The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center and other defendants have moved to dismiss a lawsuit filed against them that charged they discriminated against the conservative founder of the #WalkAway movement and two of his colleagues when The Center first agreed to rent a room to the group for the meeting and then withdrew that agreement after a community outcry.

“The facts as alleged in plaintiffs’ complaint fail to establish an intent to discriminate on the basis of plaintiffs’ sexual orientation and/or gender identity,” Kevin Loftus, a partner at O’Connor, McGuinness, Conte, Doyle, Oleson, Watson & Loftus, wrote in an August 20 filing in Manhattan Supreme Court. “Plaintiffs simply make conclusory allegations and over-exaggerated claims regarding a simple contract dispute. Absent evidence suggesting that defendants engaged in discriminatory practices because of plaintiffs’ membership in a protected class, the complaint must be dismissed.”

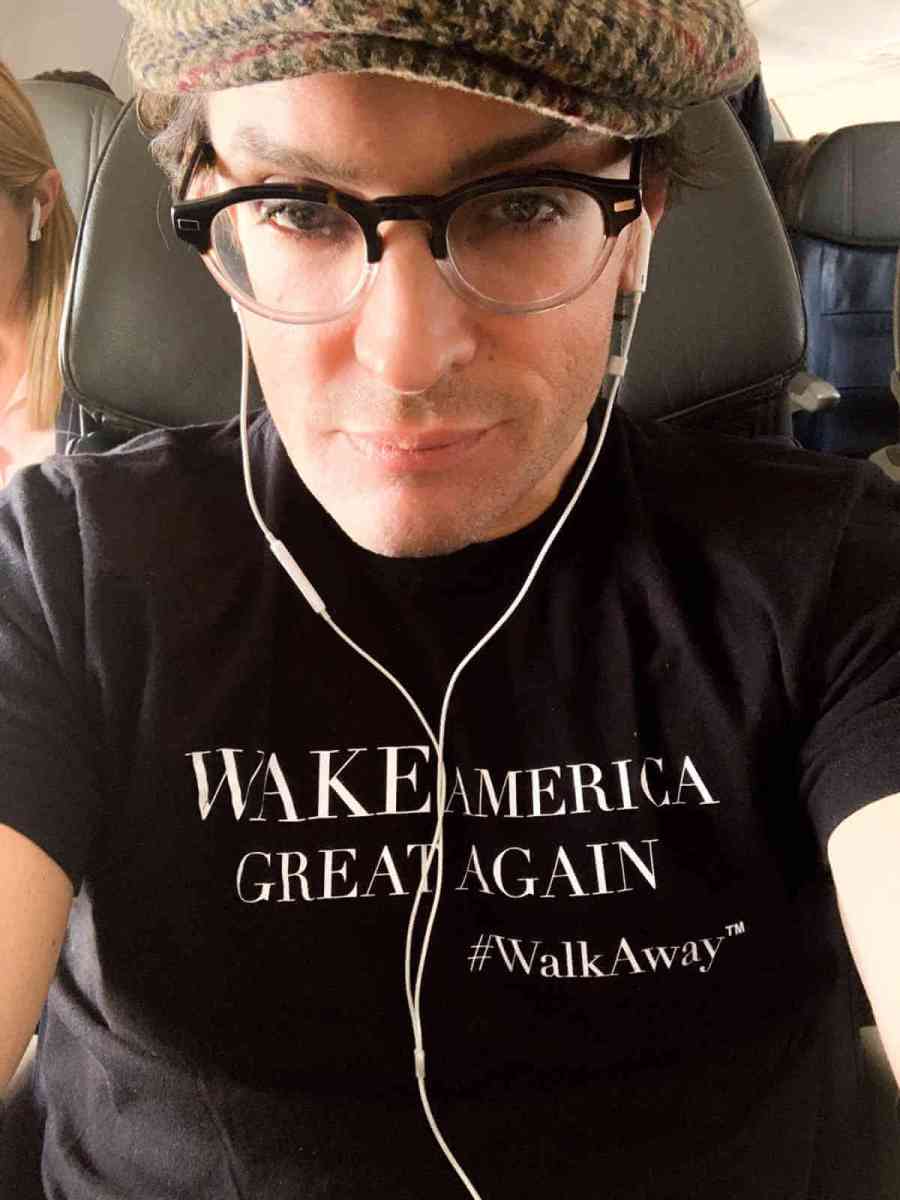

Brandon Straka, who is gay and became a celebrity when he founded the #WalkAway Campaign last year to urge people to abandon the Democratic Party, booked a room at The Center this past March and paid a $650 fee.

The town hall was slated to occur on March 28 and would have featured Straka, Blaire White, Mike Harlow, and Rob Smith. Straka most recently was among the opening speakers at an August 1 rally for Donald Trump’s reelection campaign in Cincinnati, while White, who is transgender, and Harlow, who is gay, have established presences on social media. Smith is best known for opposing the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy that barred LGBTQ people from serving in the military.

