BY CHRISTOPHER BYRNE | Listening to the hideous things politicians are saying about one another these days, it’s amusing to think that one woman calling another a “dog show name” and then refusing to apologize could threaten to destabilize an entire social order. But that’s the story in “The New Morality,” Harold Chapin’s comedy now getting a sparkling production at the Mint under the direction of Jonathan Bank. The lightheartedness here can be deceptive; the piece is actually a quite serious metaphor for how relationships of all kinds can turn on a single comment or action.

Written during the early days of World War I and set in the summer of 1911 during a punishing heat wave, the play takes place on the river houseboat of Betty and Colonel Ivor Jones, where the couple have repaired to escape the heat of town. The boat is a fairly obvious symbol for the shifting foundation beneath the characters, as Ivor struggles to find a purpose now that he is out of the army and Betty tries to assert herself amidst the emerging women’s suffrage movement in England. Arguing with her neighbor Muriel over Ivor’s flirting and attentions, Betty uses the canine put-down and immediately takes to her bed, afraid she has mis-stepped and will become a social pariah.

Silly, yes, but the essential question — which should be familiar to any fan of “Downton Abbey” — is what accommodations must be made to changing times. Portraying this as a neighborhood kerfuffle, Chapin points out the banality of most of what passes for disagreements and offenses, real or imagined, many of which have significantly more dire consequences. In the third act, E. Wallace Wister, husband of the determinedly insulted Muriel, gives a long speech in which he takes a stand for progress and for the newly independent woman, what he calls “the new morality.” In the end, while there is no clear winner, Betty stoops — a bit — for the cause of peace. Progress may be plodding, but it can in no way be stopped.

Trials of the well-to-do in two plays — one delightful, one deadly

Bank has directed the piece with a clear eye and a sense of buoyancy that is first and foremost entertaining. There is a wonderful sense of life on the river, how close and insular it is, and the challenges that presents for the characters. The cast shines, particularly Brenda Meaney as Betty, who finds levels of depth and conflict beneath her frothy exterior. Michael Frederic is equally nuanced as Ivor, who struggles to balance his own concerns with a desire to keep the peace. Outstanding as Wister, Ned Noyes manages physical comedy and a quasi-Shavian monologue with precision and skill. The rest of the company — Clemmie Evans, Douglas Rees, and Kelly McReady — all do fine jobs in supporting roles. The marvelous sets are by Steven Kemp, and costumes by Carisa Kelly perfectly evoke the period.

It is always exciting to go to the Mint. The company’s commitment to find under-produced works is fascinating, largely because they always resonate with a contemporary audience.

It takes special talent to craft a one-act play that is as tedious and pointless as A.R. Gurney’s “Love and Money,” now flopping about over at the Signature. Gurney, who has tirelessly chronicled the button-down drama and Bombay Sapphire-soaked tribulations of the super-privileged, has often been entertaining. His latest piece, however, is a lazy bit of playwriting that is more of the same but less in almost every respect compared to the rest of his work.

Cornelia Cunningham, snug in her Upper East Side brownstone, suffers under the weight of having too much money and so, having had the pleasure of it for 70 years or so, is planning to give it away in atonement for past sins. A young man presents himself at the door pretending to be a long-lost, unknown grandson. Oh, and Walker Williams, the would-be heir, just happens to be black, the product of an affair Cornelia’s wayward daughter had. (Gurney tries valiantly not to seem too racist in the exposition of this point, but at best it rings as false as the rest of the play.)

If at this point, you’re thinking you’ve seen this play before, you have. John Guare’s “Six Degrees of Separation” had a great deal more to say. Cornelia, in fact, acknowledge the similarity of her situation to the Guare play, but that just makes this one seem twee and labored. The play lacks any real resolution other than Walker being exposed as a bad liar and Cornelia, as a result, making some crazy deal with him to pay for his acting school — rather than set him up in business. In other words, she’ll use her money to control people the way she’s always done.

The story also includes a high-strung attorney who wants to protect Cornelia’s money, a salt-of-the-earth, clear-eyed Irish maid, and a girl who comes to get a piano donated to the drama department at Juilliard.

Maureen Anderman is perfectly cast as a generic emaciated Upper East Side geriatric widow, though she is wasted in this role. (Does anyone else remember her in “The Lady from Dubuque,” “The Man Who Came to Dinner,” or opposite Philip Anglim in the Scottish play?) Joe Paulik is decent as the young lawyer whom “the firm” sends to deal with Cornelia. Kahyun Kim is charming in the completely pointless part of the girl in search of a free piano, and Pamela Dunlap tries to channel Thelma Ritter from “All About Eve” as the maid.

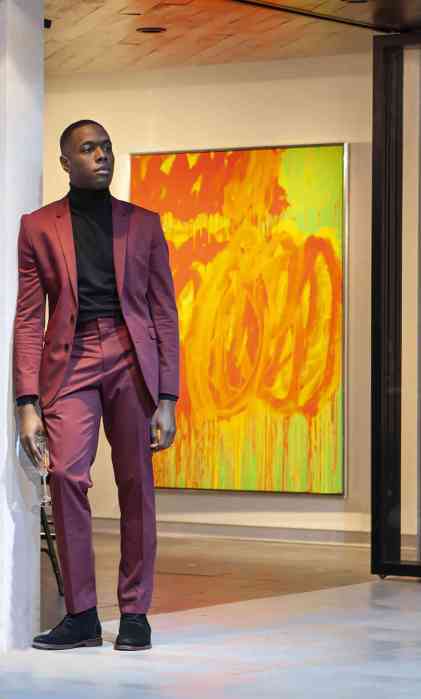

Unfortunately, Gabriel Brown as Walker is insufferable. Yes, we’re not supposed to believe him and he’s supposed to be annoying, but he’s also supposed to have some plausibility. Brown, who telegraphs every plot point, is a failure as a con man on all levels. He could use those acting lessons that are on offer.

Mark Lamos has directed with a leaden hand, and the whole mess lumbers along aimlessly. At one point or another, everyone sings Cole Porter, and then we get to go home.

THE NEW MORALITY | Mint Theater, 311 W. 43rd St. | Through Oct. 11: Tue.-Thu. at 7 p.m.; Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $27.50-$65 at minttheater.org or 866-811-4111 | Two hrs., with two intermissions

LOVE AND MONEY | Signature Theatre, 480 W. 42nd St. | Through Oct. 4: Tue.-Fri. at 7:30 p.m.; Fri. at 8 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $25 at signaturetheatre.org | 75 mins., no intermission