Just weeks after the Supreme Court ruled that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects LGBTQ people from employment discrimination, the court took away that protection from most LGBTQ people who are employed as teachers by religious schools.

In a July 8 ruling expanding a “ministerial exception” to anti-discrimination laws that it had recognized under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights eight years previously, the court held that employees of religious schools whose job entails teaching religion enjoy no protection against discrimination because of their race or color, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability. The court’s vote was 7-2.

The name of the case is Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru.

The prior decision, Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, involved a teacher at a Lutheran Church school, whom the court found to be, in effect, a “minister” of the Church, since she had been formally “called” to the ministry by the congregation after a period of extended theological study, and who had even claimed the tax benefits of being clergy. Although the teacher in question did not teach religion as her primary assignment, the court found it easy to conclude that it would violate Hosanna-Tabor’s right to free exercise of religion under the First Amendment for the government to intervene in any way in its decision not to continue this teacher’s employment, even if — as the teacher alleged — she was being discriminated against because of a disability in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

The July 8 decision involved two teachers at Catholic elementary schools in the Los Angeles Diocese. Neither of them was formally a “minister” and neither of them had extended religious education. As grade school teachers, they each taught the full range of subjects, including a weekly unit on Catholic doctrine at appropriate grade level for their students, but the overwhelming majority of their time was spent teaching arithmetic, science, history, reading, and so forth — the normal range of what a grade school teacher covers, but with an overlay of Catholicism. They also were supposed to pray with their students every day, and to attend Mass with them weekly.

One of the teachers claimed that she was dismissed because the school wanted to replace her with a younger person, leading to a lawsuit under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act. The other claimed she was forced out because of a disability in violation of the ADA. In both cases, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, reversing trial judges, found that these teachers could sue their schools for discrimination because they were not ministers.

The Ninth Circuit looked to the Hosanna-Tabor ruling and found that unlike the teacher in that case, these teachers did not have extensive religious education, were not “called” to ministry or titled as ministers by their schools, and were essentially lay teachers whose time teaching religion was a small part of their duties.

