With “Six Feet Under,” HBO queers American family values

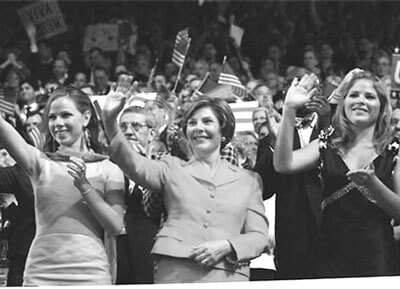

Family values are not new to presidential politics or to television, but this year’s Republican National Convention transformed America’s first family into the latest TV reality show. George W. Bush stars as Dad-in-Chief with his devoted wife, photogenic twins, and proud parents in supporting roles.

In a multimedia production that persisted for four days, three generations of the Bush family told anecdotes, shared personal humor and modeled affectionate behavior for millions of television viewers. The spectacle’s expert packaging reduced family life to conservative slogans and “Leave it to Beaver” photo-ops.

Another celebrated television event, a week later, also focused on the family, but HBO’s finale of the forth season of “Six Feet Under,” spoke to a different truth. Alan Ball’s hit drama about undertakers questions the static notion of family values put forth in political myth in its brash depiction of complex and sexually diverse family dynamics.

Though the show’s first family seems traditional––the Fishers go to church, operate a small funeral business, and eat breakfast together––the show explores this modern family in a deep and intricate way, challenging the one-size-fits-all model over which Barbara and George H.W. Bush are currently the symbolic cultural caretakers.

“Six Feet Under” focuses particular attention on how sexual identity is expressed by queer characters in a typically dysfunctional family. This past season, David Fisher (Michael C. Hall) and his long-term partner Keith Charles (Matthew St. Patrick) traded in an open relationship for monogamy.

“We basically are married even if the law doesn’t recognize it,” Keith says. And David says that they’ve had preliminary conversations about adoption. But when David is threatened with a lawsuit, the couple agree to an indecent proposal offered by the male plaintiff who finds Keith a perfect match for his sexual fantasies about black cops. Keith allows the man to perform oral sex on him to protect his lover. Gay sexuality, in this case, does not threaten the family, but instead defends it, even if in a way that demonstrates David and Keith’s nontraditional ethics about sexuality. Their relationship is actively queer in that it continually challenges relationship norms.

In another episode, Keith queers his gay identity by allowing the pop diva for whom he works as a bodyguard to seduce him, even after turning down the sexual advances of a very hot, bi-curious male co-worker. For David, it is this dabble at heterosexuality that threatens the family.

Not all of the queer family values play out with the show’s gay characters. As the season progresses, Brenda Chenowith (Rachel Griffiths), amidst a mildly S/M relationship with a neighbor in which she is the dominatrix, hooks back up with Nate Fisher (Peter Krause). Nate, who is having difficulty getting over the death of his wife Lisa as he cares for their daughter, initially tells Brenda he is reluctant to father a child with her, that he wants it to be “just the three of us.” Brenda herself comes from a family with unstable sexual boundaries and is recovering from a sex addiction. This makes the prospect of having a family a dangerous one, a persistent “Six Feet Under” theme.

The season finale resolved Nate’s agony over Lisa’s death––giving him the confidence to seek a family with Rachel–– but only at the cost of a tragic suicide by another family member who whose motivation to murder had been his betrayal of the family.

Elsewhere, family unity also came under pressure.

Rico Diaz (Freddy Rodriguez), co-owner of the funeral home, engages in a sexual dalliance more familiar to television– –adultery. Married to Vanessa Diaz (Justina Machado) and with two children, Rico’s involvement with an exotic dancer was always more about companionship than lust––the two never even had sex until Vanessa found out about the time they were spending together and threw Rico out. In the final episode, Rico apologizes and asks for forgiveness, but Vanessa says she wants a divorce.

“Being close to someone else when you’re the most important person in my life,” Rico finally concedes. “Yes, that was adultery.”

Rico’s sexuality is far tamer than David’s, Keith’s, Nate’s or Brenda’s, but his transgression against Vanessa is far deeper than any hurt caused by members of the other two couples.

“Six Feet Under” is more interested in issues of intimacy and trust than in sexual acts. Family bonds are created and sustained by emotional support, separate from the sex and the desire to have children.

As always, the family struggles on “Six Feet Under” this season played out against the backdrop of death. The show’s setting in a funeral home enables it to televise death in a candid and realistic way that has earned it critical praise. Perhaps it is this unflinching look at life and death that facilitates such a such a sophisticated and nuanced discussion of sexuality and family models. The constant confrontation with mortality carves out a space for the audience to experience the truths of family and relationships.

On many occasions, the bereaving visitors to the funeral home illuminate new perspectives about family. In the final episode, Rico consoles a woman who sits alone mourning the ex-husband she had divorced many years before and lost touch with.

“Family is family,” Rico tells her. “Divorce doesn’t change that.”

“Not divorce, not death, not anything” the woman replies. “When people get in your heart.”

“They stay for good,” Rico says tapping his heart, reaching for the woman’s hand and demonstrating his belief that family equals love.

On “Six Feet Under,” families tolerate and endure diverse sexuality, death, heartbreak, trauma, addiction, and much else that the political spins doctors tell us America doesn’t want to look at in a political campaign. So while the Bush twins read from a script oddly crafted for girls at least a half dozen years younger they are, the Fishers, the Diazes, and the Chenowiths confront a more realistic version of life and model their notions of American family values to television audiences.

We also publish: