to stop the vigil altogether then blocked marchers who moved to Sixth Avenue and continued heading downtown. Eventually, hundreds of marchers were penned on West 43rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues with a Graham subordinate, Captain Ronald Shindel, and a group of officers holding a line west of the march with another line to the east. Graham then instructed a group of officers on horseback to do something. It was never clear what that instruction was. What they did was charge into the crowd seriously injuring three people.

Graham joined the NYPD in 1973. By 1981, he was a sergeant and would have made lieutenant sooner than 1986 had he not led a group of officers into Blues Bar, a Manhattan business that served a predominantly transgender clientele, in 1982 where they wrecked the bar, threatened customers with violence, and used anti-gay and racist slurs because they blamed clients there for an assault on two detectives. Graham retired in 2010. He had been promoted to deputy chief when he left.

Shindel joined the NYPD in 1982. In a 2000 deposition taken as part of the Shepard vigil lawsuits, he said he had “in excess of 20 civilian complaints” and “numerous” investigations by the NYPD’s Internal Affairs Bureau. Shindel had been promoted to deputy inspector when he left the NYPD in 2002. In 2013, he was hired by the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD) as a captain and was promoted to deputy inspector in 2015. The PAPD is part of the MTA, which is a state agency that is not under the control of New York City government.

Former NYPD detective Tom Verni, who is gay, said he encountered “older guys left from the ‘60s” who were “all about kicking ass and taking names” when he joined the NYPD in 1992. He left in 2013 and a culture that had once accepted or even approved of misconduct had changed.

“The training has been vastly improved,” Verni said. “The command staff in every precinct and every unit just doesn’t tolerate that kind of behavior.”

Stephen Bishopp, a sergeant in the Dallas Police Department who has a Ph.D. in criminology from the University of Texas at Dallas and has authored or co-authored several studies on policing, said that police who “use more force than necessary or have anger-issues” tend to be less successful in their careers.

“Such a thing doesn’t help a career and I have not seen any research in the last decade that suggests otherwise,” Bishopp wrote in an email. “In my own experience, it negatively affects the officers, particularly if the complaint against them is upheld or sustained.”

Bishopp said that the “wrong kind of aggressive” may have been seen among police “to some extent 30+ years ago” noting that his father may have one of those officers.

“My dad retired as a police chief having started his policing career circa 1975,” he wrote. “He was certainly known for being this kind of officer but it was viewed positively back then.”

Dr. Maria Haberfeld, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and director of the NYPD Police Studies Program, has authored or co-authored multiple books and peer-reviewed journal articles on policing. Haberfeld was definitive.

“In many departments, including the NYPD, it will actually prevent you or slow down your promotion opportunities,” Haberfeld wrote in an email. “I cannot speak for the entire history of NYPD, but certainly this is not the case in the past few decades.”

While the mayor said that his reforms had altered the NYPD’s culture, his view was that work was not yet done. He pointed to the swift action take against an officer caught in video using a chokehold, which has been banned by the NYPD for over 20 years, on an arrestee on June 21. That officer was suspended “within hours” and his disciplinary process had begun, the mayor said.

“It proves that change can come, but we need a lot more change,” he said. “One of the things we’re going to be working on going forward is making sure there’s a much better mechanism for weeding out the cops who should not be on the force and for bringing up a leadership from the grassroots that represents all New York City and represents a more reform minded view of policing because we have to break what’s still wrong in that culture.”

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.