Eclectic series of performances suggest the riot that is the advancing spring

Female prototypes, era icons, and super heroines passed through sci-fi space in this complex meditation on better days and faded memories. Impressionistic video added texture and referents.

Guest Paige Martin entered intrusively, spilling real life into the performance, which had already begun. A former child beauty queen, contemplative in her tiara, turned her palm over and over again, as if expecting something to appear. A manic bride dashed from place to place, even up to the balcony, searching, scrambling. Was she jilted?

A freaky 70s mod freed herself by shedding her wig. And an ex-circus performer danced brashly to New Order; the 80s must have been good for her. Throughout, the set designer entered to adjust the scenery. It was all anchored by a binary duet that never interacted with these women. Twins in red dresses, they mirrored each other, but were unaffected by the collective past that haunted their midst.

Chauvinistic is a one-word description for this program, with every stage relationship firmly rooted in stereotypical gender roles and couplings. “27’ 52””is remarkable for its singular moment of male-male partnering (a lift) and an ambiguous glimpse of female nudity. Still, the dancing is venerable and “Last Touch” is a significant work.

More than just luxurious visuals––Victorian costumes and architecture with a touch of the surreal and white cloth spilled across the stage floor––the excruciatingly slow motion of six dancers in three scenarios and the anxiousness of the repetitive piano note got under your skin. At the climax, a screech rang out, lights flared, pages burned, and, in the blink of an eye, everything returned to where it began.

It was if we were watching ghosts of the past trapped in a recurring dream, inhabitants of purgatory, like Sisyphus, doomed forever to repeat their feeble actions.

This is what live performance is all about. The tension created between the audience and the performers in “Both Sitting Duet” is something special, unique, and essential. Without a score and without a conductor, two ordinary, middle-aged men seated side by side in plain wooden chairs exchange a symphony of repeating and varying gestures. Simple, yet so refined.

What made it profound was not the quiet, but the way they communicated––not with movement, not even with their eyes, but with something unseen and unspoken yet understood and felt by everyone present. Clearly not an improvisation, this piece nonetheless exuded some of that aura. It was dance in a much less presentational context, and not just theoretically for a change.

Stripped of most artifice and all media save the lights, it became ritualized through the audience’s collusion or collision with the silence.

Minimal music, soft lighting, and themes of alienation and fleeting acts of human interaction created a somnolent-on-the-edge-of-dreamy effect in Charles Linehan Company’s U.S debut.

Two half-hour works, the tense and hypnotic “Grand Junction” and the fine “New Quartet” provided ample evidence of the London-based Linehan’s success at home with the company’s clear and engaging movement vocabulary and strong technical and emotional performances.

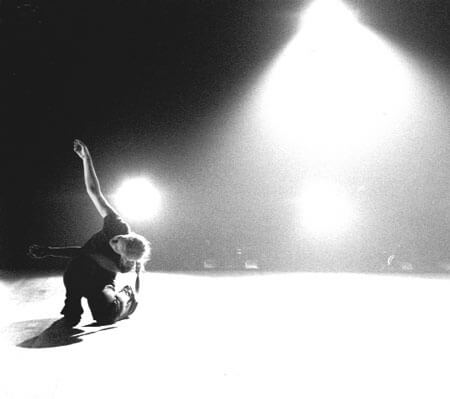

Reaching, darting, spinning, and melting out of the darkness, Andreja Rauch and Greig Cooke approached the audience and each other, only to retreat again in “Grand Junction.” They seemed more content in their own space, and even when they met, his focus was rarely, if ever, on her face. Rather, his eyes were often cast downward, more intent on the act of contact than what it communicated.

They danced a well-worn path between a comfortable reverberating distance and an almost unconscious desire for a union that they knew would never last.

Brian Brooks and his company of hoppy human movement machines – Jo-anne Lee, Weena Pauly, and Nicholas Duran––have both greenness and stamina going for them.

Brook’s newest work “Acre” is a random series of action exercises, hyper-repetitive rhythmic phrases that prompt the brain into beta. Backwards prancing in twos and threes, jump-push partnering, syncopated shoulder swinging, rolling and angular army formations in fours are the choreographer’s motifs.

Like his last work, “Dance-o-Matic,” dressed all in bubblegum pink, “Acre” is an array of bright greens––electric to lime to chartreuse––in lighting, video, costumes, and stage decor. When Kermit the Frog interrupts Tom Lopez’s score to sing “It’s not easy being green,” the dancers became heliotropic, reaching, waving their arms toward the sky like saplings in the sun. This wasn’t the end and might have been a better beginning, but the sections could have been performed in any order.