A new directive from the US Department of Labor is construing three recent Supreme Court rulings as well as two executive orders from President Donald Trump to allow contractors doing business with the federal government to discriminate based on their religious beliefs.

The August 10 directive, which came from Craig E. Leen, the acting director of the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), a Labor Department unit, could undermine the protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity that former President Barack Obama had added to the federal government’s contracting guidelines.

The first court decision Leen cited is Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, the Supreme Court’s June 4 ruling that reversed a lower court decision against a Denver-area baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple.

Significantly, the high court in that decision did not rule that businesses have a general right to deny services to gay couples based on the owners’ religious beliefs. Instead, finessing that issue, the majority found that the lower court’s ruling had to be reversed because the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had exhibited overt hostility to religion in its treatment of baker Jack Phillips, whose refusal to provide his services to the same-sex couples was based on his religious objections to same-sex marriage.

The evidence for this “hostility” boiled down to public statements by two commissioners, one of whom accurately summarized the legal rule that religious beliefs do not excuse a business from complying with state anti-discrimination law, and the other characterizing the use of religion to justify discrimination as “ugly.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy’s decision for the court emphasized that generally businesses do not enjoy a right to discriminate based on the owners’ religious beliefs, and that a “neutral forum” free of overt hostility to religion could enforce the anti-discrimination laws against a religious objector.

Kennedy’s ruling also contended that the Commission had shown additional hostility to religion by dismissing charges brought by a man who complained that several bakers refused his request to make cakes decorated with religiously-based anti-gay scriptural quotes and slogans. The majority clearly believed the Commission was insufficiently evenhanded in dealing with cases involving religious views.

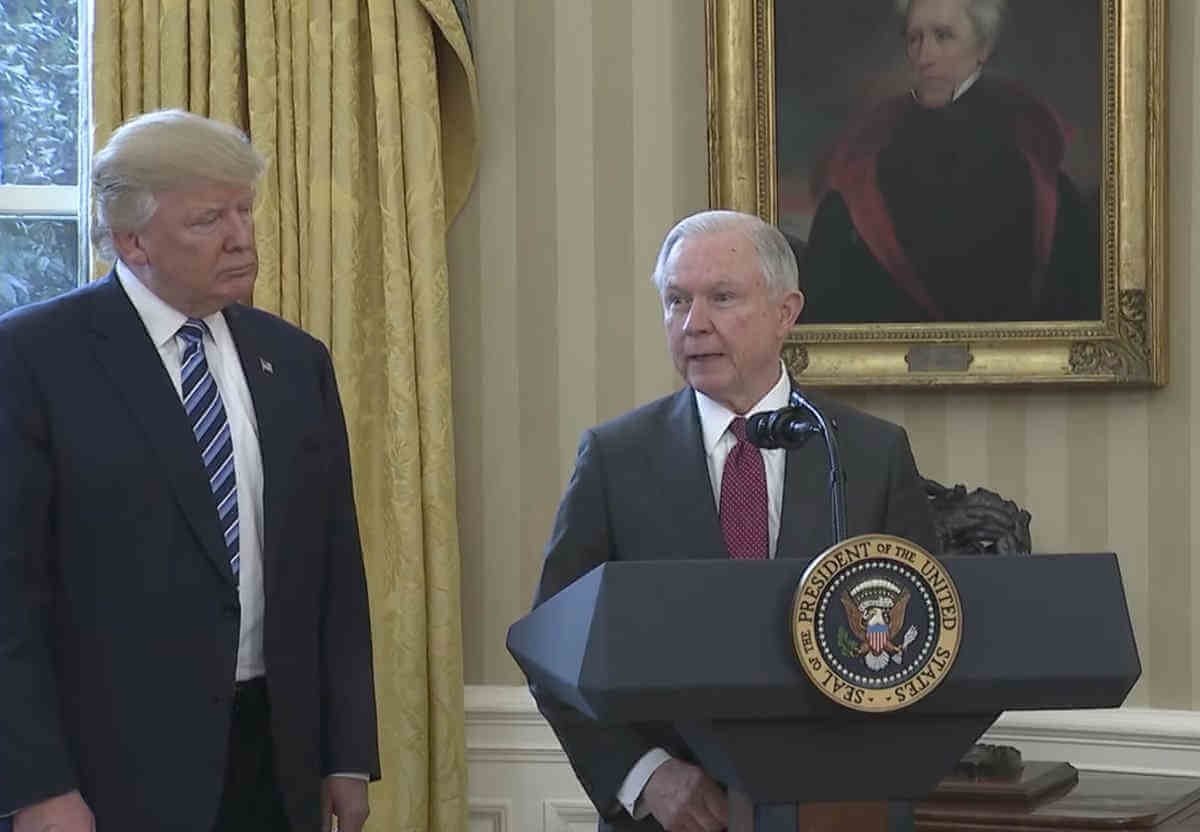

But Leen’s directive, consistent with the two Trump executive orders and a memorandum issued last fall by Attorney General Jeff Sessions, reorients the Masterpiece Cakeshop issue as “discrimination” against religious individuals when they are required to comply with non-discrimination requirements that conflict with their religious beliefs.

“Recent court decisions have addressed the broad freedoms and anti-discrimination protections that must be afforded religion-exercising organizations and individuals under the United States Constitution and federal law,” Leen wrote, painting individuals and businesses who want their religious beliefs to take priority over any contrary legal obligations as “victims.”

