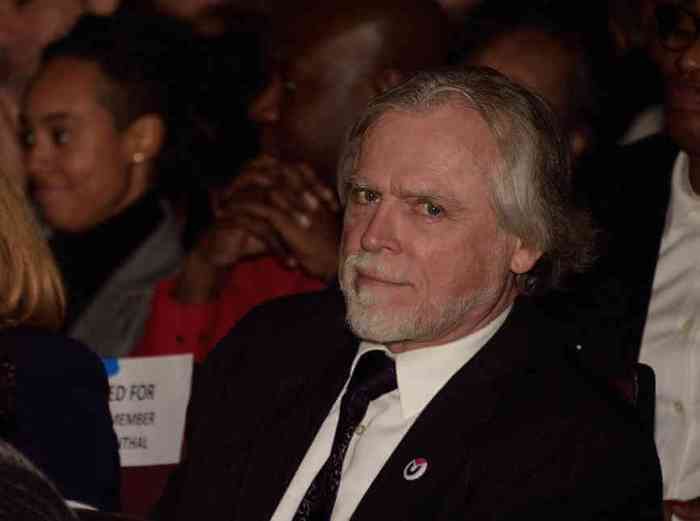

Dr. Demetre Daskalakis. | DONNA ACETO

The Plan to End AIDS could cost tens of millions of dollars initially, with those costs first increasing then declining if the plan meets its target of reducing new HIV infections in New York State from its current roughly 3,000 a year to 750 by 2020.

“Fifty million dollars would get you well into the game,” said Charles King, chief executive officer at Housing Works, an AIDS group, referring to the plan’s first-year price tag. King co-chairs the 63-member task force that is drafting the plan.

In June, Governor Andrew Cuomo endorsed the plan, which will use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and treatment as prevention (TasP) to prevent new HIV infections. With a nod to the plan’s reliance on costly anti-HIV drugs for PrEP, PEP, and TasP, the first act by the Cuomo administration was to negotiate reduced drug prices with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Plan to End AIDS involves tens of millions of dollars, though private insurance, government funds split not now known

PrEP gives anti-HIV drugs to uninfected people to prevent them from becoming infected. It is highly effective when taken daily. PEP is a 28-day course of anti-HIV drugs that prevents infection in someone with a recent exposure. TasP keeps infected people healthy and it reduces the amount of virus in their bodies so they cannot infect others. Like the interventions for HIV-negative people, TasP also requires adherence to a dosing schedule.

In addition to reducing new infections, advocates also hope to create a single point of access to entitlement programs for people who are HIV-positive. Such an effort would probably be administered by county or city governments and would sign up HIV-positive people for Medicaid, food stamps, and rental and transportation assistance at one agency. Some data supports the view that such benefits make it easier for HIV-positive people to adhere to anti-HIV drugs, which is necessary for TasP to be successful.

The total increase in costs under New York’s plan is unknown and the new dollars needed will not come exclusively from the government, but both the state and the city will have to find some new funds.

In 2007, AIDS groups unsuccessfully sought to open the city’s HIV/ AIDS Services Administration (HASA), which is akin to the single point of access proposal, to all HIV-positive New Yorkers and not just those with an AIDS diagnosis. Advocates put the cost of that at $68 million annually and the City Council estimated it would cost $75 to $100 million annually. The number of new clients added under the single point of access proposal would likely be lower than the 10,000 who were expected to enroll at HASA under the 2007 proposal.

Medicaid, the health insurance plan for low income people that is jointly funded by the state and federal governments, is already paying for PrEP for roughly 3,100 New Yorkers and private insurance is likely paying for PrEP for others. Medicaid and private insurers also cover PEP and TasP. The costs borne by Medicaid and private insurance will certainly increase.

In order to cut new infections, the plan will have to get very high numbers of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men on PrEP as well as a greater share of positive men on treatment to suppress their viral load. In 2012, the latest year for which the state has data, 95 percent of the state’s 3,316 new HIV diagnoses were in New York City and 55 percent of the city diagnoses were among men who have sex with men. The rate of new HIV diagnoses among New York City gay and bisexual men has remained high and stable for 13 years.

Currently, an estimated 51 percent of HIV-positive people in the state are virally suppressed.

“We do know that we have to double the number of people who are in treatment and virally suppressed,” King said.

In addition to the 3,100 Medicaid recipients on PrEP in New York, Gilead Sciences — the company that makes Truvada, the only drug approved for PrEP — estimates that 3,253 “unique individuals” nationally began PrEP between January 1, 2012 and March 31, 2014. The rate at which people are starting PrEP appears to be increasing, according to the Gilead data.

State Senator Brad Hoylman speaking at the World AIDS Day event at the Apollo Theater. | DONNA ACETO

One indicator of the cost of just the PrEP portion of the state’s plan comes from the state health department in Washington. It launched its PrEP Drug Assistance Program in April. For uninsured enrollees, it pays for Truvada and the quarterly testing needed to monitor for side effects. For insured enrollees, the program pays deductibles and co-pay fees. It will cover 200 enrollees at a cost of $2 million annually, though as the program is finding that most enrollees have insurance, it could cover 300 enrollees at the same cost. With 300 enrollees, that is just under $6,700 per person per year.

To get the thousands of New York City gay and bisexual men on PrEP needed to significantly reduce new HIV infections would cost tens of millions of dollars, though those costs would be shared by the state and private insurers. Gilead also offers Truvada at a reduced cost to qualified individuals.

The state health department did not respond to an email seeking comment about the cost of the plan.

At a World AIDS Day event at the Apollo Theater, out gay State Senator Brad Hoylman, who represents the West Side, noted the importance of money.

“If we provide the funding, if we have the political will, of course we can end the epidemic,” he said at the December 1 event.

In a follow up conversation, he was more careful.

“We need to fully fund the task force and its recommendations,” Hoylman said. “I’ll reserve comment until we see what those recommendations are… [The plan] is an important blueprint for legislators and then we can start talking about numbers in the budget.”