Tony Kushner talked to Larry Kramer at the New-York Historical Society on Central Park West on June 26. | HOWARD HEYMAN/ NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Larry Kramer didn’t hold back when interviewed by Tony Kushner on June 26 at the New-York Historical Society, a group so staid that it honored Henry Kissinger at a gala last year. Asked about the Supreme Court’s historic ruling striking down the Defense of Marriage Act that morning, the stinging dissent of Justice Antonin Scalia came up.

“Can we hire an assassin?,” Kramer said only half in jest — to nervous laughter from the audience and Kushner, who said, “To quote Richard Nixon, ‘That would be wrong’” — a riff on the disgraced president distancing himself from the very illegal plans he was discussing with aides in meetings he was surreptitiously taping.

At New-York Historical Society, Tony Kushner draws him out

Kramer also said that Rodger McFarlane — his late close friend and one-time lover who was the first executive director of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, which Kramer co-founded — had been a Navy Seal and the two discussed the idea of “doing guerilla stuff” in the fight against AIDS in the early 1990s when the epidemic in the US was at its worst.

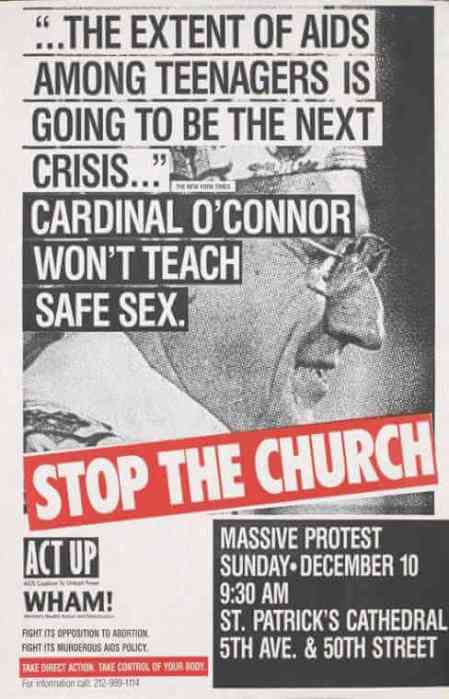

Kramer did co-found the militant ACT UP in 1987, but neither he nor the AIDS activist group ever resorted to violence. When Kushner asked him if he owned a gun, Kramer said, “I’d be scared I’d use it on myself.”

But that doesn’t mean Kramer isn’t deadly serious. He was surprised, he said, that the DOMA ruling was favorable, but he added, “Yesterday we were loathed. Today we’re only hated.”

Kramer had just turned 78 the day before, but has lost none of his fire and is not slowing down. Having picked up a Tony Award last year for the revival of his searing 1985 play “The Normal Heart,” he was given the American Theater Wing’s Isabel Stevenson Award for his humanitarian work at this June’s ceremony. (Kushner is no slouch, either. Having won two Tony Awards and a Pulitzer for “Angels in America” in the 1990s, he got an Oscar nomination earlier this year for his “Lincoln” screenplay and will receive the National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama this week.)