Twisting recent Supreme Court opinions to support this assertion, Leen summarized Masterpiece Cakeshop as holding that “the government violates the Free Exercise clause when its decisions are based on hostility to religion or a religious viewpoint.”

Leen summarized the 2017 Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc., v. Comer decision, where the Supreme Court held that a state could not categorically disqualify religious organizations from receiving state funds for non-religious purposes, as meaning that the “government violates the Free Exercise clause when it conditions a generally available public benefit on an entity’s giving up its religious character, unless that condition withstands the strictest scrutiny.”

That case involved Missouri’s denial of funds to a religious school for repaving its playground, based on a state constitutional provision against providing taxpayer money to religious institutions.

Finally, Leen summarized the Supreme Court’s notorious 2014 5-4 ruling in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby as holding that “the Religious Freedom Restoration Act [RFRA] applies to federal regulation of the activities of for-profit closely held corporations.”

Hobby Lobby involved a demand by a business corporation owned by a small group of devout Catholics that it not be required to provide contraception coverage for their employees as required by the Affordable Care Act.

Very few federal contractors subject to federal anti-discrimination rules, which apply only to substantial federal contracts, are “closely held corporations,” so that characterization of RFRA does not seem particularly relevant to the cases where Leen’s directive is likely to be implicated.

Leen also cited Trump’s Executive Order 13831, which states, “The executive branch wants faith-based and community organizations, to the fullest opportunity permitted by law, to compete on a level playing field for grants, contracts, programs, and other Federal funding opportunities,” and Trump’s Executive Order 13798, which says, “It shall be the policy of the executive branch to vigorously enforce Federal law’s robust protections for religious freedom. The Founders envisioned a Nation in which religious voices and views were integral to a vibrant public square, and in which religious people and institutions were free to practice their faith without fear of discrimination or retaliation by the Federal Government. Federal law protects the freedom of Americans and their organizations to exercise religion and participate fully in civic life without undue interference by the Federal Government.”

Sessions’ memorandum ran with these themes, asserting that the government should generally refrain from enforcing federal laws against people and businesses that have religious objections to complying with them.

Leen’s directive, in turn, instructs the OFCCP staff and notifies federal contractors that, in essence, they can discriminate in employing people or providing services under federal contracts if they are doing so based on their religious beliefs.

The Supreme Court arguably opened the door to this kind of thinking in the Hobby Lobby and Trinity Lutheran cases, but it is a stretch to cite Masterpiece Cakeshop for this purpose in light of the mention Justice Kennedy made in his majority opinion of two other cases: Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, a 1968 decision holding that a Southern barbecue restaurant chain could not refuse to serve black customers based on the owner’s religious belief in racial segregation, and Employment Division v. Smith, a 1990 decision holding that people do not enjoy a Free Exercise right to refuse to comply with state laws of general application that are on their face neutral with respect to religion.

Writing for the Supreme Court in the Employment Division case, Justice Antonin Scalia suggested that allowing individuals to claim exemptions from the law based on their individual religious beliefs unless the government could prove that it had a compelling interest was not required by the First Amendment.

“Any society adopting such a system would be courting anarchy, but that danger increases in direct proportion to the society’s diversity of religious beliefs, and its determination to coerce or suppress none of them,” Scalia wrote.

Although the court’s decision in Employment Division was unanimous, it is worth noting that four of the justices concurred in an opinion arguing Scalia had gone too far in his majority opinion in contending the government need not show there was an important government interest that justified burdening an individual’s free exercise of religion — in that case, a Native American denied unemployment benefits when he was fired after flunking his employer’s drug test due to his religious ritual use of peyote.

Enforcing religiously neutral anti-discrimination rules is not “hostility to religion” by the government. It is undertaken to prevent categorical discrimination based on personal characteristics, such as race, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

Notably, the federal laws and regulations that OFCCP is supposed to enforce already do not apply to government contractors that are religious corporations or associations or religious educational institutions, “with respect to the employment of individuals of a particular religion to perform work connected with the carrying on by such corporation, association, educational institution, or society of its activities.”

It should also be noted that Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion for the court in the Hobby Lobby case responded to concerns raised by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent by denying that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act could be invoked as a defense in an employment discrimination case.

How this will all play out if OFCCP refuses to hold contractors to their non-discrimination requirements in situations involving LGBTQ victims of religiously-motivated discrimination is yet to be seen, but the portents are not good in light of Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, where, if confirmed, he would join the conservative majority in place of Justice Kennedy.

In this context, it is particularly troubling that Justice Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s first Supreme Court nominee, in his concurring opinion in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case, implied that the court should reconsider its holding in Employment Division v. Smith.

In response to Leen’s directive, the National Center for Transgender Equality warned of a “broad license to discriminate,” while noting that the Department of Labor, at the same time, removed language from its website about nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ people and the limited scope of allowable religious exemptions.

“This is an attempt to encourage businesses to take taxpayer dollars and then fire people for being transgender,” Harper Jean Tobin, the group’s director of policy, said in a written release. “Religious organizations have ample protections under federal law, but they are not allowed to use federal money to discriminate against people. The language of this directive is so broad and so vague because it is part of a long line of attempts by this administration to sow confusion and encourage any employer to act on their worst prejudices. No employer should be allowed to use taxpayer dollars to fire someone because of who they are.”