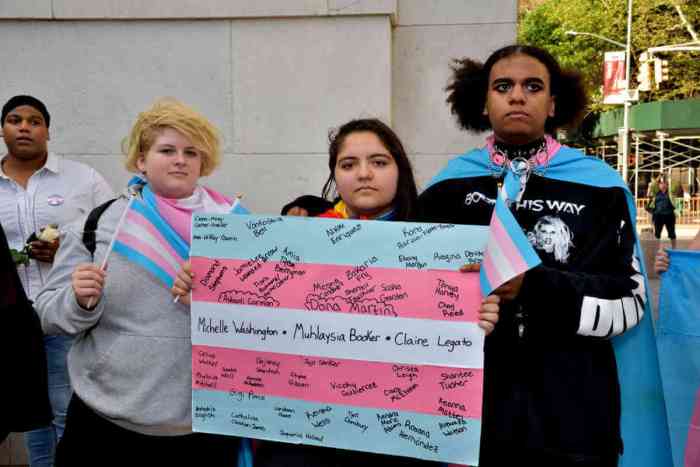

Upper West Side assemblymember sponsors bill for safe drug consumption spaces. MELISSA MOORE/ END OVERDOSE NY

Upper West Side State Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal is emerging as a principal player among legislators aiming to unravel New York’s decades-old, counterproductive War on Drugs. From her influential post as chair of the Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Committee, she is lead sponsor on a bill offering care for drug users while they are using. “They need help, not our punishment nor our judgment” is the principle behind her proposal to legalize safer consumption spaces, facilities staffed by overdose prevention workers able to administer naloxone should a person using drugs bought on the street experience an overdose.

“No one ever died in a safer injection site,” Rosenthal said at a January 29 Albany press event. “Let me repeat that again, no one ever died in a safer consumption site.”

Safer consumption spaces extend the logic of needle exchange programs, which provide injection drug users with clean syringes to prevent the transmission of HIV, hepatitis, and other blood-borne infections. Naloxone is a public health wonder. It restores normal breathing, and if you have guessed wrong and a person is drunk rather than high no harm is done. Users will overdose at safer consumption spaces, but they come out of the episode alive.

Upper West Side assemblymember sponsors bill for safe drug consumption spaces

Most importantly, naloxone is easy to use. It’s a nasal spray, so those aiding an overdose victim need merely stick the spray in that person’s nose and squirt. Only an hour of training is needed to administer it correctly.

The drug is, already, New York State’s response to the surge in opioid deaths. Emergency responders, homeless shelter staff and residents, and drug users and their friends and family can carry this kit to halt an overdose. That response, however, remains haphazard, depending on the lucky coincidence of a person carrying naloxone encountering the person overdosing. Cities all over the world have implemented a more organized response, allowing drug users to shoot up in clean, quiet surroundings using sterile equipment and having an overdose prevention worker steps away. These facilities conform to basic public health advice about heroin: “Don’t do it alone.”

US criminal law, however, largely makes it unthinkable that drug users could legally meet up to shoot up. Their conduct is illegal, and landlords hosting such space could lose their building and health care workers could go to jail. There is no freedom of assembly for drug users even in a health facility.

That is what Rosenthal’s bill, A.8534, would create by authorizing public spaces beyond the reach of the criminal law. It is macabre commentary on drug prohibition that proven public health policies are illegal without special legislation.

There is an urgent need: By every measure deaths are going up. “Nearly 65,000 Americans died” — more deaths in one year than the total for the entire Vietnam War — Rosenthal said of the nation’s record level of opioid deaths, before decrying the drastic escalation of deaths locally in recent years. “Here in New York State, the overdose death rate increased by 32 percent,” she said of the increase from 2015 to 2016. “In New York City, it increased by an astounding 46 percent.” The city health department’s final count for 2016 overdose deaths was 1,347 — the sixth consecutive year of rising deaths from unintentional “poisonings.”

“Safer consumption sites are neither controversial nor new,” Rosenthal noted, pointing out that the first one opened 32 years ago in Berne,Switzerland. “Since then they have opened in nearly 100 cities worldwide.”

Rosenthal originally introduced her measure in 2016, but this year it is part of a concerted push to move legislation in the Assembly that will help the state break free from the shackles of a prohibitionist policy, which has failed, while giving users a hassle-free space for consuming drugs safely.

Rosenthal was joined at the press conference by several Assembly colleagues, including fellow West Sider Richard Gottfried, who chairs the Health Committee, and Crystal Peoples-Stokes from Buffalo, the lead sponsor of A.3506, which permits adult-use of marijuana as is currently the law in a growing number of states.

A fourth member of the Assembly on hand created a stir when she told the audience, which included public healthcare workers, advocates, and families whose children had overdosed, that safe consumption spaces would offer comfort and support to people who today are shamed and isolated — and therefore at increased risk for fatal mistakes.

“It provides a positive touch point,” said Brooklyn Assemblymember Diana Richardson. “We are being progressive and providing a safe space for guess what? Something they will do anyway.” Noting she had visited such a space, Richardson said, “The individual came through the door and they were actually able to interact with someone. The person didn’t judge them, the person welcomed them.” Then, with a sly smile, she added dryly, “A person using many substances isn’t welcomed in many places.”

After the friendly greeting, Richardson explained, a user is “given clean materials… now we are talking about preventing hepatitis and a whole other host of diseases.” The concern such facilities show for the health of drug users is unique and increases the likelihood that healthcare workers will establish vital bonds of trust with those users.

This approach contrasts sharply with the tough love prohibitionist approach, which relies on the notion that substance abusers must hit bottom before remedial steps will be effective. Safe consumption spaces, based on the harm reduction philosophy behind needle exchange programs, instead aim to break the grip of hopelessness weighing on this stigmatized group, helping users identify personal competencies that could increase their sense of agency in taking charge of their lives.

Charles King, the CEO of the AIDS services group Housing Works, told the press conference that safe consumption spaces are “about saving lives, but just as important are about offering hope.”