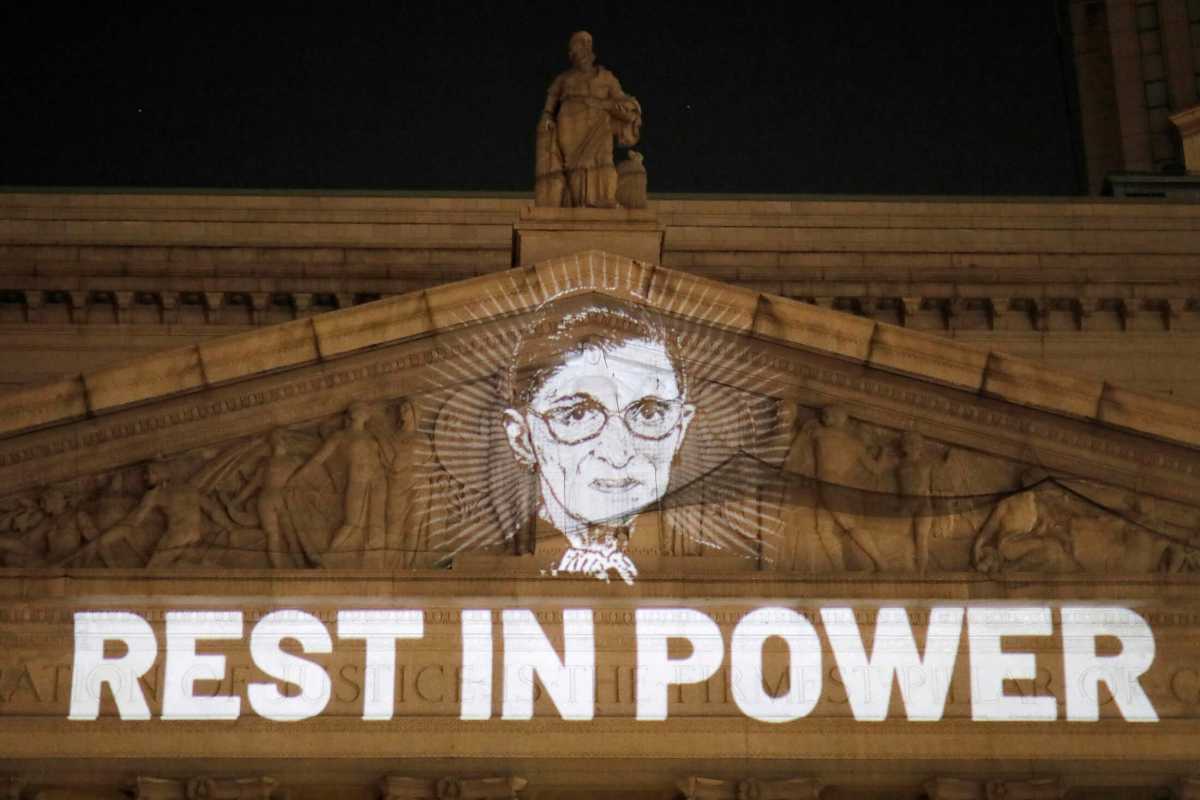

With Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s September 18 death at age 87, the Supreme Court lost a jurist who joined all of the pro-LGBTQ rights majorities and dissented from all adverse decisions except for the two in which the court was unanimous.

In 1993, she joined Justice David Souter’s majority opinion in Farmer v. Brennan, where the court ruled that a transgender inmate repeatedly subjected to sexual assault in prison could hold prison officials liable for damages under the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment by showing that they knew the inmate faced “a substantial risk of serious harm” and the officials “disregard[ed] that risk by failing to take reasonable measures to abate it.”

In 1996, Ginsburg joined the court’s opinion by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, Jr., in Romer v. Evans, holding that Colorado violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment by enacting a state constitutional amendment prohibiting the state or any of its subdivisions from protecting “homosexuals” from discrimination. Kennedy wrote that the state could not treat gay people as “strangers from the law” or categorically single gay people out for exclusion based on animus against homosexuality. The Court’s vote was 6-3, with Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Clarence Thomas joining Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissenting opinion.

