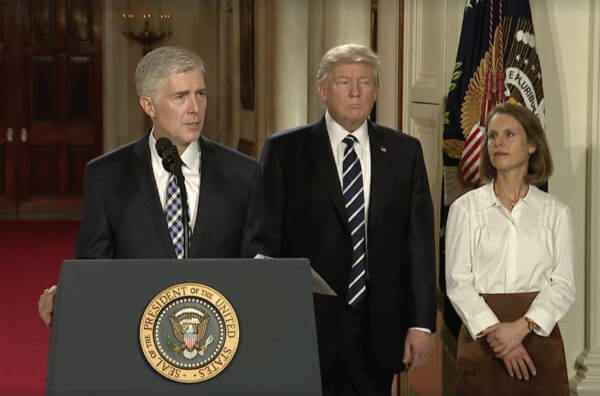

Lemon sports a pink pride button as he stands with Radmillo (l.) at the gay pride celebration in Srdja Dragojevic’s “Parade.” | DELIRIUM FILMS

The annual Human Rights Watch Film Festival consistently presents amazing films from around the world that demonstrate the struggle for human rights and equality in all its varied forms. The dramas and documentaries explore and expose the forces that threaten women, gays, opposition political parties, economic justice, freedom of the press… the list goes on and on.

Portrayals of courage in fight for LGBT, women’s rights distinguish Human Rights Watch Film Festival

This year, the festival has four films of interest to LGBT viewers, both domestically and internationally, with offerings from the US, Cameroon, and Serbia. These films provide a cinematic perspective on how far we have come — and how much further we must go.

A fifth film offers one measure of women’s advances in US society.

PARADE

Directed by Srdja Dragojevic

In Serbo-Croatian, with English subtitles

Jun. 17 at 9:15 p.m.

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at W. Third St.

Jun. 19 at 9:15 p.m.

Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center

144 W. 65th St.

Like many former Iron Curtain nations, the new countries that emerged from the breakup of Yugoslavia are virulently homophobic. The Serbian capital, Belgrade, is still a dangerous place to be yourself as a beating on the street is always possible. The 2010 gay pride parade there became an anti-gay riot that led to the injury of 78 police officers and 17 civilians and to the detention of 101 people for violent behavior. It took 5,600 policemen to guard just a few hundred gay and lesbian marchers.

Using these events as a backdrop, “Parade” is a fictional seriocomic look at an odd romance in which an engaged woman threatens to call off her wedding unless fiancé Lemon, a redneck Serbian brute, rounds up former compatriots from the Yugoslavian wars of the 1990s to guard gay activists at the 2009 parade. One of the galoots responds, “If we grant human rights to dykes and faggots, then even Gypsies and Albanians will want it.”

Lemon takes a road trip with Radmillo, a chubby gay veterinarian, in Radmillo’s tiny raspberry car, which is something of a graffiti magnet. It feels like “The Magnificent Seven” traveling through Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo to collect Lemon’s old war buddies. All this togetherness leads to changes of heart, as Lemon’s homophobic posse learn acceptance. “You guys, you’re really okay,” he says. “You’re normal.”

At the end of the movie, it’s just seven people on the LGBT side standing up to hundreds of attacking skinheads. The heartbreaking results lead the police to offer real protection the following year.

Using actual footage from the 2010 parade, the film was a blockbuster across the nations that formerly made up Yugoslavia.

BORN THIS WAY Directed by Shaun Kadlec and Deb Tullmann

In English and French with English subtitles

Jun. 21 at 9:15 p.m.

Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center

144 W. 65th St.

Uganda is Africa’s most notorious homophobic nation, but in Africa, the country that most aggressively jails people for being gay is Cameroon.

“Born This Way” follows four gay Cameroonians as well as Alice Nkom, the first woman admitted to the bar, who steadfastly defends imprisoned gays and lesbians. The penalty for being gay is three to five years in prison, and everyday LGBTs in Cameroon run the risk of bashings and death threats. Nkom brings two women from a remote southern town to Yaoundé, the capital city, after their public trial exposes them to potential violence.

We meet Cedric, who fears that coming out would mean losing his mother’s love. He is forced to move around surreptitiously after a street gang threatens him.

But there are also glimmers of hope. One woman journeys to her hometown and comes out to the Mother Superior who practically raised her and who now accepts her as she is. “She took the time to understand me,” the woman says. “That takes love.”

Nkom’s hope of taking the issue of homosexuality’s criminalization to Cameroon’s court is heartening, as well.

In one scene, we see a flabbergasting discussion between a lesbian and a man driving her, who asks a litany of personal sexual questions. It’s clear he has never met an out lesbian.

According to the film’s website, Cameroon’s president — Paul Biya, who has kept a tight grip on power since 1982 — has the power to drop the homophobic laws, has seen the film, and is considering a new, progressive direction for the nation.

DEEPSOUTH Directed by Lisa Biagiotti,

Cinematographer Duy Linh Tu,

Edited by Joe Lindquist

Jun. 15 at 7 p.m.

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at W. Third St.

Joshua Alexander explores an abandoned church in the Mississippi Delta in Lisa Biagiotti, Duy Linh Tu, and Joe Lindquist’s “deepsouth.” | ROYAL RED STUDIOS

America is about equality — and inequalities. When it comes to funding HIV/ AIDS prevention and care, the money dwindles each year. And so, in the documentary “deepsouth,” we follow Kathie Hiers, of AIDS Alabama, as she spends 120 days a year on the road lobbying for funding. Half of the AIDS deaths in America, we learn, are in the South.

