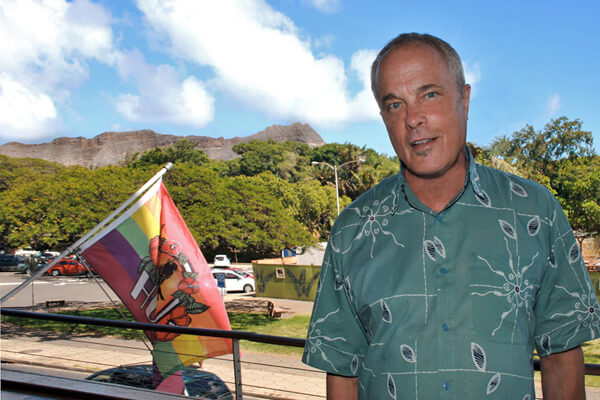

Ka’Ikena Scanlan, a 24-year-old Jawaiian singer and songwriter. | DAVID NOH

My annual sojourns to my Hawaii homeland always remind me of just how much musical talent is there, fitting, I guess, for islands once ruled by the prolific composers King Kalakaua and Queen Liliuokalani, who wrote “Aloha Oe.”

One of my Punahou School classmates, Haaheo Scanlan, has a 24-year-old son, Ka’Ikena Scanlan, who is a talented singer and songwriter. The first time I heard him sing his “He Kanaka,” I was struck not only by the majestic beauty of his young voice but also the powerful and proud message of the song, which has enjoyed considerable local success, especially in Hilo on the Big Island, where he performs frequently.

The song falls squarely in the reggae-influenced genre of Jawaiian music, hugely popular in the islands for years — even if it often left me cold. But “He Kanaka” — for probably the first time — made me fully understand and truly embrace the style.

Honolulu, threatened by global wealth’s incursions, still rich in cultural traditions

After a “mahalo” (“thank you”) for bringing up the Jawaiian genre, Scanlan said, “I actually wrote this song based on the current influence that Jamaican culture has in our Hawaiian community. Many of our Hawaiian musicians have fallen in love with the beautiful Caribbean island music called reggae and have picked up a cultural/ spiritual connection, also. As a reggae musician, I have been asked if I am a Rastafarian and if I belong to the faith. I wrote this song in hopes that I could bring awareness to the lack of authentic Hawaiian ideas in Hawaiian music these days.”

After giving props to his mother for having him study piano when he was “really young,” Scanlan said, “I would say my oldest brother Malosi had the most influence on me through music. He consistently gave me musical instruments as gifts, to instill my passion for music throughout my life. He started by taking me to drum at his capoeira classes as a very young child. Then he started buying me various instrument, like a guitar, a bass, an electric drum set, and lots of other stuff, too.”

Ka’Ikena Scanlan. |DAVID NOH

The traction “He Kanaka” has gained among Hawaiians brought Scanlan a lot of recognition and award nominations, but he said, “Any award or success through competition is nice, but, honestly, that isn’t why I chose this path, nor is it really apparent yet. The real success has come from the support and appreciation that I have received from my listeners. I know this is a message they have been waiting to say or hear but not too many people are willing to approach it. So when I hear people giving genuine appreciation, that really is the feeling I was hoping for, and I totally get it.”

He added, “I hope to be able to spread a positive message to the Hawaiian people here at home and those finding business in the States and the world. I want to bring back the pride in our Hawaiian people through leading by good example. I always loved music, so I wanted to live a life that allowed me to sing and write honestly while also teaching and growing my own food.”

Fluent in the Hawaiian language, now one of the most popular majors in local schools, Scanlan is an instructor at the University of HawaiÊ»i at Hilo. “I teach two classes, Hawaiian language and Hawaiian ethnobotany. I truly love this job and being able to spread knowledge that once was thought might become extinct.

“I was actually sent to a few different schools as a child and was considered challenged when it came to education. I take pride in the fact that I have been able to take what I have been dealt and still be able to teach at a higher learning institution.”

About “He Kanaka,” he explained it “tells of the suppression of our culture and our people during the introduction of Western colonialism. The chorus then focuses on the common misconception of a reggae musician as just a Rastafarian. I say in my lyrics that I am not a Rasta, but simply just a kanaka [Hawaiian] who lives in HawaiÊ»i nei. The next verse includes Hawaiian values like ‘Huli ka lima i lalo’ [turning our hands to the ground].”

All people in Honolulu seem to be talking about is the booming neighborhood of Kakaako, once an arid patch of warehouses and auto repair shops, where luxury high rises are springing up like weeds, terrifyingly presaging a time when, like Manhattan, Hawaii will become a playground for the international rich, with its current residents shunted to the side — or, sadly, to the continental US. I kept hearing about the flourishing art scene supposed to be burgeoning there, as well, but after two exploratory attempts, I found only a few random studios, a passel of idiots playing Pokémon, and some very fetching and well-executed Hawaiian-themed wall murals that were a relief from the hideous dolphin-dominated work of the ubiquitous Robert Wyland.

Happily, the Honolulu Museum, formerly known as the Academy of Art, remains a cultural treasure in town, housed in its exquisite stucco Bertram Goodhue edifice. There, I caught the fifth annual Hawaii Burlesque Festival and Revue, featuring New York’s Trixie Little, the reigning Queen of Burlesque and Miss Exotic World 2015. The standout performer for me, however, was Madame X, a stunning 20-year veteran Asian dance performer whom I caught last year in an Elvis Presley revue. She always dazzles me with her sparkling verve and impeccable physical line.

