January is the Janus month where we look forward to the new year and back at the old. In the opera world, 2013 had a lot of distressing developments, a few solid triumphs, but also a lingering sense of instability and a deadening sense of artistic compromise. Companies for the most part aren’t taking big artistic or financial risks.

One company that is expanding its horizons in every direction is Gotham Chamber Opera under the direction of Neal Goren. The company explored the French baroque repertory with a staged production of Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s “La descente d’Orphée aux Enfers” (1686), which opened on New Year’s Day. This was part of Trinity Wall Street’s “Twelfth Night Festival” curated by conductor, composer, and baroque specialist Julian Wachner. It was performed on the altar and in the nave of St. Paul’s Chapel.

The opera in two acts is just over an hour long and ends with Orpheus leading Eurydice out of the underworld. It is thought there was a planned or lost third act depicting the tragic denouement but it has not survived.

Gotham Chamber Opera on the rise; new casts for Met “Onegin,” “Rigoletto” revivals

Charpentier’s setting is very much in the gentle pastoral vein throughout. The wildness of Gluck’s “Dance of the Furies” or the tragic starkness of the Messagera’s monologue in the Monteverdi are absent. Everything is lyrically beautiful but somewhat lacking in dramatic impact. Typical of the early French baroque, there are long dance sequences and no elaborate vocal showpieces. Charpentier’s Orphée gets a few short lamenting ariosos but no showstopper arias. All this puts Charpentier’s version of the myth at a disadvantage in comparison with the many other operatic settings.

Andrew Eggert’s staging utilized St. Paul’s upper balcony loft and twisting staircase down to the altar level to descend to or ascend from the nether regions. A technical malfunction on opening night limited the use of projections on scrims erected around the playing area –– what remained was more than adequate. Compared with the sophistication of the European directors who staged the Les Arts Florissants productions at BAM, the direction and costumes looked naïve and literal.

Doug Elkins’ basic choreography was performed by game young ensemble singers who did their best but could not compare with trained baroque dancers. But the small consort led by Goren performed on a comparable level with international ensembles like Les Arts Florissants, who have put this repertory on the musical map (festival director Wachner probably assisted in finding the best local baroque musicians).

Daniel Curran’s soft cultivated tenor brought out the pathos in Orphée’s pleas to Pluton. Mary Feminear’s dark complex soprano brought urgency to Proserpine’s intervention on Orphée’s behalf. The sweet tenor of Cullen Gandy and John Brancy’s vibrant baritone as Apollon emerged strikingly from the ensemble. In the final tableau, as Orphée led his Eurydice up the staircase into the light, one felt that this production augured a more fortunate operatic new year in 2014.

The Metropolitan Opera fielded striking new casts in several revivals in late 2013, including “Eugene Onegin.” The clunky Deborah Warner “Onegin” benefited from the return of Fiona Shaw polishing her direction with a new cast of riveting, if less vocally reliable, singing actors. Newcomers Peter Mattei, Marina Poplavskaya, and Rolando Villazón are singing actors who submerge themselves into their parts like method actors, while Anna Netrebko, Mariusz Kwiecien, and Piotr Beczala fit their glamorous personas onto the roles like old movie stars.

Mattei’s capacious baritone and towering presence made a more vocally imposing, convincingly authoritative Onegin than the boyishly affable Kwiecien. Poplavskaya was a riveting mess as Tatiana. Much more fragile and neurasthenic than Netrebko, Poplavskaya would start like a frightened animal when touched and suffered panic attacks fleeing Onegin’s company during their first encounter. The Pushkin/ Tchaikovsky heroine is supposed to be shy but not pathologically so –– one began to sympathize with Onegin’s initial reluctance to encourage any intimacy with this unstable young girl. Poplavskaya’s mournful cool timbre suits the character but she was constantly adjusting her placement, finding the parts of her voice that still work. All this musical control and intelligence should be directed toward reworking and rebuilding her technique from the bottom up so as to avoid incidents like her removal from Covent Garden’s new production of “Les Vêpres Siciliennes” just prior to her Met engagement.

Poplavskaya might avoid the fate of the dramatically gifted but vocally spent Rolando Villazón, returning after an absence as Lensky. Villazón’s current voice is like a pencil sketch of what was once a vibrant vocal canvas –– the colors and depth are gone but the outlines are still there. A gently floated phrase at the beginning of the Act II ensemble showed a flicker of what was and might have been –– he remains a fervently committed performer.

Stefan Kocán was another incongruously youthful, hunky Prince Gremin but sang quite well –– he is vocally improved this season. Elena Maximova’s rosily pretty blonde Olga became more tonally focused after a foggy sounding opening aria.

Conductor Alexander Vedernikov (not the 20th century bass, his father) was not profound but brought a more convincing romantic sweep to the score and kept the singers with him, unlike Valery Gergiev, his Putin-supporting predecessor.

Michael Mayer returned to the Met to restage his Vegas “Rigoletto” with several interesting singers making company and role debuts. Formerly a glamorous matinee idol in any role, Dmitri Hvorostovsky transformed himself via age makeup, padded waist, stooping posture and a balding gray wig into an ugly, leering, cynical Rigoletto. Robbed of his good looks, Hvorostovsky revealed himself as a vital, energetic singing actor. Unfortunately, this and other dramatic Verdi roles have removed some of his vocal glamour. Hvorostovsky has a secure ringing top but the middle voice velvet was replaced by gruff declamation, and tender lyrical sections like “Ah veglia o Donna” or “Piangi fanciulla” shortchanged legato and elegance.

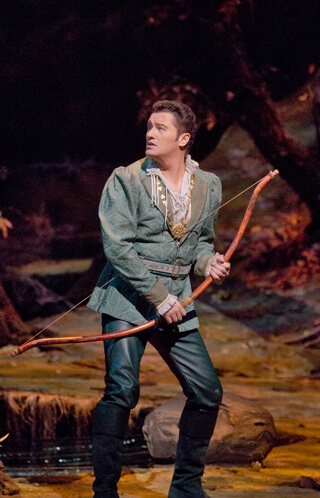

Matthew Polenzani was more an affably amoral Perry Como than a brash Sinatra as the Duke. Polenzani’s elegant phrasing and scrupulous musicianship brought out the bel canto refinement in Verdi’s music, making him a subtly disarming seducer.

Two debutant Slavic sopranos replaced the pregnant Aleksandra Kurzak –– the Russian Irina Lungu followed by the rising Bulgarian Sonya Yoncheva. The slender engaging Lungu has a vibrant, ruby-toned coloratura that accurately shaped the notes like a classical violinist. The raven-haired alluring Yoncheva, currently Europe’s operatic “it” girl, revealed full lyric voice with a high extension. Her voice’s dark core has a silvery overtone enlivened by a quick spinning vibrato. It’s just at the point where it needs to move beyond light coloratura roles into Violetta and Mimi –– the notes are there but not effortlessly.

The wonderfully reptilian Stefan Kocán reveled in Sparafucile’s low F, while Oksana Volkova still sounded blowsy as Maddalena. Youthful conducting sensation Pablo Heras-Casado brought vital forward moving tempos to Verdi’s score without sacrificing detail or depth. He seems a fine acquisition to the Met’s roster.

Mayer’s directorial gimmicks still get inappropriate laughs yet the audience and cast seemed engaged with the work and each other –– unlike the previous production, which was being walked through listlessly in later revivals.