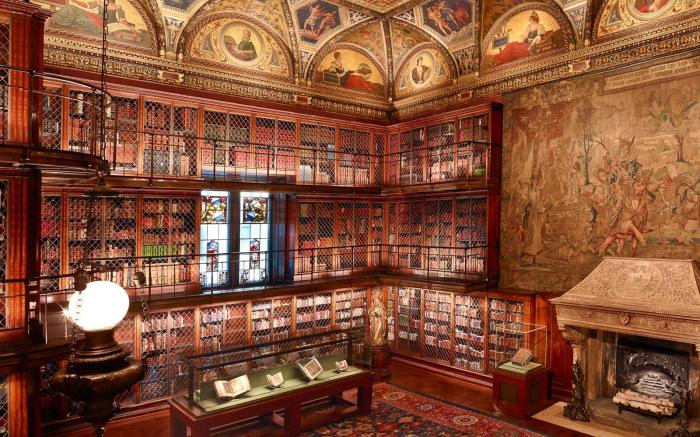

The 1970 film “Boys in the Band” is now available on Blu-ray. | KINO LORBER

You know what you are Michael? You’re a real person.”

“Thank you and fuck you.”

So Donald and Michael breezily banter early on in “The Boys in the Band,” Mart Crowley’s hilarious, tumultuous, and fascinatingly seminal play about a gaggle of gay men at a birthday party and the “Is he gay or isn’t he?” interloper who nearly upends it. A big hit and a point of considerable controversy for 47 years, “The Boys” is like an old boyfriend who despite a bad break-up is impossible to forget. That’s partially because it went on to influence such important works as Terrence McNally’s “Love! Valour! Compassion!,” and Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America.”

But it’s also a result of qualities that the piece embodies in and of itself. This Donald/ Michael exchange isn’t the work’s most memorable moment. The play is full of wittily bitchy verbal set-tos and slyly, potent one-liners (my favorite being Michael answering the phone with “Backstage, “New Moon!” ). Crowley maintains the speed and intensity from first to last, and in a vernacular that urban gay men who had “chosen families” like this one recognized at once back in 1968 but that the play’s straight admirers did not. With the 1970 film version being released this month on Blu-ray, a new look at “The Boys” is very much in order — for the work’s own sake and more importantly in relation to what we now call “the LGBT community.”

1970 film adaptation of Mart Crowley’s groundbreaking ’68 gay play hits Blu-ray vital as ever

There wasn’t a “community” back then. We were just “them” — outcasts, misfits, and, until 1973 when the American Psychiatric Association decided to “declassify” us, unfortunates suffering from a “mental disorder.” In 1968, we were “neurotics,” and our alleged “neurosis” demanded psychoanalytic treatment (Donald’s shrink, it will be remembered, cancelled a session with him just prior to the start of the action). This made “The Boys in the Band” something of a Mental Health Week freak show for straights, long curious as to “who these people are,” but chary of finding out at anything less than a safe distance. And thus we have the line-up of, in novelist (and Crowley compatriot) Gavin Lambert’s words, “Guilty Catholic, Angry Jew, Flaming Queen, All-American Mixed-Up Kid.” It was a set-up that Pauline Kael (who didn’t like the film, comparing it to 1940s war movies where bombers were invariably manned by a social cross-section of American heterosexuals) quipped “allowed the actors to behave on-stage as they did off.” Having had a daughter with bisexual — and later in life exclusively gay — filmmaker James Broughton, she knew something about it. But not everything. And most straight audiences knew nothing save for “gossip.” Of the “nudge-nudge, wink-wink” variety.

That Kenneth Nelson (Michael), Frederic Combs (Donald), Keith Prentice (Larry) Robert La Tourneaux (“Cowboy”), and Leonard Frey (Harold) were “that way” in “real life” was understood by those “in the know,” but of course never discussed in that long-ago era. Peter White (the mysterious party-crasher “Alan McCarthy”) was straight, as was Laurence Luckinbill (“Hank”) and, most memorably, Cliff Gorman (the ultra-swishy “Emory”). As for Rueben Greene (“Bernard”) he’s more mysterious in real life than Alan McCarthy — not only regarding his orientation, but in where he permanently disappeared to.

The person in all this whose sexual orientation counted the most, of course, was author Mart Crowley. His writing “The Boys in the Band” was partially inspired by a notorious New York Times piece “Homosexual Drama and Its Disguises,” written by the paper’s theater critic Stanley Kauffmann and published in the Sunday edition on January 23, 1966. Kauffmann set off a cultural firestorm by declaring that the three leading American playwrights were homosexuals and their works exhibited a “viciousness towards women” coupled with “lurid violence” and what he called “transvestite sexual exhibitionism.” Writing that he was “weary of disguised homosexual influence in the theater,” Kauffman charged their work offered “a badly distorted picture of American women, marriage, and society in general.”