The Korean film festival was running, and there were two entries that addressed the brutal Japanese occupation of Korea during World War II. Lee Joon-ik ‘s “Dongju: The Portrait of a Poet,” focused on the life of the titular poet-activist (1917-1945), who, after modest success with his lyrical writing, found greater, lasting fame as the independence advocate imprisoned for his efforts who died a martyr for the cause. The background setting for the story provided a stark reminder of just how heavy-handed the imperialism was, with Koreans treated as strangers in their own land, forced to speak their invaders’ language and even take on Japanese names.

I doubt I will see a more important film than Cho Jung-rae’s “Spirits’ Homecoming,” which tackled the weighty and excruciatingly difficult subject of “comfort women” — the thousands of females from Japanese-occupied countries, including Korea, China, and the Philippines, forced into sexual slavery to service the Japanese army in the most dehumanizing of ways and at untold cost to their own psyches. After the war, those who managed to survive kept silent about this shameful experience, while paltry government attempts at restitution were made, until, late in the 20th century, a few brave, undaunted, and by that time aged souls stepped forward to expose the horrendous truth that had been omitted from Japanese history books as a matter of course.

I steeled myself for the film, wondering how Cho would handle his wrenching theme. I was relieved to find that while he did not soft-pedal the hideous violence of pubescent virgins being sacrificed to rapacious modern samurai, he did leaven the film with a modern-day story, interwoven throughout. In those sequences, to counterpoint the female victimization, he showed one survivor coming to terms with her past, somewhat, through the spiritual Korean tradition of shaman-ism, a practice traditionally dominated by the strongest and fiercest of women imaginable. I found particularly stirring a scene in which, hesitating about filing an official report about her past, she hears an indifferent clerk observing that only a crazy person would admit to such a past. “I AM that crazy person!” she declares with a fervor that made it one truly great movie moment.

Even while most filmmakers have avoided this delicate and painful history, it’s gratifying to know that the public, at least, is hungry for knowledge: The two low-budget films ranked among the top 10 in Korea for more than a month. “Spirits,” a $2 million film, crossed its breakeven point on its third day of release, to gross $23.9 million, while “Dongju,” which cost just $413,000 to make, took in $7.8 million.

Ellen Hollinger Martinez.| COURTESY: ELLEN HOLLINGER MARTINEZ

I was fortunate to grow up unning around an idyllic Waikiki of the 1960s, and a favorite playground was the International Market Place, a big exotic bazaar that was a masterpiece of tropical kitsch centered around a huge, beloved banyan tree. Don Ho performed there nightly, and we loved the free Sunday night hula show and reveled in the annual Easter egg hunt where, if you were lucky, you could find the coveted plastic orb containing free passes to the Kuhio Theater, where “The Sound of Music” ran for years.

All the marvelous kitsch has been gutted, painted coconut shells and rattan, and in its place now is a bling-y facsimile of Rodeo Drive, with a sparkling new Saks Fifth Avenue at its center. I was shocked to see beautiful clothes by Martin Margiela and Dries van Noten there, recalling a time when the only designer drag one could get there hid out in a special cabinet in the Liberty House Crest Room.

I’m happy to say, though, that the banyan is still there, more elegant than ever, turned into a lovely lounging area. And the hula show is, thankfully, less touristy, offering an honorable and splendidly entertaining survey of Hawaiian history conceived by local impresario Tihati.

I joined a small group of my Punahou classmates for an evening at the delightful Kanikapila Lounge in Waikiki, enjoying the music of talented Nathan Nahinu’s group Ka Hehena. One of our pack, Ellen Hollinger Martinez, surprised me by dancing the most beautiful hula to the classic song “Hi’ilawe.” It was not only her talent that wowed me, but also the pure joy and love that radiated from her as her graceful body and hands told the story of the titular waterfall that symbolizes personal strength and familial love. I’ve known many prominent hula dancers in my time, but somehow her name had never come up.

Beaming, Martinez afterward told me, “I’ve never had the drive to be front and center and the focus of attention. I am a very private person and very protective of my time and energy.”

She and her partner Keoki Aio present hula and music at two senior living centers, and twice a month join “the aunties who sew their beautiful computer lei” in “sit-down hula action with live nahenahe [soft, gentle] music.”

She also performs aboard a catamaran that carries out burial-at-sea ceremonies for Japanese guests.

“I sing ‘Aloha oe’ and ‘Amazing Grace.’ The captain blows a conch shell and sometimes I do a very simple chant,” she said. “My whole joy is to create a warm, loving, peaceful surrounding with honu [sea turtles], dolphins, and rainbows who make guest appearances.”

Martinez sometimes teaches a guest a few basic ukulele keys.

“This feeling of feeling loved and included stems back to days of music and dance with family gatherings with Aunty Irmgard Farden Aluli, the composer of many beloved Hawaiian song classics like ‘Puamana,’ ‘Emaliu mai,’ ‘Laupahoehoe,’ and so many others. Hula to me has always been about self-expression, storytelling. There is no right or wrong; the interpretation is from within. As a child, I was always surrounded by music. Aunty Irmgard used me as a soloist, which probably helped my confidence in sharing.”

Martinez’s late husband, accomplished local musician Paul Martinez, was also a huge influence.

“He taught me a lot about love and his journey, his talents were amazing,” she said. “His music arrangements were so beautiful and I loved to hula to them. He was a master ukulele artist and vocal arranger of close four- and five-part harmony. We were 25 years married.”