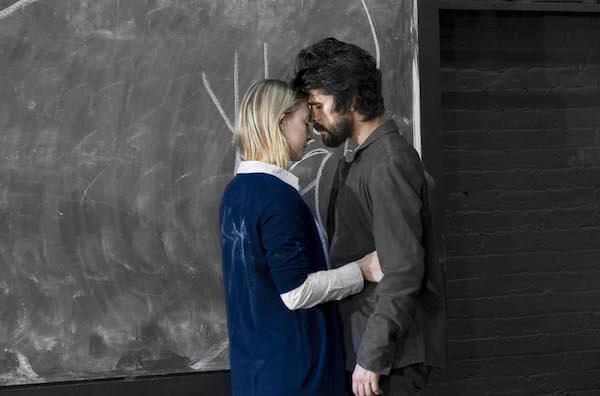

Flappers with guns from Matt Wolf’s documentary “Teenage.” | OSCILLOSCOPE LABORATORIES

Openly gay filmmaker Matt Wolf’s illuminating documentary “Teenage” is a fantastic mix of found footage, still photographs, and re-enactments of individual stories. The narration — representing the words of British and American boys and American and German girls — are supplied, respectively, by out gay actor Ben Whishaw, Jessie Usher, Jena Malone, and Julia Hummer.

Wolf, who wrote and directed the film, adapted gay author Jon Savage’s book “Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture” to show how teenage culture emerged during the first half of the 20th century. One common theme through those years for youth 16 to 24 was freedom. They found it in cars, clubs, clothes, music, and even work, which empowered them.

“Teenage” opens in 1904, when children as young as 12 years old would work in factory jobs up to 72 hours a week. Labor laws, the film explains, soon changed that, and adolescents were suddenly free to roam the streets. They formed gangs and created a problem for the authorities. Youth groups like the Boy Scouts were launched to control kids and in time ready them for war. When World War I came in 1914, it decimated the young adult population of Europe and was also felt in America.

Matt Wolf documentary examines defining styles of early 20th century teenage life

After the armistice, teens reinvented themselves as Bright Young People and attended Freak Parties, where males and females would dress androgynously. Later, they began using drugs and became politicized, working for social change. “Teenage” also chronicles the rise of Hitler Youth in Germany, as well as youth subcultures elsewhere, including the Swing Kids, Zoot Suiters, and In-Betweeners.

Gay City News spoke via phone with 31-year-old Wolf about “Teenage.”

GARY M. KRAMER: What were you like as a teenager?

MATT WOLF: Well, I was a very political teenager. I grew up in the Bay Area, and I got involved with other young people to protect gay and transgender teens in high schools. That was my whole world — the politics I was involved in.

GMK: Music is very important in “Teenage.” What did you listen to as a teen?

MW: A big part of my identity was music. I chose albums because of their artwork. I got into the Smiths and the Cure. I lightly identified with punk, even though I didn’t look punk on the outside.

GMK: What group of teenagers do you identify with or would you want to belong to if you had been a teen between 1904 and 1945?

MW: It depends on the decade. I think I would be a Jitterbug, because there was a political dimension to them — celebrating African-American culture and integrating social spaces. And they had incredible style and verve. In the 1930s, I’d be involved in politics and I’d be fighting for a different kind of future because that’s what I did as a teen in the 1990s.

GMK: Can you talk about the Bright Young People?

MW: I was searching for a gay youth movement. The gender play and queer material in the 1920s provides a striking resemblance to the Warhol Factory era. I felt queer teen experience was explored in this part of the film. It was hard to find gender outlaws in the early 20th century amongst youth. I wanted to highlight that.

GMK: How did you discover Jon Savage’s book?

MW: In college, I read “England’s Dreaming,” his definitive history of punk, which analyzed culture in a broader way. But it wasn’t academic — it depicted a time and a place. When I heard about “Teenage,” I was intrigued. I also love hidden histories and stories we think we know about but are told from a more obscure angle. We assume youth culture originated in the 1950s, with rockers and beatniks, and there was this whole pre-history.

GMK: What was your approach in adapting the book for the documentary

MW: At first, I thought it would be narrated by Jon as an essay-style film. But that didn’t work. Jon was older, British, and spoke with the authority of an expert. So I thought, how can we match the intensity and quality of the subject matter? I recorded some first-person voices from the material. And I told the story from the point of view of youth in the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany.

And the second part of the coin was that this would be a panorama, and I wanted to give emotional beats to the story to break up the march of time. Jon’s book is littered with obscure figures for a paragraph or pages. So I created portraits of teens that were balanced in race, class, gender, and personality — from larger than life Brenda Dean Paul and Tommie Scheel to rebels like the Hitler Youth and to the Boy Scouts.

GMK: What about choosing the voice-over talent? Did you have specific actors in mind?

MW: I wanted to work with really good actors. Jena Malone did a voice-over in “Into the Wild,” and there was a singerly performance quality to her. I had a mutual friend with Ben Whishaw and his voice was incredibly cool. He brought Keats poetry to life in “Bright Star.”

GMK: You mix still photographs with moving pictures and re-creation. What can you say about the power of the images?

MW: I worked with re-creations before with “Wild Combination” [his film about gay musician Arthur Russell]. I wanted to bring the characters to life, but they were obscure figures, with no footage or photos. So I used this device but in a more involved process, recreating newsreels and home movies.

Jon and I set out a rule that any story we told had to have a basis in archival footage. We were surprised that we found footage of so many of the youth cultures we depicted. I always privileged moving image material, but there are such remarkable photos from these decades that I had to honor the power of those images when I could find a purpose for them. An image of teenage flapper girls carrying guns is intoxicating. It had to find its way in to the film.

TEENAGE | Directed by Matt Wolf | Oscilloscope Laboratories | Opens Mar. 14 | Landmark Sunshine Cinema, 143 E. Houston St. btwn. First & Second Aves. | landmarktheatres.com