French director’s camera zeroes in on taboo love interests, human frailties

Although set during World War II, “Strayed” relegates the war’s specifics to the film’s opening and closing15 minutes. The heart of this movie lies in the lengthy central section, a four-character chamber drama. This portion could easily be reconceived as post-apocalyptic sci-fi or worked into any number of other rationales for isolating four people in a country house.

Téchiné uses war as a pretext to examine the breakdown of boundaries. When middle-class family life becomes impossible, possibilities open up. The borders between childhood and adulthood, maternal nurture and sexual attraction, and solitude and community become diffuse. The drama of “Strayed” rests in this zone.

Beginning in 1940, the film notes the beginning of Germany’s occupation of France. Odile (Emmanuelle Beart), a recently widowed teacher, flees Paris with her children, 13-year-old Philippe (Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet) and seven-year-old Cathy (Clémence Meyer). The family tries to escape to the south of France in her car. However, German Stukas bomb a group of refugees, killing several and destroying Odile’s car.

A tough teenager, Yvan (Gaspard Ulliel), takes the family under his wing. After spending a night outside, the group of survivors discovers an abandoned house. Yvan breaks in, and Odile and her children live there with him. The family grows dependent on Yvan’s hunting and fishing skills, but something seems a little off about him.

Téchiné is generally at his strongest when filming youth—as in “The Wild Reeds,” one of the best films ever made about a queer teenager, and “J’Embrasse Pas”—or middle-aged people—as in the Catherine Deneuve/ Daniel Auteuil films “Ma Saison Preferée” and “Les Voleurs.”

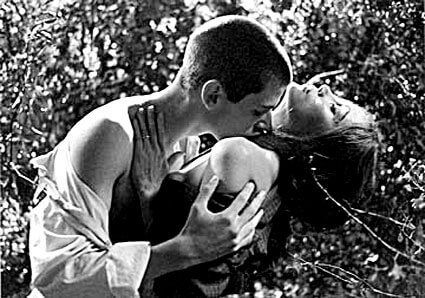

Odile is no longer an ingénue but not yet middle-aged. Yvan is a more typical Téchiné protagonist, a potential peer of the 1960s teens of “The Wild Reeds.” With his nearly shaven head, he looks like a refugee from the army, although he explains the extreme cropping as a response to a lice infestation. Unable to read a wine bottle’s label, he eventually reveals that he’s illiterate.

Yvan seems like the polar opposite of Odile, a proper bourgeois housewife. She’s embarrassed that she wet her pants after the raid. Beart’s performance is quite strong, embodying Odile’s ability to adapt quickly to her new surroundings. At first, she doesn’t realize that her world—especially her relationship with her children—has been upended. She’s wary of Yvan’s break-in, but no one else cares. Her children no longer obey her. Yvan, weapons collection and all, becomes the older brother Philippe never had.

In her one attempt to control Yvan, Odile buries his gun and hand grenade in the garden. Yet this isn’t really a malicious act, as she also decides to teach him how to read. Yvan fulfills several roles for the family, as both a potential lover and a surrogate son.

The pastoral setting of “Strayed” is extremely vivid. It lends a touch of unreality to the film, keeping the war’s violence and despair at a safe distance. The woods are benevolent, full of rabbits for Yvan to trap and frogs for Cathy to tame. Subtly, the film takes on the air of a fairy tale, a common technique for recent French films. Since a radio is hidden and clocks don’t tell accurate time, the story seems to take place out of time.

Téchiné doesn’t deliver on the promise of this portion of the film. Perhaps it’s inevitable that the narrative must bring the characters back to the real world of 1940. In any case, Odile and Yvan play out all the possible permutations of their relationship before leaving the house. Two middle-aged soldiers come by, bringing back the stench of war. The boundaries of “normal” life reassert themselves, ending a lovely, if unsettling, reverie.

However prosaic the conclusion seems, the film’s vision of wide-open space—both physical and mental—cannot be extinguished.