Well over a year ago, out of the blue, I was contacted by Rebecca Klassen, assistant curator of Material Culture at the New-York Historical Society (NYHS). She had been tasked with crafting an exhibition to mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, and heard through the queer grapevine about my collection of flyers and other ephemera from New York gay clubs from the 1990s. She wanted to take a look.

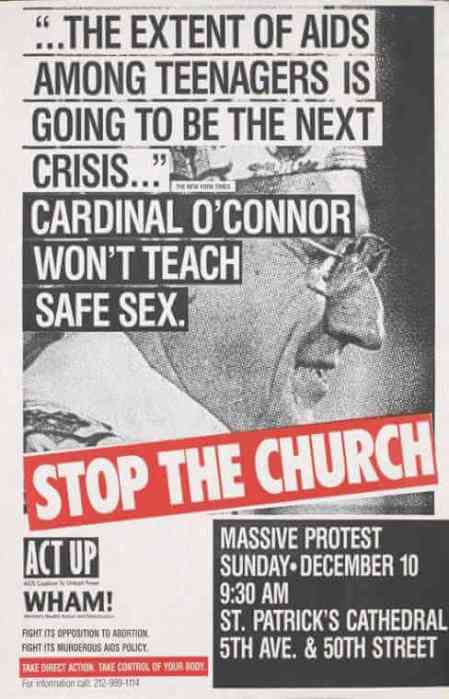

Klassen recognized that the 1990s were a heady and historic time for club-going in New York, when mammoth weekly gay parties at the Roxy, Limelight, Palladium, and Twilo, among others, reigned supreme. Not to forget scads of smaller venues like Sound Factory Bar, Crowbar, and Meat. These clubs were not only places to let loose, but a space to foster community and activism. They were safe havens for an LGBTQ community reeling from the AIDS crisis and often hosted benefits for Gay Men’s Health Crisis and ACT UP.

Upon exiting, promoters would hand out flyers advertising the next party, but most ended up in the trash. I was so taken by the images of half-naked hunks and drag queens I hung onto mine. I joined mailing lists and grabbed flyers from gay-friendly stores. I also collected posters, matchbooks, membership cards, and programs for special events like Wigstock.

After previewing a selection of the material, Klassen insisted on examining my entire collection — more than 1,000 pieces. Eventually, she chose a few items for the NYHS’ astonishing Stonewall 50 exhibition, now on display through September 22.

I was thrilled.

The exhibition is comprised of three distinct spaces. Klassen took the lead on the portion titled “Letting Loose and Fighting Back: LGBT Nightlife Before and After Stonewall.” It shines a light on the vital role nightlife played in shaping LGBTQ identity, developing political awareness, and building community. The exhibit chronicles the rise of gay bars from the 1950s and continues through the gay liberation movement.

You’ll find an astounding array of relics from the era, like a tattered copy of the 1969 Village Voice with a front-page story about the Stonewall riots, and a photo of the Sea Colony, a mafia-run lesbian hangout in the West Village in the 1950s and ‘60s (now the Art Bar). There’s also Club Kid Ernie Glam’s Sanrio cartoon lunchbox used in the 1990s, and a sign circa 1980 detailing the dress code for the Mineshaft, the notorious male fetish club in the Meatpacking District (“No Lacost [sic] Alligator Shirts”). My contributions can be found in this exhibit as well.

Another section, “By the Force of Our Presence: Highlights from the Lesbian Herstory Archives,” considers lesbian lives pre- and post-Stonewall. A special installation, “Say It Loud, Out and Proud: Fifty Years of Pride,” presents images from New York City Pride Marches and protests from the 1960s to today, as well as a timeline of LGBTQ milestones.

In conjunction with the exhibit, the NYHS held a Pride Day, which presented a storytelling show courtesy of The Generations Project, featuring stories from LGBTQ veterans and others. Visitors were encouraged to contribute photos, quotes, and other mementoes for the Stonewall 50 Time Capsule, a joint project between the NYHS and The Generations Project.

Instead of holding a traditional opening reception, the museum threw a huge, kick-ass dance party that joined uptown class with downtown sass.

I spoke with Klassen about the genesis of the Stonewall 50 exhibition, and why the endeavor is not only a commemoration, but also a celebration.

DAVID KENNERLEY: First off, let’s talk about the opening bash. What did you think of the turnout?

REBECCA KLASSEN: The opening was nothing short of a dream. The celebration took over two floors of the museum with multiple bars and a dance floor, and almost all of our exhibition galleries were open to explore. It showed how a party can be so much more than just a party. There were multiple generations of people from many walks of life, and they all genuinely had a lot of fun being together. Everyone from Randy Wicker, who began his out-front activism in the 1950s, to Club Kids from the Limelight era, to members of the house and ballroom community were sharing the same space. I knew the party was off the charts when a man with a walker started leading a conga line and people were hanging on with huge smiles.

KENNERLEY: Who else was there?

