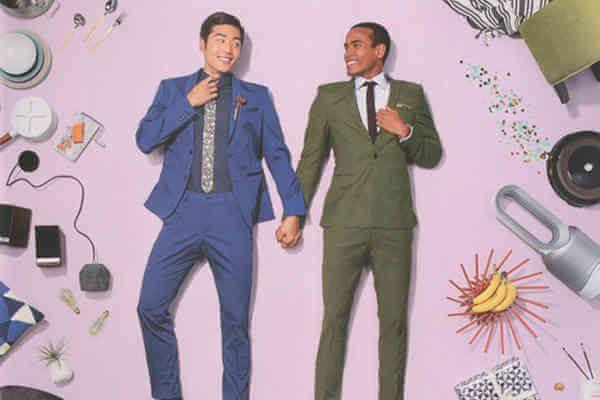

Curtis Lipscomb, executive director of LGBT Detroit, police LGBTQ liaison Officer Dani Woods, and Michigan State University professor Tim Retzloff discuss LGBTQ life in the city during the time of the 1967 Rebellion portrayed in Kathryn Bigelow’s film. | MICHAEL LUONGO

Tim Retzloff teaches history and LGBTQ studies at Michigan State University in East Lansing. He earned his Ph.D. in history in 2014 from Yale, where he studied under George Chauncey, best known outside academic circles for his landmark 1994 book “Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940.” Retzloff, in the tradition of his Yale advisor, is currently at work on his first book, “Metro Gay,” about gay and lesbian life and politics in the Detroit area from the end of World War II through 1985.

His writings on Michigan’s queer past have appeared in the anthology “Creating a Place for Ourselves,” the journal GLQ, the collection “Making Suburbia,” and Between The Lines, Michigan’s LGBTQ newspaper, where he had been editor. He also curates the website Michigan LGBTQ Remember, an online gallery of queer Michiganders from the past (michiganlgbtqremember.com/), and writes a companion blog on Queer Remembering (queer-remembering.blog/).

How queer politics, demographics tracked a big city’s yawning racial divide

Retzloff grew up in Flint, about 50 miles northeast of the university, and now lives in Lansing, the state capital, with his husband Rick. When Kathryn Bigelow’s “Detroit” — which looks at a 1967 police raid on the Blind Pig, a black social club, that led to widespread disturbances, known locally as the Rebellion — was released this past summer, Retzloff participated in a forum organized by LGBT Detroit (lgbtdetroit.org) along with the group’s executive director, Curtis Lipscomb, and Detroit’s LGBT police liaison, Officer Dani Woods, to discuss the queer community’s reactions to the movie. Later, he spoke with Gay City News about Detroit’s LGBTQ community during this pivotal time in the city’s history.

MICHAEL LUONGO: What was gay life like in Detroit in the late 1960s?

TIM RETZLOFF: Much of Detroit’s gay life in the late 1960s revolved around an expanding nightlife. With a couple exceptions, Detroit’s 20 or so gay bars served a white gay clientele. Queer people of color had only one or two bars to call their own. They created other means of socializing, such as roving and fixed drag venues and now-famous house parties hosted by local lesbian matriarch Ruth Ellis.

Some gay Detroiters did bridge the racial divide both socially and sexually, meeting in downtown movie houses, public restrooms, city parks, and private homes. In terms of organizing, Detroit’s gay activism paled in comparison to the increasingly assertive homophile movements in New York, San Francisco, and Washington, DC, during the same era. In 1967, the area had only one formal group, called ONE in Detroit, which was predominantly male, professional, and closeted.

ML: You also mentioned a gay connection to the Berry Gordy of Motown mansion.

TR: In the mid-1960s, a librarian at a suburban high school and his male partner bought a lavish 10-bedroom mansion in Detroit’s Boston-Edison neighborhood for a steal. As gay men were wont to do, they refurbished the home and hosted parties there, some gay, some not. At a February 1967 party for the librarian’s high school faculty, guests were treated to a surprise visit by Berry Gordy and the Supremes. Soon thereafter, the couple sold the home to Gordy.

ML: Tell me about the vice squad policeman who initiated the raid that set off the Detroit riots, and what he used to do to the LGBTQ population of the time. And it was a queer who finally did something drastic to him?

TR: John Hersey’s [book] “The Algiers Motel Incident” [on which Bigelow’s movie is partly based], includes an account of David Senack, one of the three real life Detroit police officers given fictional names for the film “Detroit.” Senack told Hersey about a vice squad sergeant named Victor De Lavalla, who was front and center in the Blind Pig raid that sparked the Detroit Rebellion of ’67. My own research into local prosecutions for gross indecency and homosexual accosting found De Lavalla listed as arresting officer in more homosexual cases than anyone else on the vice squad. According to Senack, De Lavalla “got his stomach slashed from end to end by a queer” early in his career.

ML: Talk also about the connections among policing of black bodies, queer bodies, and queer black bodies versus white queer bodies.

TR: Court cases from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s reveal that white people arrested while patronizing Detroit gay bars were more likely to be incarcerated than were white men arrested in parks, who could claim a temporary lapse from heterosexuality. Of the total who received jail time or prison sentences for homosexual offenses, roughly one-third were white and two-thirds were African-American. In Detroit, as in other localities, black bodies and queer bodies were policed by the local vice squad. Detroiters with black queer bodies were perhaps most vulnerable.

ML: You had mentioned the Virginia Park neighborhood that surrounded the Algiers Motel, the incident portrayed in Bigelow’s movie Detroit, was to a degree a gay neighborhood.

