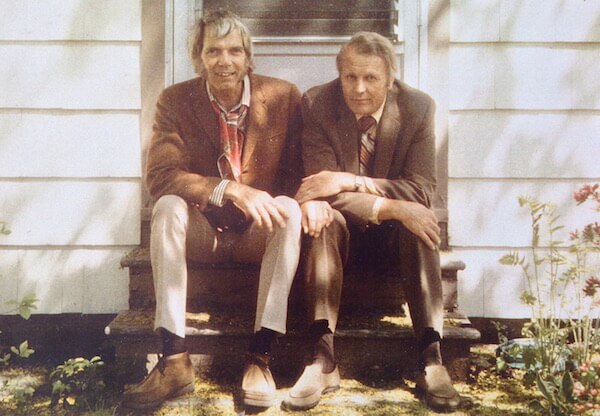

Early lesbian and gay activists Barbara Gittings and Frank Kameny appear with Dr. John Fryer, disguised with a Richard Nixon mask as Dr. H. Anonymous, before the 1973 American Psychiatric Association meeting that voted to eliminate homosexuality as a mental illness as designated in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. | KAY TOBIN LAHUSEN/ NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY DIGITAL GALLERY

Ain Gordon’s play, “217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous,” running next month at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, concerns the work of Dr. John Fryer (1937-2003) that culminated in the removal of homosexuality from the DSM (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) after his riveting testimony at the annual American Psychiatric Association (APA) meeting in 1972. Back then, an openly gay psychiatrist could lose his medical license, so Fryer, who had already been fired from the University of Pennsylvania for being gay, testified under a pseudonym (Dr. H. Anonymous), wearing a rubber Richard Nixon mask and using a voice modulator. His opening words were, “I am a homosexual. I am a scientist.”

Gordon learned of Fryer when he came across 217 boxes filled with his papers, ferreted away in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Center City. The May 3-11 run of the play will coincide with this year’s APA meeting occurring steps away at the Javits Convention Center from May 5 to 9.

Multi-award-winning actress Laura Esterman met me in a Chelsea diner to talk about her involvement in this important dramatic reveal — commemorating the 45th anniversary of homosexuality’s redesgnation — about this too-little known, major gay hero.

IN THE NOH: Ain Gordon play explores Dr. John Fryer’s anonymous work; Marilyn Maye & Grace Jones

“I love this play. We originally did it in Philly in 2016. I’ve worked with Ain before, and he’s great. His father is choreographer David Gordon and his mother is Valda Setterfield, the dancer, and we were able to use their sudio to rehearse in.

“Fryer is not very well-known, considering what he did. I play Katherine M. Luder, his longtime secretary who was with him 25 years. Besides his practice, he taught at Temple University while having to stay closeted and helped a lot of people who came to him in secret, that’s what my third of the play is about. This is not some sad play about lonely characters finding each other. He had partners, and she had her own life, a working relationship that worked. It consists of three monologues, and I am preceded by his gay activist friend Alfred A. Gross (Derek Lucci), and followed by Ken Marks, who plays his father, Ercel.”

Fryer, himself, is not actually portrayed, Esterman explained, “and I think that’s more interesting. The whole evening s very compact, with a lot of humor. Ain’s specialty is writing about historical characters that aren’t very well known, and the premise is that it’s a series of conversations between a historical tour guide and these three characters.”

Just about a year ago, I met Esterman, an actress I’ve always admired, at the annual New Dramatists’ Luncheon at the Marriott Times Square and was immediately drawn to her down-to-earth friendliness and realistic attitude about the ups and downs of a theatrical career. This year has been a good one for her, for, besides this play, she just finished appearing in David Rabe’s “Good for Otto”, playing the mother of a hoarder (Kiki & Herb’s Kenny Mellman). She received her greatest acclaim for the play “Marvin’s Room,” which in 1991, won a slew of awards and really thrust her into the media spotlight.

Of that time she recalls, “It was wonderful, although it was sad that [playwright] Scott McPherson was sick. But we knew when it was happening that it was special and we’d better enjoy it. The real joy was in creating that part. A lot of things you commit to don’t work out, but something about that one clicked. In the wrong hands, it would not have worked. It’s so delicate and could have just turned into melodrama.

“Of course, I didn’t see the recent revival of it, or even read the reviews. I couldn’t, it was too painful for me, and thinking about it made me sad. Scott is dead, and it’s very hard to find the right tone for it. I didn’t want to see someone else do it. I couldn’t handle it.”

Esterman was born in Brooklyn, but her parents moved the family to Lawrence, Long Island, when she was very young.

“Even as a child, I’d say, ‘Why do we have to live here? Why can’t we live in New York?’ I don’t know where I got the acting thing from but as a child I was always putting on shows. My parents would take me to Broadway shows and the opera and enrolled me with music teachers, as I played the piano.”

