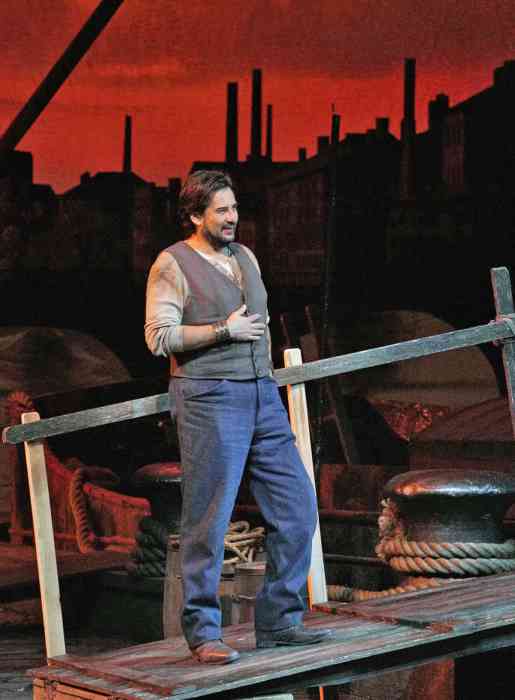

Baritone George Gagnidze as Alfio, with his break-dancing buddies. | CORY WEAVER/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

BY ELI JACOBSON | Though “Send in the Clowns” is Sondheim’s most popular song, very few people understand the significance of the title. It was generally thought to be a circus reference — whenever an accident or injury occurs in the ring, the ringmaster will send in the clowns to divert the audience’s attention. However, Sondheim in a 1990 interview said that the actress Desirée uses this theatrical catchphrase alluding to her own failed love life: “[I]t’s a theater reference meaning ‘if the show isn’t going well, let’s send in the clowns’; in other words, ‘let’s do the jokes.’”

David McVicar’s new Metropolitan Opera production of Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana” and Leoncavallo’s “I Pagliacci” flopped in Act One but turned into a hit after intermission with the addition of chicken puppets, dancing acrobats, and vaudeville routines (combined with searing melodrama and murder — “La commedia é finita”).

McVicar explained that the traditionally paired verismo one-acters are in his perception very dissimilar — “I Pagliacci” being the more musically and dramatically sophisticated of the two. The English director set both operas in the central piazza of the same Southern Italian town some 40 years apart — “Cavalleria” at the turn of the 20th century and “Pagliacci” just after World War II. In “Cavalleria,” the open curtain reveals towering stone walls in the background shrouded in stygian darkness with a brilliantly lit bare wood platform center stage (designed by Rae Smith). As Turiddu serenades Lola offstage, the chorus files in dressed in black and sit in wooden chairs surrounding the central platform. They silently stare down in judgment on the town pariah Santuzza, who stands alone center stage. The mood suggested not a sunny Easter morning in Sicily but something out of a Lorca tragedy like “Blood Wedding” or “The House of Bernarda Alba.” I began to buy into this concept — starkly minimalist, stripped down stylized tragedy — until the opening chorus, when the central platform began to rotate.

David McVicar gets halfway to truth with “Cavalleria Rusticana,” “I Pagliacci”

McVicar from then on went for directorial overkill, placing realistic props and fussy business on a stylized bare set with expressionistic lighting. A table sprung up from the wood floor while the chorus women demonstrated handicrafts in picturesque groups, suggesting costumed performers in a colonial village. The men started line-dancing in the streets like chorus boys in the musical “Zorba.” The nadir was Alfio’s aria “Il cavallo scalpita,” where the baritone jumped up on a table in Mamma Lucia’s wine shop while his trio of male back-up dancers (choreographed by Andrew George) did break-dance moves in front. All this “local color” looked arbitrary and foolish — typical of a director not trusting the material and reaching desperately for effects.

A few scenes with two characters alone onstage —– the jealousy duet between Santuzza and Turiddu for example — showed that less is more. Santuzza remained sitting downstage throughout the second half of the opera, eavesdropping on Turiddu in scenes where she has no part — pulling emotional focus from the other characters.

In “Pagliacci,” the stage was filled with brilliant color, the characters moved in bright daylight in recognizable spaces and acted believably in a logical, natural manner. The steamy atmosphere suggested Hollywood film noir (though in Technicolor, not black and white) mixed with Italian post-war neorealism in the Rossellini manner. The singers executed puppetry, clown acts, pratfalls, and dance routines like true circus professionals (coached by vaudeville consultant Emil Wolk). McVicar allowed no false moves and the action hurtled forward to a sizzling climax.

Tenor Marcelo Álvarez and baritone George Gagnidze performed double duty in both operas. Álvarez sang Turiddu with Latin fervor and sensuality, his Canio was less effective. McVicar conceives Canio as a broken down alcoholic wreck, and Álvarez's stooped, round-shouldered clown indulged in too much self-pity, exuding little physical menace in his jealous rages. On opening night, his soft-grained tenor didn’t open up on climaxes, further blunting Canio’s emotional force.

Gagnidze’s juicy, thrusting dramatic baritone was perfect for the bullish Alfio but his Tonio was bluntly sung and acted in a generalized style lacking vocal and verbal nuance.

Eva-Maria Westbroek’s Santuzza brought sympathy and warmth to the character, and for a non-Italian singer she handled the declamation well. Sadly her voice was not as focused as her acting. Though Santuzza’s music sits mostly in her warm middle octave, tonal pressure resulted in loosening vibrato and squally tops.

In “Pagliacci,” Patricia Racette dominated the stage, turning Nedda into the central character. Wilful, sensual, defiant — almost a Magnani-like figure — this Nedda was also an accomplished dancer, acrobat, and comedienne. Some hard-edged tone in her upper register suited both the verismo style and her mature, world weary characterization.

Lucas Meachem’s Silvio was hangdog in manner and phrased the arching lines of the love duet listlessly. Andrew Stenson’s brightly sung Beppe, Ginger Costa-Jackson’s insolent, overly brazen Lola, and Jane Bunnell’s stoic Mamma Lucia all provided quality vocalism.

Fabio Luisi conducted both operas with polished elegance and precise detail that did not preclude emotional intensity and dramatic force. Luisi’s “Cavalleria” had lyrical grandeur and “Pagliacci” a swirling, multifaceted orchestral brilliancy.

The term verismo refers to truth and reality in art — life lived onstage without artificial filters. McVicar’s very theatrical “Pagliacci” had this quality in spades but it was totally lacking in his “Cavalleria.”