Veteran choreographer teases the odds to unite two better halves

By GUS SOLOMONS JR.

Full disclosure: I danced with Merce Cunningham’s company 30-odd years ago. Cunningham and John Cage’s aesthetic, along with Marshall (the-Medium-is-the-Massage) MacLuhan’s ideas shaped my own artistic values. So, I’m disposed to appreciate Cunningham, although I understand his non-objective abstraction is not everybody’s cup of tea––it “gets you” in the brain, rather than the heart.

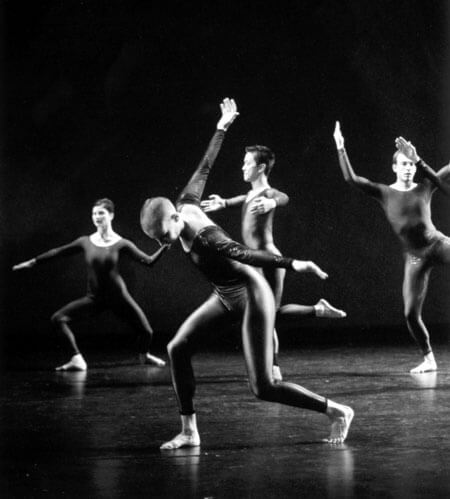

The continuum of unimaginably difficult computer-generated movement in his work—control, balance, and coordination—boggles the mind while ravishing the eye.

The computer allows Cunningham to combine movements in utterly counterintuitive combinations, wracking torsos in one direction while legs go in another, and arms yet another. Then, heroic dancers make it look fluid, organic, inevitable.

Cunningham has an unsurpassed skill at modulating textural densities and speeds onstage. But what drew many to BAM for a unique celebration of the golden anniversary of The Merce Cunningham Dance Company were the musical collaborators he’d chosen for this auspicious Next Wave Festival appearance: rock bands Radiohead from Britain and Sigur Rós from Iceland.

For the world premiere, “Split Sides,” tosses of dice determined the order of the two dance sections, lighting plots, music scores, and costumes. That’s not unusual for Cunningham, but the gimmick this time was that the die tossing was done onstage as part of the show.

After the opening night hoopla subsided, Friday’s performance reminded me how beautiful Cunningham’s dances can be.

Whether by conscious design or by “accident,” this world premiere was Cunningham at his most accessible. Two 20-minute sections—the décor, music, lighting, and costumes dictated by dice—seemed calculated to please. Cunningham’s series of stage pictures changed more radically and more quickly than usual—not necessarily a bad thing, since meditative contemplation is not the penchant of American audiences, addicted to speediness.

Each half of “Split Sides” accelerated with duration and, amid a matrix of wondrous dancing, each half had moments of breath-taking virtuosity, like a duet for the daredevils Holly Farmer and Daniel Squire who bite into the riskiest balances and leap with total confidence and physical commitment. A Jonah Bokaer solo of sharp dynamic changes and quick-as-a-flash articulations were astonishing.

The tosses were all even at this performance. Thus, first came a Heishman backdrop—crystalline, black-and-white patterns, an enlargement of one of his pinhole camera pictures. Then came Catherine Yass’ background, resembling tinted skyscrapers alighting on a lake of ice. The dancers first wore Hall’s black-and-white unitards, embossed with tangles of stripes and splotches, then jumpsuits, tinted in yellow, orange, red, and purple, under a grid of black diagonal lines. First, James F. Ingalls’s lighting plot 200, then 300.

The electronic hums, whistles, and beeps of Radiohead’s score, which preceded the celestial bells, squawks, and gurgles of Sigur Rós were not notably distinguishable from Cunningham’s usual accompaniments, except for an occasional persistent rock rhythm—hard for the dancers to ignore, which they must do to cleave to their own internal pulses that keep them in sync.

The New York premiere “Fluid Canvas,” which opened the evening, began leisurely, backed by motion-captured projections by Shelley Eshkar and Paul Kaiser, morphing into digital images by Marc Downie, accompanied by an electronic sound score by John King. Dancers, wearing James Hall’s shiny midnight blue or deep magenta unitards, gradually filled the stage, arching and curving their spines, as they walked forward high on their toes or backward in wide-legged deep pliés.

Dancers crowded the space, partnering up along circuitous pathways, then in various groupings: paired couples, trios, and solos. The pace gradually quickened until everyone was racing across the stage with lightning-fast, intricate foot patterns, torsos tilting, framed by rigidly angled arms. The visual-kinetic power accumulated to bursting concentration, suddenly laying bare the stage. The stillness registered for a brief satisfying moment before the lights went out.