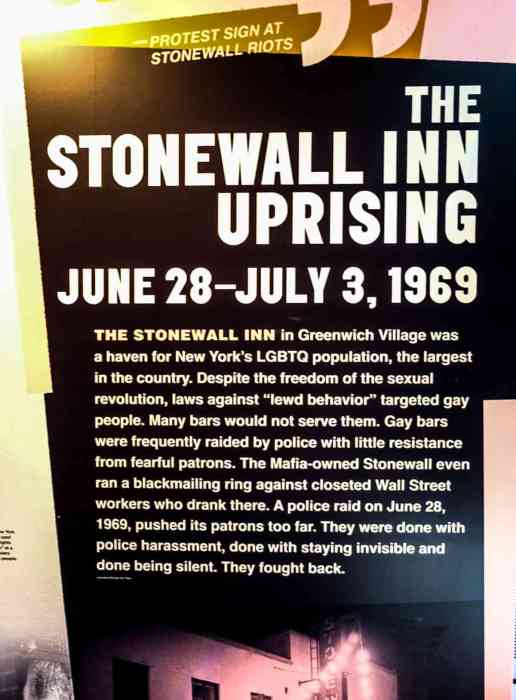

The forum “Larry Kramer and ‘The Normal Heart,’” came amidst the Historical Society’s exhibit “AIDS in New York: The First Five Years” (through September 15). Kramer’s conversation with Kushner also came while the long-awaited film adaptation of “The Normal Heart” is shooting in New York, with Julia Roberts as Dr. Emma Brookner and Mark Ruffalo as Ned Weeks, the Kramer character.

The film is directed by Ryan Murphy of “Glee” fame, whom Kramer termed “the most amazing director I have worked with. He pushed me more and more. He wanted people to see how awful those years were and how awful the disease was.”

He explained, “We’re not filming a play. A play is a play and a movie is a movie.”

While reiterating his disdain for the inaction on AIDS by President Ronald Reagan and New York City’s health commissioner during the epidemic’s earliest years, Dr. David Sencer (“what a sad sack he was”), Kramer reserved special contempt for the late closeted Ed Koch and talked about the efforts he and McFarlane made to get the late Richard Nathan, Koch’s former lover, to tell his story publicly. “He told me in great detail about their love life, but then he chickened out,” Kramer said.

When Kushner noted that Koch finally acknowledged that ACT UP was right, Kramer said, “He was closer to death and wanted to get into heaven.” Koch never acknowledged his own homosexuality.

“I love to write,” Kramer said. “History’s got to be told.”

He explained he got the idea for how to write “The Normal Heart” when he saw David Hare’s “A Map of the World” at Britain’s National Theatre in 1983. “We have no tradition of political theater in this country,” Kramer said, but Hare’s work showed him how it could be done without being agitprop.

Kramer also spoke of his long-awaited novel “The American People,” which is about “how awful we [gay people] have been treated from day one.” He cited John Winthrop, a founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony who pushed through the first law in America making sodomy punishable by death, but also spoke about how Native American tribes could be very accepting of homosexuality.

Kramer is at once enamored and confounded by his own people.

“I don’t call it the gay community,” he said. “We’re the gay population. There are so many different kinds of us. I’ve never been able to figure out why we’re so passive. Blacks are much more active. There were 10,00 gay people in ACT UP out of 20 million of us. You’re not going to fight for your own life? It makes me angry and sad because we’re a wonderful people but that’s our tragic fate.”

Kramer went back into his own literary history as the author of the picaresque novel “Faggots,” which he thought “the boys are going to love,” but was condemned by a reviewer for the Body Politic, a gay publication, who wrote, “You must not read or buy this book!” Kushner noted that his central character, Fred Lemish, was prescient, looking at people dancing and having sex with abandon at a Fire Island club pre-AIDS and thinking about the dangers of infectious diseases. “We’re going to be in a lot of trouble!” Lemish says.

Even as Kramer continues to make trouble with his writing and his activism, he has also mellowed through the love of his longtime partner, David Webster, and the public recognition he is now receiving. Kushner asked him if his book will have a happy ending.

“I don’t know,” Kramer said. “I just remember so much that was terrible and how we were allowed to die. Blacks won all their battles and still are in dreadful shape.”

He added, “It’s not a good time for any kind of activism.”

The cost in lives of loved ones lost to AIDS haunts Kramer, who has lived with HIV for decades.

“I do not know why I was spared,” he said. “I did everything everybody else did.”

When a Bronx doctor who works with poor communities of color that are bearing the brunt of new HIV infections and other health disparities asked him if “there is a solution,” Kramer shot back, “This is not rocket science. You fight back! Doctors have always been cautious about fighting back. You see something wrong and you fight back!”