Their politics range from libertarian to center-right to conservative. Following a community outcry, which included the distribution of an open letter that criticized the town hall organizers, The Center canceled the event and refunded the $650 fee.

Straka, White, Harlow, and the campaign are the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, which was filed in June. They sued The Center and its executive director, Glennda Testone, as well as Gabriel Farofaldane, who is on staff there. Jason Rosenberg and Gordon Beeferman were among the early supporters of the effort to bar the group and they are also named as defendants. Loftus represents The Center, Testone, and Farofaldane. Rosenberg and Beeferman are represented by J. Remy Green, a partner at Cohen Green.

The lawsuit charges the defendants with cyberbullying, defamation, and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, which is barred by city and state laws. Loftus wrote that the plaintiffs did not support their allegations.

“Plaintiffs fail to allege any facts that connect their respective sexual orientations and gender identities to the decision by The LGBT Community Center to cancel the plaintiffs’ event,” he wrote. “In fact, the Center’s statement regarding the cancelation of the event clearly lists the reason for the event’s cancelation.”

Loftus noted that if the court assumes all the facts asserted in the complaint are true, which it is required to do when weighing a motion to dismiss, “the allegations evidence discrimination based upon plaintiffs’ political beliefs, as opposed to their sexual orientation and gender identity.” Political beliefs are not a protected class in the city and state anti-discrimination laws, and The Center can bar them.

Loftus also asserted that his clients did not issue or sign the statement calling for the town hall to be canceled and that The Center’s own statement about why it cancelled the town hall could not be defamatory as defined under the law. He further stated that a single instance of The Center posting its statement on Twitter and on its website could not be construed as cyberbullying as the law defines that. As important, Loftus asserted that the law the plaintiffs are using for the cyberbullying claim does not create a cause of action for a lawsuit.

“Despite plaintiffs’ conclusory allegations that the decision to cancel the event by The LGBT Community Center was discriminatory or that the statement issued by The LGBT Community Center was defamatory, no interpretation of any act or statement made by The LGBT Community Center defendants are actionable under the theories espoused by the plaintiffs,” Loftus wrote.

In separate filings, Green also sought to dismiss the lawsuit and asked the court to sanction the attorneys representing Straka as well as Straka himself and his colleagues for filing a lawsuit that is “frivolous and without merit.” In an August 7 letter to A. Manny Alicandro, one of two attorneys representing Straka and his colleagues, Green wrote that the plaintiffs had offered no facts that supported the lawsuit.

“As filed, the lawsuit fails to state or even gesture at a single legally supportable claim against Gordon Beeferman or Jason Rosenberg,” Green wrote. “The complaint sufficiently identifies one statement [each by] Beeferman and Rosenberg, a tweet that does not mention a single defendant, and an open letter you allege was ‘principally drafted’ and signed by defendant Gordon Beeferman.”

Rosenberg’s tweet was posted on March 19 and appears to be directed at The Center. He wrote, “Like are y’all that desperate for money? This is incredibly egregious that you’d host an event where panelists have used queer slurs and stood behind policies that put the community at great risk. Stand for something. SOMETHING.”

Straka and his colleagues are also public figures as that is legally defined, Green wrote, who collectively have hundreds of thousands of subscribers and followers on their social media platforms. To prove defamation against a public figure, the plaintiffs have to show that the speakers knew their statements about the plaintiffs were false or they acted with reckless disregard as to the truth of the statements. Green filed a lengthy document filled with tweets and social media posts by the plaintiffs that showed that not only did Rosenberg and Beeferman have good reason to believe that what was said about the plaintiffs was true, those statements were true or “substantially true,” Green wrote.

Those social media posts show Straka with Milo Yiannopoulos, who promoted neo-Nazi and white supremacist ideologies when he worked at Breitbart, and Straka appearing on InfoWars, a show by Alex Jones, a leading voice on the alt right. Harlow is seen boasting of appearing with Gavin McInnes, the founder of the Proud Boys. White is shown flashing a white power hand sign, appearing in black face to mock the Black Lives Matter movement, responding to a question about the “migrant crisis” with “gas em,” and writing “if he ain’t Aryan, we ain’t marryin” on Facebook.

The open letter charged the plaintiffs with espousing “white supremacist, transphobic, xenophobic, and otherwise bigoted views that are dangerous to our communities,” associating with people who advance “violently anti-immigrant, racist, sexist, and queerphobic ideologies,” and being “far-right provocateurs” who share responsibility “for incitement to violence against trans people, black people, women, immigrants, Jews, and Muslims, and who publicly associate themselves with prominent, violent members of the ‘Alt Right’ white nationalist movement.”