KLASSEN: Rollerena [legendary Studio 54 personality] gave remarks. BETTY performed a glorious a cappella version of their song “Rise.” Dan Daly from Marie’s Crisis played on Cole Porter’s piano while people sang along. JD Samson as DJ had people dancing right until the very end, which was 11 p.m. on a Thursday. Even the security and catering staff were dancing! We don’t have events on that scale very often, and our openings are usually very low key. But early on, I thought a dance party opening with a DJ of historical significance would be a critical component, because it would be an experiential facet of what the show is trying to convey. I’m grateful that the special events and development teams here believed in this idea and worked incredibly hard to make it happen.

KENNERLEY: I don’t normally associate the stately NYHS with edgy downtown artists, genderqueer folks, and drag queens. Can you elaborate on the significance of the diverse crowd this exhibit attracts?

KLASSEN: In the course of developing the Stonewall 50 exhibitions here, I came to realize that the New-York Historical Society has a more diverse array of visitors than people might suspect. Whenever we can make history relevant, accessible, and engaging to the broadest audiences, we’ve succeeded, and in recent years we’ve also been deepening our commitment to presenting stories of underrepresented communities. It’s important to people on a basic, existential level to see themselves reflected in museums and in history.

KENNERLEY: What sparked the idea to do a Stonewall 50 exhibition at the NYHS?

KLASSEN: In spring 2016 I received a LinkedIn request from someone at Heritage of Pride who was on their arts and culture committee. I don’t usually accept requests from people I don’t know, but saw that he was involved with Stonewall 50/ WorldPride planning. I pretty much ran to my boss to suggest that we commemorate the anniversary with an exhibition. Our museum explores the history of the nation through the lens of New York, so the decision to explore the broader meaning of a local event was a very easy one for us.

KENNERLEY: The field of LGBTQ history is so broad. How did you hone in on “Letting Loose and Fighting Back” for your portion of the exhibition?

KLASSEN: The decision was sparked by chats I had with Roy Eddey, a former administrator at New-York Historical who had been involved in gay publishing in the early 1970s, including the Gay Liberation Front’s Come Out! He described his vivid memories of dancing at the Saint and other nightlife experiences. The Pulse shooting happened shortly after those conversations, and many writers published reflections on the role LGBTQ nightlife played in their lives — discovering their people and growing into themselves. Even though the exhibit doesn’t extend chronologically to the Pulse shooting, it gave weight to the idea of exploring the history of nightlife, especially when considered alongside the Stonewall Uprising, which centered on a gay bar. Exploring LGBTQ bars and clubs as spaces of liberation, oppression, activism, and creative expression was in the project proposal, but we settled on the more evocative and accessible “letting loose” and “fighting back” when it came time to finally decide on a title.

KENNERLEY: Did you have any preconceptions about LGBTQ history that were altered by this experience?

KLASSEN: In order to convey a broad historical narrative, we tend to place people into groups and make generalizations. We also lump people into categories in the course of everyday life out of convenience or simple bias. But people are so much more complex than that, and move in multiple circles — places you wouldn’t expect. For instance, the first director of Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation was the artist George Dudley. He was very active in the leather scene, which is often associated with intense masculinism. The exhibition includes items connected to the Mineshaft that are part of his papers. However, he was also one of the driving forces behind the founding of the [drag-centric] Imperial Court of New York in 1985.

KENNERLEY: What else surprised you?

KLASSEN: The extent to which organized crime controlled LGBTQ bars and clubs — whether through ownership or coercion — through the 1970s. I had not given much thought to the mob in the history of New York City, since it tends to smack of sensationalism and dubious scholarship, but they really did have their hands in quite a bit.

KENNERLEY: It is an honor to contribute objects from my collection. The very first item you saw was an original program from Wigstock in 1991, and it made the cut. What was it about that program that spoke to you?

KLASSEN: I wanted to draw a through-line from the Pyramid Club in the early 1980s to Wigstock to “RuPaul’s Drag Race” We display the Wigstock 1991 program open to a spread drawn by Tabboo! [Stephen Tashjian] titled “The Official Drag Queen Starter Kit!” I thought it conveyed the playful DIY ethos, and I hoped visitors who perhaps weren’t even alive in the 1990s would find they could connect with it.

KENNERLEY: I was impressed that you came to my apartment and insisted on looking at every piece of my collection—over 1000 items. Did you pore over other collections with the same zeal in curating this exhibition?

KLASSEN: Yes. You never know what might lay hiding, and what information and connections it might yield. I also try to document as much as I can with snapshots in order to revisit the item later without having to arrange for another collection visit. It does take more time and a whole lot of data storage, but as you encounter more material, you discover new things in objects you looked at months ago.

KENNERLEY: You must have met some fascinating characters. Any notable people or stories you’d like to share?

KLASSEN: I feel truly privileged to have been able to speak to so many interesting and wonderful people, each in their own way, whether it’s because they threw a great party or organized a protest. Everyone is a fascinating character. Even you, David!

STONEWALL 50 AT NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY | 170 Central Park West at W. 77th St. | Through Sep. 22: Tue.-Thu., Sat., 10 a.m.-6 p.m.; Thu., 10 a.m.-8 p.m.; Sun., 11 a.m.-5 p.m. | $21; $16 for seniors; $13 for students; $6 for 5-13 years old | nyhistory.org