Doubtless you’ve been reading a lot about Kevin Spacey lately. The chickens — or in this case chickenhawks — have come home to roost for the two-time Academy Award-winning actor whose penchant for “barely legal” youths has been well-known for decades and completely tolerated by an entertainment industry that will stand for anything insofar as the person responsible has “market value” — something that may have slipped away for Spacey once and for all. But Spacey’s modus operandi — slipping his hand down the pants of lads he’s taken a fancy to reminded me of a sexual importunist who crossed my path 55 years ago.

One afternoon in 1964, I was sitting downstairs at the Museum of Modern Art waiting for the doors to open for a film I was seeing. I can’t recall the title of the film, but I well recall the afternoon’s most consequential event. I met The Sugar Plum Fairy.

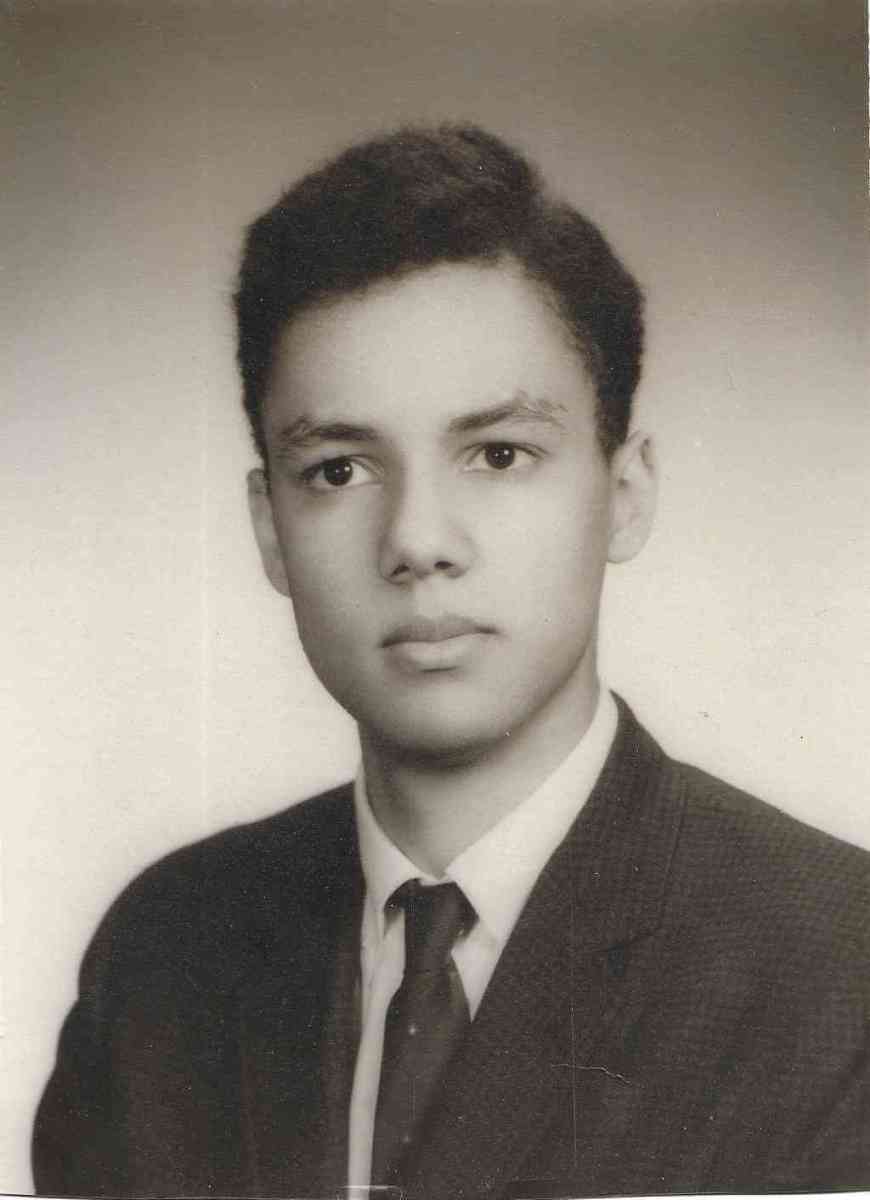

I was perusing the latest issue of Sight & Sound and wasn’t waiting for anyone to join me. Lost in my magazine, I was somewhat surprised when a dashingly good-looking and very well-dressed man in his late 20s or early 30s began to chat up my 17-year-old self. It was all casual and friendly at first, but in no time his tone changed as he asked me to forget about the movie and come back to his apartment. I wasn’t sexually inexperienced, but what action I’d enjoyed had always been with friends. Suddenly the prospect of having sex with a total stranger opened up to me. I was flattered, then intrigued, and at the last ever-so-slightly frightened. Happily, I had the excuse of the movie being something I wanted to see as reason to turn him down. He took it well. He did, though, hang about a bit, even going into the auditorium and sitting a row or so away, clearly in my line of sight, in the hope I might change my mind. When he realized I wasn’t going to, he left.