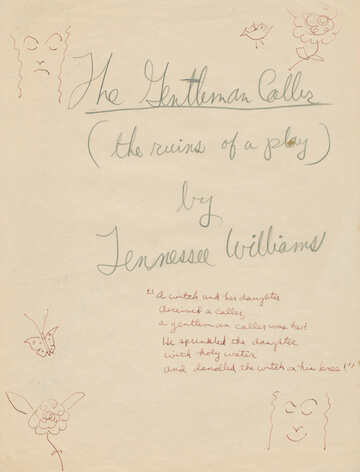

Kauffmann teasingly declined to name names, but it was clear that his targets were Edward Albee, Tennessee Williams, and William Inge. The raging antipathy of highly placed homophobes to this trio had long been understood, especially in the case of Albee. In a 1965 New York Review of Books piece smarmily entitled “The Play That Dares Not Speak Its Name,” Phillip Roth let loose on the Pulitzer Prize-winner. “In ‘Tiny Alice,’ the metaphysics, such as they are, appear to be Albee’s deepest concern — and no doubt about it, he wants his concerns to seem deep,” Roth wrote. “But this new play isn’t about the problems of faith-and-doubt or appearance-and-reality, any more than “Virginia Woolf” was about ‘the Decline of the West’; mostly, when the characters in ‘Tiny Alice’ suffer over epistemology, they are really suffering the consequences of human deceit, subterfuge, and hypocrisy. Albee sees in human nature very much what Maupassant did, only he wants to talk about it like Plato. In this way he not only distorts his observations, but subverts his own powers, for it is not the riddles of philosophy that bring his talent to life, but the ways of cruelty and humiliation. Like “Virginia Woolf,’ ‘Tiny Alice’ is about the triumph of a strong woman over a weak man.” Metaphysics were Albee’s deepest concern. But to a dim bulb like Roth all that must be brushed aside in favor of screaming “FAG!” as loudly as sotto voce allowed.

“The disaster of the play,” Roth declares, “its tediousness, its pretentiousness, its galling sophistication, its gratuitous and easy symbolizing, its ghastly pansy rhetoric and repartee — all of this can be traced to his own unwillingness or inability to put its real subject at the center of the action.”

“Tiny Alice” opens with two obviously gay prelates evidencing the “pansy rhetoric” Roth so haughtily turns his nose up at. They’re a mere “curtain-raiser,” but for Roth they must be front and center. He has no interest in dealing with the writer Albee actually is. “Tiny Alice” is not at all naturalistic and, therefore, in no way inclined to deal with “homosexuality” as a subject. In “The Zoo Story,” the brilliant one-act play that launched “Albee’s” career, Jerry is gay and his meeting in Central Park with the buttoned-down — and buttoned-up — Peter might be described as the World’s Worst Failed Pick-Up. But the play is in no way “about” sexual orientation. Its concern is with language, and its tradition dates back to the resolutely heterosexual August Strindberg, whose “Miss Julie” involves a comparable power play, though the couple is otherwise quite different.

The real target of Roth’s diatribe is Albee’s previous play, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,” which charts the long, dark, drink-laden night of the soul of two couples in Academia. George and Martha have Nick and Honey over for drinks following a faculty party and emesh them in a round of private games in which all the participants get to “read” one another with savage glee. Disclosing quite a bit about interpersonal relationships — particularly the thin line between love and hate — “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” both entertained and terrified, striking fear into the hearts of those heterosexuals who realized a gay man named Edward Albee had their number. For them this could not stand, and so the play was denounced as a “masquerade” in which two gay couples were disguised as straight ones. This was for a while taken as so much an article of faith that requests were made that the play be done with an all-male cast. Albee of course refused to allow this. And for anyone with an ounce of sense who has actually seen or read the play with any degree of attention, an all-male “Virginia Woolf” would make no sense at all.

As for Tennessee Williams, what his friend Gore Vidal called the “ritual attacks” on his sexuality — made for his daring to create authentic, complex, and deeply felt female characters — are well known. His efforts at dealing with gay sexuality most directly in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” and “Suddenly Last Summer” were either muffled by directorial interference (for all his theatrical savvy, Elia Kazan was clueless when it came to gay men) or charges of “sensationalism.” Less “sensational” Williams works like “Something Cloudy, Something Clear” never made it to Broadway.

Likewise with William Inge. whose “Picnic,” “Bus Stop,” and “Come Back Little Sheba” provided great roles for actresses but whose “gay plays — “Where’s Daddy?” and “The Last Pad” — were given short shrift or, in the case of the unproduced “The Boy in the Basement,” none at all.