Ginsburg joined Scalia’s opinion for the unanimous court in Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., a 1998 decision that embraced a textualist interpretation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, reversing a Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals decision that a man subjected to severe and pervasive sexual harassment by male co-workers in an all-male workplace — including being sodomized with a bar of soap and threatened with rape — could not bring a hostile work environment sex discrimination claim. To the contrary, the high court ruled, nothing in the language of Title VII suggested that same-sex harassment was not actionable, so long as the plaintiff showed he was harassed because of his sex.

Scalia memorably wrote that even though “male-on-male sexual harassment in the workplace was assuredly not the principal evil Congress was concerned with when it enacted Title VII… statutory prohibitions often go beyond the principal evil to cover reasonably comparable evils.” This approach provided a foundation for the court’s ruling this past June in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, finding that Title VII protected LGBTQ Americans from employment discrimination due to their sexual orientation or gender identity. It was the final LGBTQ rights victory in which Ginsburg participated.

In Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, the court in 2000 ruled 5-4 that the Boy Scouts of America enjoyed a First Amendment right of expressive association to exclude gay men from serving as adult troop leaders. Rehnquist wrote for the court, while Ginsburg joined two dissenting opinions, one by Justice John Paul Stevens and the other by Justice David Souter.

Ginsburg was part of the 6-3 majority in 2003 that found a Texas law penalizing “homosexual conduct” unconstitutional in situations involving private, consensual adult sexual activity. In Lawrence v. Texas, Ginsburg joined Kennedy’s majority opinion based on the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. Lawrence overruled the notorious 1986 ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick, which had rejected a due process challenge to Georgia’s sodomy law, asserting that “to claim that a right to engage in such conduct is ‘deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition’ or ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty’ is, at best, facetious.” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor concurred in the 2003 judgment but did not vote to overrule Bowers — a case in which she had joined the majority opinion — rather premising her vote on equal protection grounds. Scalia dissented, in an opinion joined by Rehnquist and Thomas.

Ginsburg wrote for the majority in 2010 in Christian Legal Society v. Martinez, rejecting a claim by students of that group’s chapter at Hastings Law School, a public institution in San Francisco, that the school’s refusal to give it official status because of its exclusionary membership policy violated the First Amendment. The court divided 5-4, with Kennedy and Stevens issuing concurring opinions, from which it was reasonable to infer that Ginsburg assembled her majority by seizing on the school’s policy requiring student organizations to allow all students to join and the fact that for the Christian group the policy’s ban on sexual orientation discrimination was a “sticking point.” Writing in dissent, Justice Samuel Alito angrily charged the court with enabling viewpoint discrimination by the public law school. Roberts, Scalia, and Thomas joined the dissent.

In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Ginsburg, in dissent, rejected the court’s 2014 holding that certain commercial businesses could assert First Amendment religious freedom claims to being exempt from contraceptive coverage requirements under the Affordable Care Act. In his opinion for the 5-4 majority, Alito noted — without any specific connection to the issue at hand — that an employer could not rely on religious freedom claims to defend against a race discrimination claim under Title VII. In her dissent, Ginsburg noted religious objections to homosexuality by some employers and questioned whether the court would find that employers have a right to discriminate on that basis. She specifically noted the case of Elane Photography v. Willock, in which the New Mexico Supreme Court rejected the defense mounted by a wedding photographer being sued under the state’s public accommodations law. In that case, the US Supreme Court had recently denied the photographer’s petition for review. Ginsburg also pointed to a state law case from Minnesota involving a health club owned by “born-again” Christians who denied membership to gay people in violation of a local anti-discrimination law.

Ginsburg, of course, joined Kennedy’s opinions for the court in United States v. Windsor in 2013 and Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015. In 5-4 rulings in each case, the court invoked concepts of due process and equal protection to, respectively, invalidate the federal Defense of Marriage Act and strike down state constitutional and statutory bans on same-sex marriage. Between the 2013 Windsor decision and the Obergefell ruling two years later, Ginsburg became the first sitting member of the high court to officiate at a same-sex wedding ceremony. Some critics, consequently, called on Ginsburg to recuse herself in the Obergefell case.