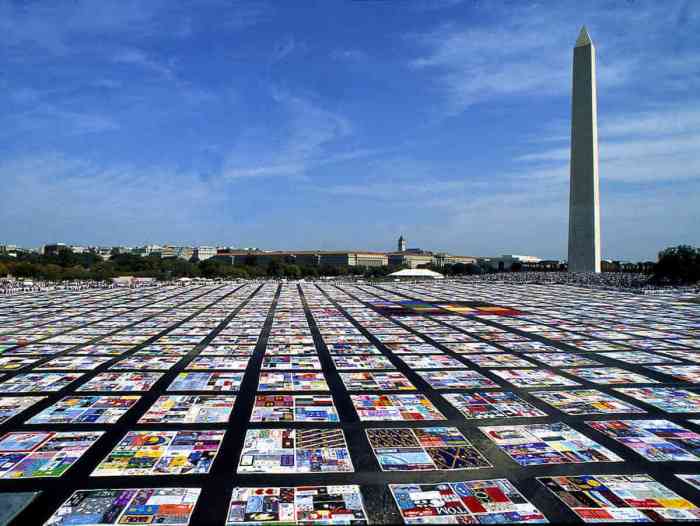

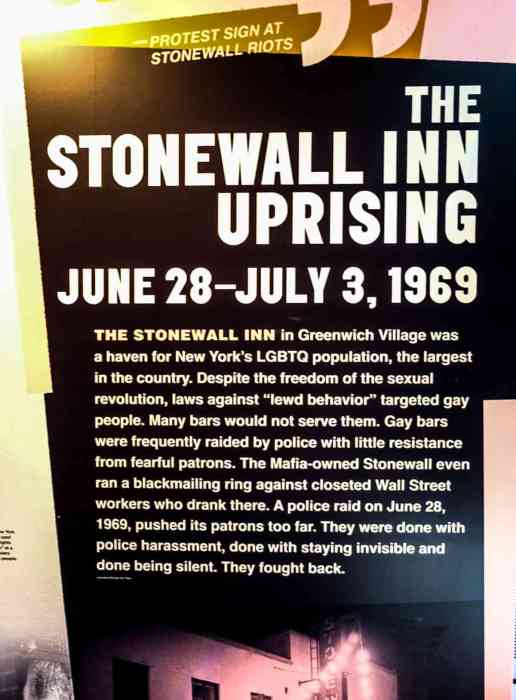

“You turned down The Plum!,” Dorothy Dean exclaimed with considerable astonishment when I told her about the incident a decade later. Dorothy, the most legendary of all fag hags (“Fruit fly — I prefer fruit fly,” she would say) in pre-Stonewall New York, a perpetual presence at Andy Warhol’s Silver Factory and the overseer of his table at Max’s Kansas City, had named my would-be seducer the Sugar Plum Fairy many years before.

I discovered his connection to Dorothy the year after I met him, when I saw Warhol’s “My Hustler.” Written by Chuck Wein and starring Ed Hood, a blond number dubbed “Paul America,” Chuck’s writing pal Genevieve Charbon, and — ever so briefly— Dorothy. Its semi-action unfolds on Fire Island where Ed, having purchased the services of Paul through “Dial-A-Hustler,” observes him sunning himself on the beach while chatting to Genevieve and her pal, The Plum — whose real name was J. D. McDermott. Though Ed has paid for Paul’s services, J.D. contrives to win him away from Ed in a lengthy scene where J.D. and Paul, quite naked, primp in front of a bathroom mirror while sizing each other up both verbally and optically. The lines J.D. throws to Paul to reel him in bore a striking similarity to the ones he’d used on me the year before. Being a Warhol film, there’s no dramatic resolution, just Dorothy as a kind of Deus ex Machina. She enters the bathroom and makes a play for Paul to come with her instead of Ed or J.D.

Outside of a brief turn as a cop (of all things) in “Vinyl” — Andy’s “sampling” of Anthony Burgess’ novel “A Clockwork Orange” made with the aid of Ronnie Tavel that same year (in which Edie Sedgwick makes her film debut) — that was it for The Plum’s movie career. He’d had a social career some years before when he was the kept boy of a closeted investment banker named Harvey Milk. As we all know Harvey, in the grand ‘60s tradition, turned on, tuned in, and dropped out, kicking over all traces of respectability, leaving New York and heading for San Francisco to achieve gay political immortality.

The Plum didn’t end very well, defenestrating himself sometime in the ‘80s, we surmise. (Something of a Warhol tradition: vide Freddie Herko and Andrea Feldman.) He has, however stayed with us perpetuity thanks to the great Lou Reed:

“Sugar Plum Fairy came and hit the streets

Looking for soul food and a place to eat

Went to the Apollo

You should have seen him go go go

They said, “Hey sugar, take a walk on the wild side”

I said, “Hey babe, take a walk on the wild side” alright, huh…”

So now I know why The Plum chose me. He was a “dinge queen.” I seriously doubt that Kevin Spacey will be saluted in song. As for how he will end, his career has taken a header ever since October 29, 2017, when actor Anthony Rapp revealed that Spacey made something more than a pass at him in 1986, when Rapp was 14 and Spacey 26. Rapp, long an out gay adult, had first shared this story in a 2001 interview with The Advocate, but Spacey’s name was redacted from publication to avoid legal disputes — a common practice throughout the media in those days.