TR: The neighborhood had a strong gay presence in the 1960s. Two blocks to the south, gay people populated a number of small apartment buildings along Seward Avenue. The Diplomat Lounge, Detroit’s foremost drag showcase of the 1960s, was several blocks away on Second Boulevard. The Park Lane building, across the street from the Diplomat, was so gay that residents performed a same-sex wedding in the lobby in the mid-1960s. And, in 1972, Detroit’s first gay community center, the Green Carnation, opened just a block and a half from the Algiers Motel.

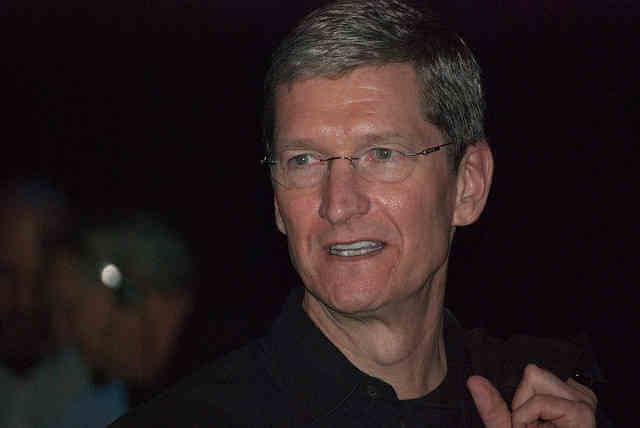

The Right Reverend Dr. James F. Jones, more widely known as Prophet Jones, was arrested in 1956 for making an “indecent proposal” to an undercover Detroit vice officer | JERRY COOKE/ LIFE MAGAZINE/ PUBLIC DOMAIN

ML: Long before the Rebellion, what were some of the main gay spaces/ neighborhoods in Detroit, and what made aspects of some of them, such as Paradise Valley, like Harlem in the ‘20s and ‘30s?

TR: White, working-class gay bars clustered around Farmer and Bates Streets downtown by the 1940s. In the 1950s, gay bars began to migrate farther out into the city, first to an area now touted as Midtown [near the Museum District], and by the early 1970s to Woodward and Six Mile Road. Meanwhile, from the 1920s through the 1950s, a queer presence was integral to the African-American enclave of Paradise Valley. Boxed in by redlining, deed restrictions, and white resistance to integration, Paradise Valley nonetheless became a vibrant nexus for black Detroiters where sissy bars shared space with jazz clubs and the Detroit Urban League. The area was bulldozed in the early 1960s for a freeway.

ML: Following the Rebellion, there were major splits among black and white gays — or had it always been that way? How did two spheres of gay life develop in the Detroit region in the decades following, making the city very different from other American cities and how did this impact bars, parades, and LGBTQ rights groups?

TR: Detroit’s LGBTQ landscape does, indeed, look different from other US cities. It’s a complicated map whose nuances tell us important things about cross currents of oppression and resistance, the spatial roots of differing strands of gay politics, and how race and racism have shaped LGBTQ life.

The urban violence of 1967 accelerated a pattern of white flight and economic disinvestment in the city that had already been underway since the end of World War II. Many white lesbian and gay people joined the white exodus.

A racial chasm helped precipitate the demise of the Detroit Gay Liberation Front in 1971, when participants divided over whether to include police oppression of blacks as part of a protest against the vice squad. In some ways, the rift continued on.

The focal point of white LGBTQ life in Metro Detroit today is suburban Ferndale, home to a gay mayor, Affirmations Community Center, and one of the few Detroit-area gay bars operating outside the Detroit city limits.

Within Detroit proper, LGBTQ people of color have created their own distinctive institutions, including the Ruth Ellis Center for homeless youth, Full Truth Unity Fellowship Church, and LGBT Detroit.

The Association of Suburban People was founded in 1975 in response to a sheriff’s crackdown on gay men gathering in a county park. ASP reflected a new desire for gay organizing beyond Detroit in suburbs that were almost exclusively white. The group reflected a politics of closeted discretion.

ML: Tell me more about the Palmer Park area developing as a gay white space, then a gay black space. And this is also near where Mitt Romney grew up, and where LGBT Detroit’s Pride Festival Hotter Than July takes place.

TR: Palmer Park is probably the nearest Detroit has come to having a gay neighborhood akin to Chelsea or the Castro or Chicago’s Boystown. Situated around Woodward and Six Mile, just to the south of an expansive namesake park where plenty of cruising went on, the area emerged as a gay neighborhood by the early 1970s. It included bars, bathhouses, a gay bookstore, and substantial gay occupancy in the Palmer Park apartment district.

The white gay population began to leave in the mid-1980s and numerous former residents lament the loss of the glory days when Palmer Park was gay, oblivious to or outright ignoring the fact that the area retains an LGBTQ presence in 2017, one comprising primarily people of color. Detroit’s premier black LGBTQ pride event, the annual Hotter Than July celebration, culminates with a picnic in Palmer Park, as it has each year since 1996.

The Romneys lived in Palmer Woods, a neighborhood of stately homes located north of Palmer Park.

ML: Who was Prophet Jones?

TR: Prophet Jones was a popular, fabulously flamboyant African-American religious leader who rose to prominence in Detroit in the 1940s and 1950s and was featured in such national magazines as Life, Newsweek, and the Saturday Evening Post. The Detroit police arrested him on a morals charge in 1956 for making an “indecent proposal” to an undercover vice officer.