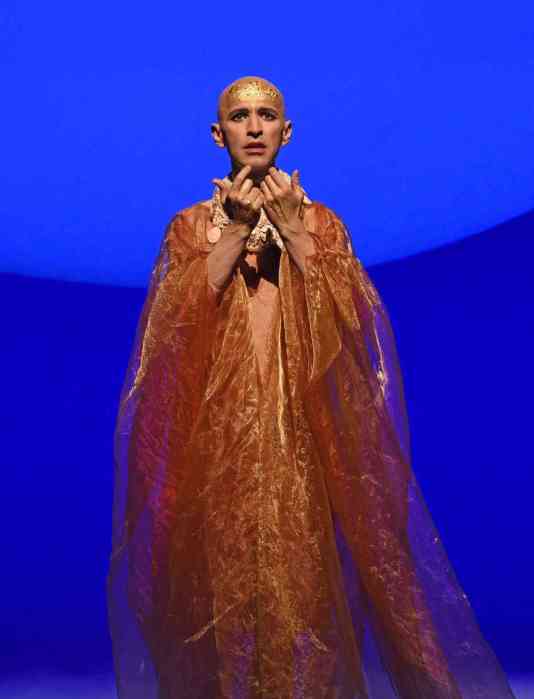

Spencer Hamlin as Rinuccio in Martina Arroyo’s “Prelude to Performance” production of Puccini’s “Gianni Schicchi.” | JEN JOYCE DAVIS/ JJ DAVIS STUDIO

Williamsburg’s National Sawdust has stolen the limelight from Le Poisson Rouge as the “go to” place for hip events in the classical industry. The space is interesting and presents all kinds of experimental work.

On July 20, it hosted the fourth and last performance of a production of Handel’s “Aci, Galatea e Polifemo,” an early Italian serenata by Handel. The gonzo staging by Christopher Alden — a sometimes brilliant director who in my experience has no ear whatsoever for the structure and atmosphere of this particular composer’s music — pretty much ruined the evening, but it was worth reviving the fine piece. Most audiences know only Handel’s magnificent later English-language version of the story, “Acis and Galatea,” but this serenata has lots of music gems that Handel reworked and recycled in later works.

The musical side yielded the finest results, thanks to conductor Clay Zeller-Townson and the fine ensemble Ruckus. Unfortunately, alone among the fine, alert players, the group’s baroque oboe — a bear of an instrument to play, I’m told — fell far short of the needed grace. Also — frankly — for all the theatrical intensity afforded by its intimacy, National Sawdust is a tricky, unresonant space for voices.

Tough “Aci, Galatea e Polifemo” slog at National Sawdust; promising Puccini evening at Hunter’s Kaye

Three impressive singers were on hand: Anthony Roth Costanzo as Galatea, Ambur Braid as Aci, and bass Davone Tines as Polifemo. That did not, though, guarantee much enjoyable singing. Costanzo’s mastery of meaningfully inflected recitative and softly projected legato lines showed Handelian stylistic attainment lacking in his colleagues. Braid sang flat continually and tossed in strident decorations; I’d like to hear her vibrant voice as Mozart’s Elettra or Anna in a larger space. Tines — with striking runway-ready looks and great dramatic presence — has understandably become something of a directorial totem. His voice has an impressive, distinct personal timbre. As Polifemo he growled at bottom and used a kind of Lieder-singer top, but a sense of line went lacking, with extra breaths and approximate coloratura in the (granted) daunting entrance aria. He distorted recits and their rhythms by bearing down on individual words with the kind of wannabe-Method Acting intensity Erwin Schrott dispenses in Mozart. Tines seems an artist of great potential, but maybe not an ace Handelian.

The Times preview writer who aptly welcomed the piece’s revival did not seem to understand that the story we saw of domestic workers oppressed and sexually harassed by an employer was Alden’s reworking of characters (nymph, shepherd, and mountainous cyclops) from Ovid. Having the countertenor and soprano play Galatea and Aci respectively, thus honoring the original voice casting, turned the harassment into a same-sex issue. Some steamy/ disturbing poses resulted, but to what end? Abuse of workers is a vital issue, but showing this well-heeled, well-connected, virtually all-white crowd (Tines, playing the oppressor here, was virtually the only African-American in the room) the worker couple toiling joylessly in scrubs seemed hypocritical; many in the crowd would scarcely acknowledge such people were they to encounter (or hire) them. The movement and direction (lots of posturing, Alden-playbook floor time, and carryings-on with straight razor) felt false from start to finish. Overactive sanguinary video imagery, (particularly horrible) pre-recorded tracks of floor scrubbing, and some of the music proved further distractions. The staging’s 90 minutes seemed endless. Any Handelian should welcome inventive stagings; alas, this one didn’t coalesce.

My first experience of Martina Arroyo’s “Prelude to Performance” series (Puccini’s “Suor Angelica” and “Gianni Schicchi” July 9 at Hunter’s Kaye Playhouse) was a far happier occasion — not because the stagings (by Ian Campbell) were fairly traditional but because they were internally consistent, detailed, and fully inhabited by the young performers. For some, these operas represented their first staged efforts; for others, like the young professional Michelle Johnson — who’s done leads in Philadelphia, Louisville, and Cooperstown — the event furnished a supportive environment for a first traversal of a difficult role.

The casts were well served by the vivifying hands of Maestro Willie Anthony Waters in the pit. Courtesy of Met veteran Loretta di Franco, good Italian diction was the rule. Johnson proved very impressive as Angelica, her warm spinto tone in good estate and the expression moving and unforced. With experience, she will inflect the text with even more depth, but as it was she evoked tears. Fine mezzo Leah Marie de Gruyl sang and played the Zia Principessa chillingly, but without caricature. Nicole Rowe piped delightfully in the key contrasting role of Genovieffa. The striking timbres of Melanie Ashkar (La Maestra delle Novizie) and Molly Burke (La Souora Zelatrice) stood out among a universally strong group of nuns.

For the climactic miracle, Campbell and set/ lighting designer Joshua Rose varied from the libretto’s early evening and gave us a starry firmament; it worked well enough. Like most “Schicchi” designers, Rose couldn’t resist placing Brunelleschi’s 1436 Dome into a work set in 1299. (In Eastern Europe, I once saw an “Andrea Chenier” with the Eiffel Tower visible in Act II’s 1794 Paris.)

Puccini’s lone comedy is that rarity, a genuinely funny score. Joshua DeVane had the vocal and comic chops to render a fine Schicchi, larger than life and not a wobbly buffo but a firm-voiced schemer. With a pingy tenor, Spencer Hamlin sang one of the best Rinuccios I’ve ever encountered. De Gruyl, Ashkar, and Rowe showed their versatility as Zita, Ciesca, and Nella; for once, their supplicating trio sounded seductive. Baritone Ben Reisinger (Spinelloccio/ Notario) also stood out; but again, the whole cast worked satisfactorily as a harmonious ensemble. Arroyo, in “Ernani,” was my very first Met diva; the admirable work she and her staff do in passing along the torch is a gift to America’s young singers and to New York’s summer audiences.

David Shengold (mailto:shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.