Kerry Kennedy, president of the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights and a grand marshal at the March 1 St. Pat's for All Parade in Sunnyside, Queens. | DONNA ACETO

Kerry Kennedy minced no words in characterizing the longstanding policy of Manhattan’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade in excluding openly LGBT participants. The president of the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights, named for her slain father, Kennedy recalled a meeting a year or so ago with LGBT leaders in Uganda, including Frank Mugisha, whom her group honored in 2011. After the meeting broke up, two transgender activists were apprehended by authorities, and Kennedy and her teenage daughter, Cara, spent the night at a police station working to win their release.

“Uganda is a country with 37 million people,” she said. “And there are 30 people in the LGBTQI movement and three willing to get up in front of a microphone.” Then, pivoting to the Fifth Avenue St. Patrick’s policy, Kennedy said, “What’s happening here in New York — this is not a joke. What the Manhattan St. Patrick’s parade is saying is, ‘We stand united with you in your hatred of gays. It is okay to discriminate against gay people.’”

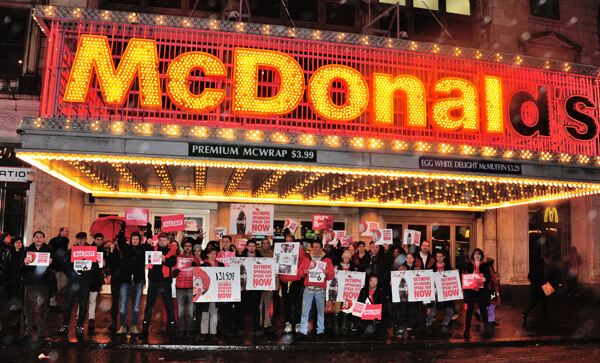

As a member of the nation’s most prominent Irish-American political family, Kennedy’s words carry bite. And her role as a grand marshal in this year’s St. Pat’s for All Parade in Queens — an inclusive event founded 16 years ago in reaction to the ban in Manhattan — has particular resonance. “I was very touched and thrilled to be part of the parade in Queens,” she said. “It is not about tolerance, it is about celebration. I had 10 siblings, and I never wanted to hear, ‘I know she is irritating, but try to tolerate her.’”

Grand marshal in Queens, human rights advocate scorches Fifth Avenue parade organizers

The Fifth Avenue parade organizers, Kennedy asserted, are out of step with the Irish and Irish-American communities, but also betray their own heritage. “I think it is anachronistic and I think it is particularly unfortunate for the Irish-American community,” she said. “I remember as a child when my grandmother, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy, used to take me up to the attic and show me the newspaper clippings that read, ‘No Irish Need Apply.’ We were oppressed for hundreds of years. We, of all people, should be sensitive to this.”

Kennedy shared the view of many LGBT activists that the inclusion of a gay group from the Fifth Avenue parade’s broadcast sponsor, NBC, was not enough to end its exclusionary legacy, but predicted it could prove to be a beneficial “wedge. I don’t think this can continue for too long.” She noted that the Irish consul general in New York, Barbara Jones, was hosting a reception for Queens’ inclusionary event several evenings before that March 1 parade.

A number of leading political observers, including the New York Times’ Thomas Friedman, have recently raised concerns about the reversal of fortune the world’s democracies — and by implication, the quest for human rights — have suffered in recent years. Kennedy, however, who has worked in the human rights field since the 1980s, sounded undaunted, saying, “I actually am enormously optimistic in terms of progress on human rights.”

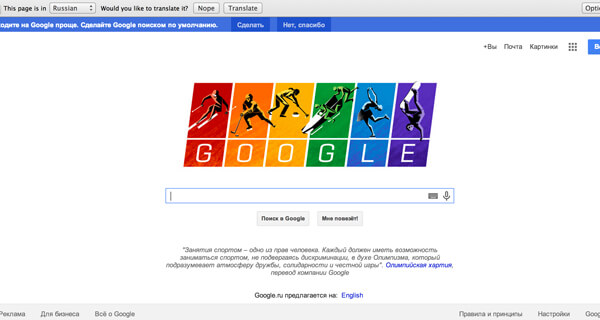

Noting that 30 years ago, South America was full of dictatorships and South Africa was an apartheid state, she pointed to “non-governmental organizations working in every country today to create change and demand that their government be responsive.” Awareness of women’s rights as human rights, Kennedy said, exploded after Hillary Clinton, while first lady, made that argument at the 1995 Beijing women’s conference. “Millions of women have been subjected to genital mutilation,” she acknowledged, “but today we know about it.” Without downplaying the horrors of the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram in Nigeria or of the anti-gay regimes in Uganda and Russia, Kennedy insisted “the world now has much more sophisticated ways of addressing human rights violations.”

Asked her view of US leadership on human rights, she said, “I am an activist, so I have all sorts of complaints about our government. That’s my job — not to complain, but to push for changes.” Then, in a formulation not altogether surprising from a Kennedy, she added, “ I think the question is not, ‘How is the Obama administration doing?’ The question is, ‘What if you had a member of the opposite party in that job? If you had Romney and you’re talking about gay rights?’ Because that’s your choice.”