“Funding tends to bounce from one hot group of demographics to another — with no balance,” Hiers explains. “The focus had been on gay men, then to black heterosexual women. HIV funding has not been distributed fairly.”

Elsewhere, Monica and Tammy prepare for a retreat for people living with HIV/ AIDS in rural Louisiana. They face challenges in figuring out how to feed 72 people for several days as well in getting those 72 to come to a safe space to share their experiences and fears in the first place.

We also meet Josh Alexander, a gay college student who gets most of his emotional needs met by his gay family-of-choice rather than from his relatives. A particularly poignant moment in “deepsouth” shows Josh walking among tombstones in the graveyard of a long-abandoned church. He stands at the forbidden pulpit — “the most sacred part of the church,” but also a place where a minister could be heard hectoring congregants about the sin of homosexuality and the punishment that results — AIDS.

“The only thing you get here in the Bible Belt is hypocrisy,” Josh concludes.

The film sheds light on an ignored part of the America, where people are striving to redefine traditional Southern values even as they struggle to forge solutions to ensure their survival. Many people living with HIV, we learn, are not eligible for any government programs until they receive an AIDS diagnosis, long after they should have entered care.

THE NEW BLACK Directed by Yoruba Richen

June 19 at 7 p.m.

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at W. Third St.

Jun. 20 at 6:30 p.m.

Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center

144 W. 65th St.

“I am a sistah in the movement. I am a S I S T A H. Let's be clear,” declares Sharon Lettman-Hicks of the National Black Justice Coalition. “This is the unfinished business of black people being free.” A documentary about African-American marriage equality activists taking on black ministers opposed to their goal, “The New Black” follows people on both sides of the issue in Maryland, where anti-gay groups forced a referendum last November on the same-sex marriage law enacted earlier in 2012.

The story’s roots, however, go back to the November 2008 election, which swept Barack Obama into office but also found California voters striking down marriage equality there. Until 2012, whenever same-sex marriage was on a ballot, opponents won — in 32 states. In Maryland, with a sizeable African-American population, the pulpits in some black churches became regular sources of homophobic rhetoric and hate-mongering. One African-American LGBT activist noted the challenge facing the pro-gay side — in the 1950s and 1960s, black churches were vital in providing “a community, a village, a sense of self-worth” at a critical time in history. Black gay leaders recognized that a public, grassroots response to bigotry where it was found was urgent.

The issue became divisive in the black community. Julian Bond, Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, and the president himself spoke out in favor of marriage equality, while many ministers persisted in making the typical “they want to redefine marriage” arguments. We see one bishop refer to Obama’s endorsement of gay marriage as “Judas’ kiss.” It’s astonishing to hear a black minister say that a radical “minority is attempting to impose itself on the majority.”

Black ministers were far from unanimous in their opposition to same-sex marriage. Pastor Delman Coates, a Baptist minister, unapologetically argues that “it's dangerous to legislate some parts of the Bible and not others.”

In the end, the gay activists’ efforts were rewarded — Maryland voters upheld the marriage equality law in the November election.

ANITA

Directed by Freida Lee Mock

Jun. 14 at 7 p.m.

Walter Reade Theatre

165 W. 65th St.

Anita Hill at the 1991 Senate Judiciary Committee hearings on Clarence Thomas’ nomination to the Supreme Court. | AMERICAN FILM FOUNDATION.”

The 1991 testimony of Anita Hill before the Senate Judiciary Committee during the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas often feels like an odd memory. An unknown woman publicly recalls instances of alleged sexual harassment in the workplace by someone nominated for the nation’s highest court. In moments better suited to “Saturday Night Live,” an all-male, all-white panel of senators makes this woman repeat comments like “Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?”

“Anita” offers a memorable look at what happened on October 11, 1991 — and since. The hearings put sexual harassment center stage. The first half of the film shows us the actual hearing, supplemented by commentary from today. Director Freida Lee Mock shows it all, and it’s hard to watch Hill’s discomfort as the senators humiliate her with their incredulous reactions to her embarrassing testimony. We see the anger and frustration of women spectators as Hill is treated almost like a hostile witness at a hearing chaired by Joe Biden, then the Senate Judiciary chair. For these men, from both parties and opposite sides of a highly polarized debate, winning seems far more important than finding the truth.

We also learn that, in the intervening 20 years, women have held annual “I Believe Anita Hill” conferences. Dignity and courage have proved stronger than the bullying on exhibit at the 1991 hearing. Since then, record numbers of women have reached state legislatures and Capitol Hill. Women are also coming forward in unprecedented numbers to lodge workplace sexual harassment complaints.

Anita Hill found her voice in 1991, and today she urges women everywhere to “raise your voice wherever you find it.” While Thomas remains on the Supreme Court, Hill has helped illuminate the complexities of female powerlessness, saying, “If I am not public, there would be a sense of victory they would have over me.”

Hill never again wore the blue dress from the 1991 hearing — it is still in its dry-cleaner plastic. Meanwhile, it has become a much-requested item by women in Ghana who saw it on TV.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH FILM FESTIVAL | Co-presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center | Jun. 13-23 | Various venues as noted above | Schedule, tickets at ff.hrw.org