In response to Rapp’s second, public revelation, Spacey tweeted he did not remember the encounter, but that he owed the younger man “the sincerest apology for what would have been deeply inappropriate drunken behavior.”

As we quickly learned he has tons more to apologize for.

To begin at the beginning of his sexual notoriety, I trust many will recall an incident during the shoot of “The Usual Suspects” in 1995: Spacey was called to the set and when he didn’t come right away, director Bryan Singer went to his trailer and found him doing the horizontal mambo with Singer’s boytoy du jour. The news of this went all over the net in nanoseconds. On Datalounge, the most delicious gay gossip site in cyberspace, it was under discussion for months afterwards. But what’s said in Datalounge stays in Datalounge, and Spacey’s performance in “The Usual Suspects” won him his first Oscar.

A short time later, Singer, who loves to walk around LA, ran into me up on Sunset Boulevard across the street from the DGA Theater. I had never met him before, but he clearly knew who I was because he came up to me and said, “I want you to know Kevin and I are friends and the kid is no longer in my life.” Wow, the director reads Datalounge! Singer’s own dalliances with barely legal youths and his professional unreliability as a whole (he walks off sets whenever he feels like it) got him thrown off his most recent film, “Bohemian Rhapsody,” halfway through the shoot. Dexter Fletcher took over the reins, but only Singer was afforded official directorial credit. Still, Singer was conspicuous by his absence at this year’s Golden Globes when the film and its star, Rami Malek, won top prizes. Those who accepted the award for the film never uttered his name. Where Singer’s career goes from here on in is anyone’s guess. As for Spacey, he has legal matters on his plate rather than movie offers.

After Rapp’s revelation, 15 others came forward alleging abuse, including journalist Heather Unruh, who said that Spacey sexually assaulted her son; Norwegian author Ari Behn; filmmaker Tony Montana; actor Robert Cavozos; actor Richard Dreyfuss’s son Harry; and eight crew members from Spacey’s former series “House of Cards.” In the midst of the allegations, filming was suspended on the series’ sixth and final season, which was then shortened from 13 episodes to eight, with Spacey removed from the cast and his role as executive producer.

Meanwhile, The Guardian was contacted by “a number of people” who worked at the Old Vic — where Spacey was artistic director from 2003 to 2013 — and alleged he “groped and behaved in an inappropriate way with young men.” On November 16, 2017, the Old Vic confirmed it had received 20 testimonies of alleged inappropriate behavior by Spacey, with three persons stating they had contacted the police.

The following month, Spacey’s “Usual Suspects” co-star Gabriel Byrne revealed that production on that film was shut down for two days because Spacey made unwanted sexual advances toward a younger actor.

Spacey was originally cast as financier J. Paul Getty in Ridley Scott’s 2017 “All The Money in The World” about the kidnapping of Getty’s son, but because of the scandal was replaced by Christopher Plummer, even though Spacey had already filmed some of his scenes. That fall, the International Academy of Television Arts and Sciences reversed its decision to honor Spacey with its International Emmy Founders Award.

Clearly, the jig was up. On November 1, 2017, Spacey stated he would be seeking “evaluation and treatment” for his behavior. By then he had officially come out, despite years of denying this truth and loudly proclaiming his love for his female personal assistant each time he won an Oscar.

The charade had gone on for far too long, and everyone knew it — even before his most recent scandals broke.

Who can forget “Kevin Spacey Has A Secret,” the 1997 Esquire cover story by Tom Junod. Written on the occasion of Spacey starring in Clint Eastwood’s film adaptation of John Berendt’s novel “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil,” in which he played a gay man — a very suave one, quite unlike himself — Junod’s article hinted about Spacey’s gayness without coming out and declaring it.

The day after Spacey said he was seeking help, his publicist, Staci Wolfe, and talent agency, CAA, ended their relationships with him. In July 2018, three more allegations of sexual assault against Spacey were revealed by Scotland Yard, bringing the total number of open investigations in the UK to six.

In September 2018, a lawsuit filed at Los Angeles Superior Court claimed that Spacey sexually assaulted an unnamed masseur at a house in Malibu in October 2016. Last month, Spacey was charged with sexually assaulting former Boston news anchor Heather Unruh’s son in Nantucket in July 2016. On January 7, Spacey pleaded not guilty in that case. The case is going forward. Spacey isn’t.

A Gore Vidal biopic, “Gore,” starring Spacey was set to be distributed by Netflix, but was canceled, and the company went on to sever all ties with him.

Perhaps someone will want to triple feature it with Louis CK’s similarly canceled “I Love You Daddy” and Woody Allen’s discarded “A Rainy Day in New York.” The careers of all three of these once formidable performers appear as dead as The Sugar Plum Fairy. No one wants to take a walk on their wild sides.