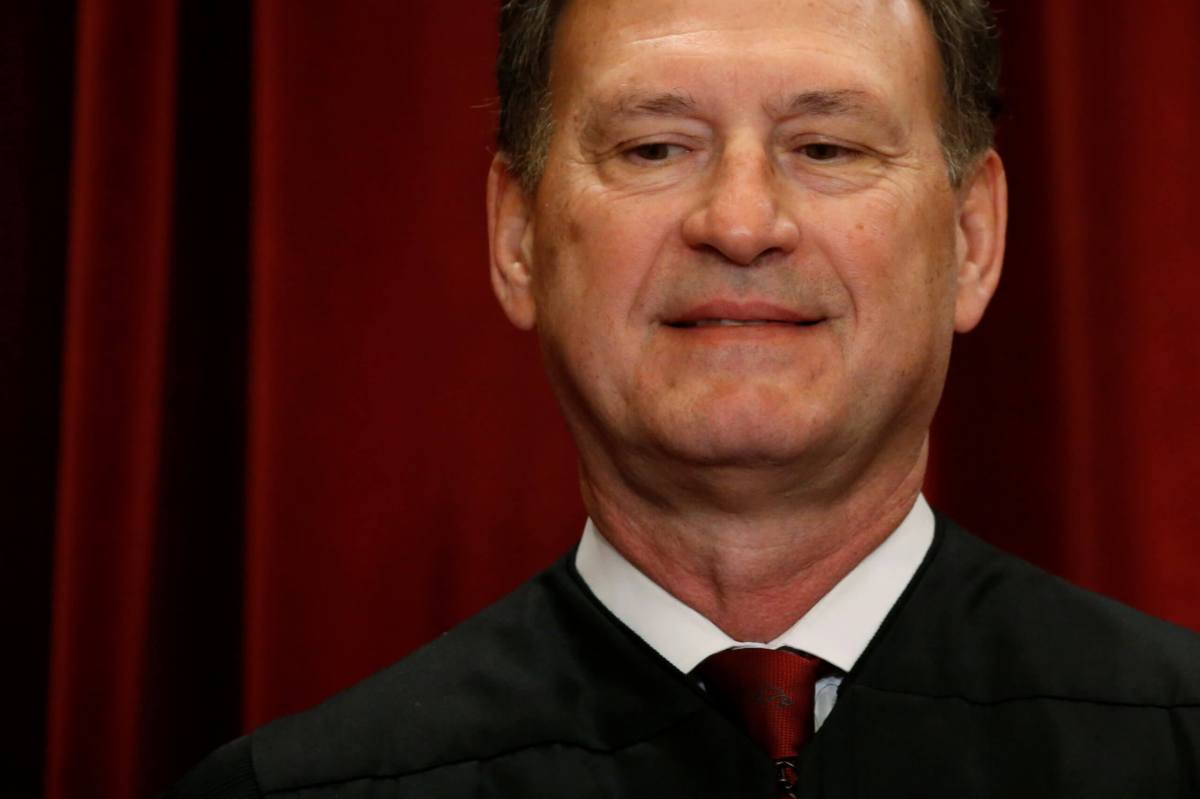

Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the Supreme Court, said that the 9th Circuit had misinterpreted the Hosanna-Tabor case. He rejected the idea that there was a checklist that could be mechanically applied to the question whether somebody is a “ministerial employee,” instead focusing on the religious mission of the Catholic School and the role the teacher plays in that mission.

“The religious education and formation of students is the very reason for the existence of most private religious schools,” Alito wrote. “And therefore the selection and supervision of the teachers upon whom the schools rely to do this work lie at the core of their mission. Judicial review of the way in which religious schools discharge those responsibilities would undermine the independence of religious institutions in a way that the First Amendment does not tolerate.”

In a concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas (joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch) argued that the court needn’t even probe into the details of the teachers’ employment, but instead should defer to a religious school’s determination whether their employees are excluded from coverage of anti-discrimination laws because of the ministerial exception. However, the court was not willing to go that far, and Justice Alito’s opinion made clear that how to classify an employee of a religious institution is a fact-specific determination that does require looking at the job duties of the employee.

In her dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, rejected Alito’s contention that the court’s ruling was a faithful application of the Hosanna-Tabor precedent. Although the court had not explicitly adopted Justice Thomas’s “deference” approach, she charged that it had actually adopted Thomas’s approach when it classified these teachers as covered by the ministerial exception. She wrote that “because the Court’s new standard prizes a functional importance that it appears to deem churches in the best position to explain, one cannot help but conclude that the Court has just traded legal analysis for a rubber stamp.”

To the dissenters, there was a world of difference between the teacher in Hosanna-Tabor and the teachers in this case, and they could see no good reason why church schools should be free to discriminate on the full list of grounds prohibited by anti-discrimination laws when the schools had no “theological” reason for discharging the teachers.

Federal anti-discrimination laws specifically allow religious schools to discriminate based on religion, but not based on such grounds as race or color, sex, national origin, age or disability, except for their “ministers,” as to whom traditionally churches would have total freedom to decide whom to employ. The Supreme Court long recognized churches’ freedom from government interference in employing “ministers.” Hosanna-Tabor extended the concept from clergy to some religious teachers, but Sotomayor argued that this new decision takes that concept too far away from traditional religious leadership roles, taking protection against discrimination away from thousands of teachers.

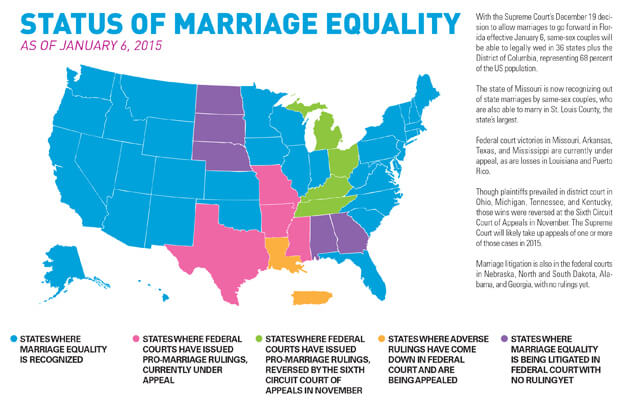

The court’s ruling may have an immediate adverse effect in lawsuits pending around the country by teachers who have been systematically fired by religious schools — almost entirely Catholic schools — after marrying their same-sex partners in the wake of the Obergefell decision five years ago. By rejecting Justice Thomas’s “deference” approach, the court leaves open the possibility that some of these discharged teachers might be able to prove that the “ministerial exception” does not apply to them, but, as Justice Sotomayor suggests, in most cases courts will have to dismiss their discrimination claims if their job had a religious component similar to the elementary school teachers, even if that was only a minor part of their role.