A production of “Great Expectations” needed a little girl to play Estella: “You know, ‘What’s your name, boy?’ I could do the British accent, thanks to a very cultured uncle of mine, but it was always inside me, this need, something I couldn’t control. I don’t think most actors would actually choose this profession unless this was so, otherwise, why would you want to? It’s a hard life, with very little glamour.

“Actually there is some glamour and it is fun to work with good directors and actors. I love directing, myself. It’s such a relief to be able to just watch from the back with a drink and not have to be on stage.”

Esterman got her training at the prestigious LAMDA academy in London.

“I loved it there. It was the swinging 1960s, unbelievable to be hanging out, having affairs with these gorgeous men with accents. Being a Jewess was exotic to them, not a religious thing, but exotic, like a goddess, a belly dancer. They still have a different viewpoint there, less overt and therefore healthier, I think. But now the world has changed so much, so who knows?”

She returned to America and did regional theater everywhere for two years, playing all the classical roles she was trained for. Her Broadway debut came with Saroyan’s “The Time of Your Life,” followed by “Waltz of The Toreadors,” starring Eli Wallach and Anne Jackson: “They were fabulous, treated us all wonderfully and I became real friendly with them. I was bored, playing a small part, but I understudied the older woman part, with whom Eli fell in love, which was fun. Victor Garber was in it, too, and he is so witty, with a great sense of making fun of himself, you could fall in love with him. So much fun, the coolest guy!”

Esterman has the distinction of being in one of Neil Simon’s rare bombs, “God’s Favorite”: “Oh God, I played the daughter of Vincent Gardenia, and my bathrobe was always open so he was always telling me to close it. It was based on the book of Job, and not very good. Charles Nelson Reilly was in it — a great guy who adopted me and took me to Sardi’s.

“Weirdly, it was directed by Michael Bennett. I was a little girl, all I could think was ‘A Chorus Line?’ We all kind of knew we were in trouble, the play did not work, nobody’s fault. Neil Simon was very sweet: he’d come and laugh at his own lines, but when it wasn’t successful, he disappeared, which is what happens.”

Esterman is happily married, for years, to Eric Hart, who owns the Cape Cinema movie house — which hosted the first ever showing of “The Wizard of Oz” in 1939 — in Dennis, Massachusetts, where she blissfully summers.

“We were introduced by the propmaster working on ‘Tamara,’ which I did in the Armory. I got really lucky because I’m pretty neurotic, and he’s not always the easiest, but I’m here working and he’s on the Cape a lot. So we’re not together all the time, and it’s hard being apart. But I always look forward to seeing him. It’s good, it works out, and I can’t wait for the weather to improve, just be on the beach with a drink and relax.”

Two music legends recently gave me big joy. Marilyn Maye just celebrated her 90th birthday, and I caught her commemorative gig at Feinstein’s 54 Below on April 22. A packed house of Maye-niacs made it one huge lovefest as this indestructible vocal force of nature glided through the Great American Songbook, bringing distinction to everything she sang, as well as the kind of magisterial, deep humor only a supremely confident mistress of her metier can muster. During her glowing Cole Porter medley, she opened “I Get a Kick Out of You,” with the words, “My story is much too sad to be told,” and proceeded to trudge sadly offstage, into the darkness, her shoulders hunched with gloom, before getting her laughs and returning with a more familiar radiant smile on her face to finish the ditty. Loved that, love her!

Another sold-out fan orgy occurred with Grace Jones’ now-historic appearance on April 13 at the New York Times Center for a Times Talk that began with a surprise musical performance.

Mounting her trademark staircase, she sang a throbbingly funky “Nightclubbing,” clad in sequinned derby, tailored jacket, stiletto heels — and that was about it. When she got to the top, she decided to jump some six feet back onto the stage. Those heels gave way and she was sprawled, flat on her back, for a small eternity as everyone wondered if she was alive.

But she eventually righted herself to make a relatively graceful exit, and, after an understandable delay, returned to be interviewed by already long-suffering reporter Melena Ryzik.

The outrage continued, with her gleefully highjacking the night, answering Ryzik’s repeated inquiries as to her noted male-female androgyny with statements like “I have a very big clitoris” and, when asked how her male side manifests itself, she replied, “You’ll know when I penetrate you.” Ryzik’s face, as she finally left the stage after the interview, looked like she’d just experienced rough sex for the very first time.

217 BOXES OF DR. HENRY ANONYMOUS | Baryshnikov Arts Center, Jerome Robbins Theater, 450 W. 37th St. | May 3-11 at 7:30 p.m. | $40 at 217boxes.com