Also in 2013, in Hollingsworth v. Perry, Ginsburg joined the chief justice’s opinion holding that the proponents of California’s 2008 Proposition 8, which had amended the state’s constitution to define marriage solely as the union of a man and a woman, lacked standing to appeal a district court’s decision finding that measure unconstitutional. Since the state of California declined to appeal that ruling, the high court’s decision meant that Prop 8 was dead. Roberts’ opinion expressed no view as to its constitutionality, focusing entirely on the question of standing. That ruling broke up the customary alignment on LGBTQ rights cases, with Kennedy dissenting, in an opinion joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Thomas, and Alito.

In 2016, the court ruled that the courts of one state must accord full faith and credit to an adoption approved by the courts of another state in a case involving a second-parent adoption by the same-sex partner of the child’s birth mother in Georgia, where the family was temporarily residing. After the couple moved back to Alabama they split up, and the birth mother urged Alabama courts to refuse to recognize the adoption, arguing that had it been appealed, the appellate courts in Georgia would have found it invalid.

In 2017, in Pavan v. Smith, the court ruled that the state of Arkansas’ refusal to apply the legal presumption that the spouse of a birth mother is the parent of that mother’s child in a case where the wife of a woman who gave birth to a child sought to be named as a parent on the child’s birth certificate violated the 14th Amendment as construed in the Obergefell case. Ginsburg joined the majority, while in a dissent, Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Alito and Thomas, argued that Obergefell did not necessarily decide the case. Pavan reinforced the breadth of the 2015 marriage equality ruling regarding all the rights, benefits, and obligations of marriage.

In 2018’s Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, Ginsburg wrote a dissent, joined by Sotomayor, rejecting the court’s decision to reverse the Colorado Court of Appeals and the state’s Civil Rights Commission in their ruling that a baker violated the state’s civil rights law by refusing to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. Kennedy’s opinion for the court in the 7-2 ruling was premised on the majority’s conclusion that the baker, relying on First Amendment free exercise and free speech arguments, had been denied a “neutral forum” due to hostility to his religious views arguably expressed by two members of the Civil Rights Commission.

Ginsburg observed in dissent that there was no evidence of a lack of neutrality on the part of the Colorado Court of Appeals. She also agreed with that court’s conclusion that application of the public accommodations law to the bakery did not violate the First Amendment. In his majority opinion, Kennedy acknowledged Supreme Court precedent that private actors, such as businesses, generally do not have a First Amendment Free Exercise right to refuse to comply with state laws of general application not specifically targeting religious practices or beliefs. The majority, therefore, did not settle the underlying religious exemption assertion made by the Colorado baker in his lawsuit.

Finally, in this year’s Bostock case, Ginsburg joined Gorsuch’s majority opinion holding that discrimination in employment because of sexual orientation or transgender status is, at least in part, discrimination because of sex and so barred under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The vote was 6-3, with dissenting opinions by Alito, joined by Thomas, and by Justice Brett Kavanaugh. In his dissent, Alito asserted that the reasoning of the court’s opinion would affect the interpretation of more than 100 provisions of federal law, which he listed. The ruling extended protection against discrimination to LGBTQ employees in the majority of states where state laws do not provide such protection, although private sector protection under Title VII is limited to employers with at least 15 employees, which make up only a minority of all private sector employers.

As noted, Ginsburg’s two deviations from supporting claims of LGBTQ rights came in cases where the high court ruled unanimously. In 1995, she joined all the other justices in Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, Inc., holding that the Boston St. Patrick’s Day Parade was an expressive association whose organizers had a right to exclude a group whose message they did not want as part of their event. Even though the court held that Massachusetts could not enforce its public accommodations law banning sexual orientation discrimination against the parade organizers, in an opinion written by Souter, it affirmed that it was within the state’s constitutional authority to generally ban public accommodations from discrimination based on sexual orientation.

It is notable that five years later, Ginsburg was unwilling to assign the same expressive association free speech rights to the Boy Scouts.

In 2006, Ginsburg also joined a unanimous opinion by Roberts in Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights, Inc., rejecting a First Amendment claim by a group of law schools and faculty members that their institutions have a right to exclude military recruiters because of the Pentagon’s policy at the time excluding gay people from military service. Roberts premised the ruling on Congress’ power to “raise and support armies,” holding that it could constitutionally support this function by denying federal funds to educational institutions that denied military recruiters the same access they accorded to other recruiters.