Robert La Tourneaux and Cliff Gorman in “Boys in the Band.” | KINO LORBER

These were the odds Crowley faced — and prevailed against. The original production of “The Boys in the Band” ran for more than 1,000 performances Off-Broadway. And the film preserves its integrity, unprecedentedly keeping the original cast in the roles they created, even though none of them was a major star. The film’s release in 1970 came two years after the premiere of the play, but more importantly one year after the Stonewall riots changed everything.

Would any of the boys in “The Boys” have figured in Stonewall? One can easily see Emory fighting the cops. Stereotypically effeminate, he is also the most morally resolute of the bunch. He refuses to be anyone other than who he is, and he’s markedly compassionate toward Bernard, who collapses in sadness in the wake of the “Truth Game” that Michael forces everyone to play, having them make a phone call to the one person they love to tell them so. Hank and Larry call each other — a point Vito Russo emphasized in his writing about “The Boys” in “The Celluloid Closet.” Their honesty about their relationship — indeed the fact that they had a relationship, not just sex with each other — was quite important. Stonewall wasn’t their scene. In fact, in the film Hank and Larry are found at Julius’. That would have been Harold’s watering hole, too. Likewise “Donald.” But Cowboy would have been a familiar face at Stonewall (the bar not the riot ), as well as Bernard and even Alan, if he is indeed the closet queen he appears to be. But these characters, vivid as they are do not constitute “homosexuality.” Crowley presents a slice of gay life — not the whole cake. That’s also why “The Boys in the Band” is not “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” with an all-male cast. Albee is about the maintenance of illusion. Crowley is about overthrowing it.

But to find out what was really cooking in the New York Times’ kitchen — and in the the world the paper served — one must look back further than Kauffmann’s assault to December 17, 1963, when it ran a front page story titled “Growth of Overt Homosexuality in City Provokes Widespread Concern.” Written by one Robert Doty, it described gay life in New York in the wake of a series of raids on Third Avenue bars with gay clientele. Playing the all-too familiar Freudian saw, Doty wrote, “The old idea, assiduously propagated by homosexuals, that homosexuality is an inborn incurable disease, has been exploded by modern psychiatry in the opinion of many experts… [Psychiatrists] have what they consider to be overwhelming evidence that homosexuals are created — generally by ill-advised parents — and not born.” Doty went on to warn, “Some experts believe the number of homosexuals in the city is increasingly rapidly… and they have tended to become more overt, less concerned with concealing heir deviant conduct.”

Yikes! It’s a wonder that Albee, Inge, and Williams had enough cojones to go shopping at the local grocery store much less write any sort of play.

Mattachine Society member Randolph Wicker showed Doty around “the gay world” and gave him accurate information — all of which was resolutely ignored. But when Stonewall arrived, the truth Doty decried was impossible to ignore and “The Boys in the Band” in its own modest way shone a light on it. Crowley well knew what it was like to be born in what Michael refers to as “Hot Coffee Mississippi” and, on discovering oneself possessed of what used to be called “strange twilight urges,” to make plans to head for the Emerald City and create a new life for oneself with the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodsman, and the Cowardly Lion. Yes “The Boys in the Band” relates in many ways to the great gay ur-text “The Wizard of Oz,” though Dorothy often has more to fear from her friends than the Wicked Witch of the West.

Crowley put it best: “All the negative things in the play are represented by Michael, and because he’s the leading character, it was his message that a very square American pubic wanted to receive.” And that they did. But a very unsquare gay public saw something more. For all the backbiting, there’s also love. And that’s another reason why the play was a hit. Edward Albee knew it would be a hit. But he had no intention of following Crowley’s example, feeling obviously that “a gay play” would chew up the ground he’d so carefully worked to claim. And the truth of the matter is that while Crowley has written other plays of note, like the memory play about his parents, “A Breeze From the Gulf,” and his further set-to with Catholicism “For Reasons That Remain Unclear,” “The Boys in the Band” remains his signal achievement.

In 2002, Crowley wrote a sequel. Cleverly entitled “The Men From the Boys,” it centers on not a birthday party but a wake. Larry has died of AIDS. So by this time had Keith Prentice, who created him, Leonard Frey, the unforgettable Harold, Kenneth Nelson (Michael), and Robert La Tourneaux (“Cowboy”). The straight Cliff Gorman died of leukemia in 2002. He and his wife took care of La Tourneaux when HIV overtook him, and saw him through to his death.

“The Men From the Boys” ends with Harold disclosing that he too has seroconverted. But like the first play, its sequel’s last line is, “I’ll call you tomorrow.’ Someone ought to be called tomorrow to stage these works together in repertory. It’s the nicest way imaginable of saying to a very “real person” named Mart Crowley, “Thank you and fuck you.”