Continuing litigation efforts that date back a quarter of a century, a group of “gentlemen’s cabarets” — which the court alternatively describes as “strip clubs” — and adult bookstores located in Manhattan have brought suit to challenge the constitutionality of the 2001 Amendments to the city’s Zoning Resolution as they apply to “adult establishments.”

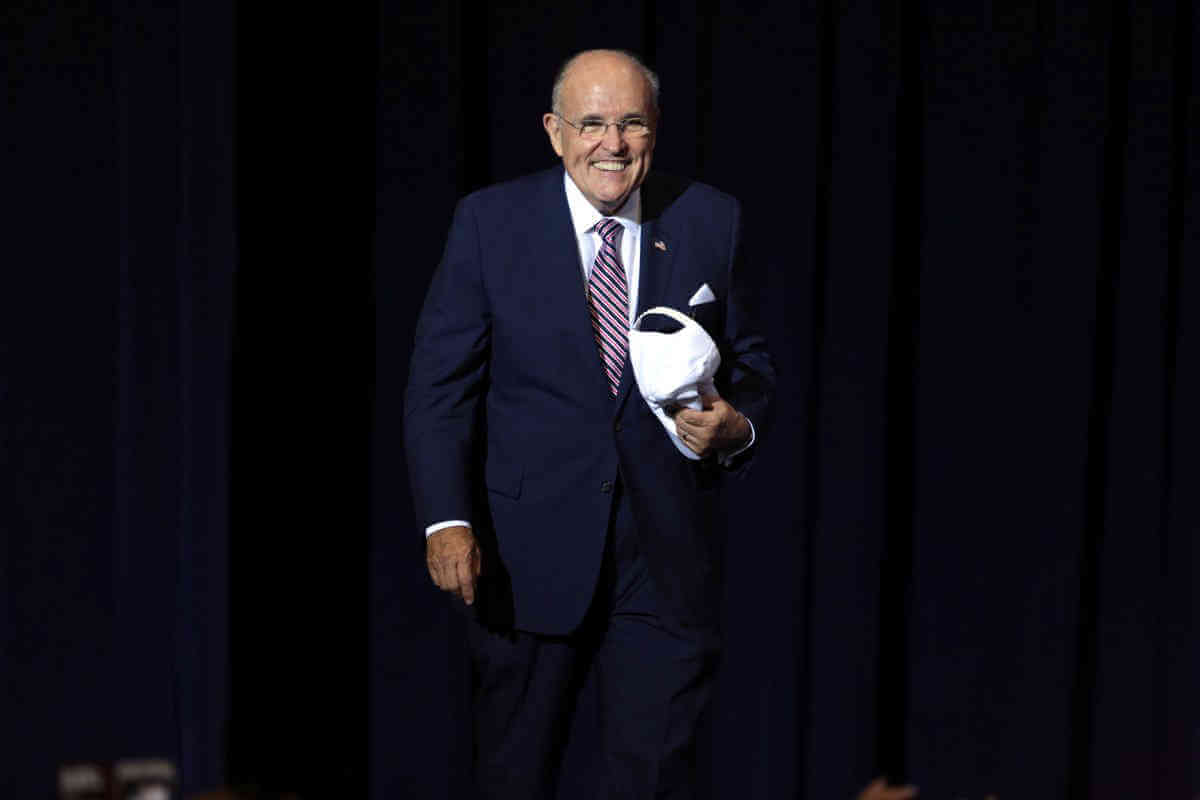

Numerous prior assaults on the zoning measure, adopted during the mayoralty of Rudy Giuliani in an attempt to sharply reduce the number of adult establishments and relocate them away from residential districts or close proximity to religious institutions, schools, and other places where minors tend to congregate, were largely unsuccessful once they proceeded to the appellate level.

Surprisingly, however, given the city’s earnest attempts to beat back all these challenges, US District Judge William H. Pauley III, in a September 30 ruling, noted that the city has not actively enforced the zoning regulations for the 18 years since Giuliani left office. Mayors Michael Bloomberg and Bill de Blasio turned their attentions elsewhere.

But the plaintiffs are concerned with the measure still on the books and the possibility it might be enforced against them in the future. That concern motivated this latest lawsuit.

In this ruling, Pauley granted the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction against the measure’s enforcement while the litigation goes forward on the merits.

The list of counsel accompanying the opinion goes on for two pages, and the judge mentions that in connection with the pending motions, “the parties have offered a Homeric record of affidavits, documentary evidence, and stipulations.”

Most significant among the objections to zoning regulations, perhaps, is that they were premised on a 1995 study of “secondary effects” attributable to the presence of adult establishments, especially when several were located close together. The reality, however, is that given enforcement efforts during the early years of the Giuliani administration as well as the residential and commercial development activity in the city over the past 20 years, the 1995 study is clearly out of date and no longer easily supports the Council’s conclusion that the rather drastic restrictions on the siting of adult establishments are still necessary in terms of public order and their impact on property values. Enforcement under Giuliani reduced the number of adult establishments and led to many of those remaining to significantly modify their activities to avoid being labeled as adult establishments.

“Tracing its origins to the City’s early 1990s crusade against adult entertainment businesses, this litigation has been ensnared in a time warp for a quarter century,” Judge Pauley wrote. “During that interval, related challenges to the City’s Zoning Resolution have sojourned through various levels of the state and federal courts.”

Pauley devoted significant space to reciting the history of that litigation, from the initial 1995 enactment through the consequential 2001 amendments and a series of judicial decisions that culminated in a 2017 ruling by the New York Court of Appeals that the most recent version of the measure is constitutional. The state’s high court ruling was stayed until the US Supreme Court denied review early last year.

This new lawsuit was brought by Manhattan businesses that were not considered “adult establishments” under the 1995 Regulation (which was construed by the courts to exempt establishments that devoted less than 40 percent of their space or stock to adult uses) but would be considered “adult establishments” under the 2001 amendments (which broadened coverage to deal with alleged “sham” reconfigurations that the city claimed many real adult establishments employed to evade the restrictions of the regulations).

The plaintiffs alleged that their First and 14th Amendment rights were infringed on, arguing that if the 2001 Amendment were actively enforced, they “would decimate — and have already dramatically reduced — adult-oriented expression.”

Pointing specifically to statistics from Manhattan, the plaintiffs argued that the 57 adult food and drinking establishments that existed in 2001 have been “culled to as few as 20” and of the roughly 40 forty adult bookstores with booths only 20 to 25 are still in operation. Of those bookstores, virtually none is located in “permissible areas” as defined by the zoning regulations. If the regulations were enforced, the plaintiffs maintained, there would be very few places in the city, much less Manhattan, where such businesses could operate — they would be restricted to “undeveloped areas unsuitable for retail commercial enterprises, such as areas designated for amusement parks or heavy industry or areas containing toxic waste.”

The plaintiffs also noted that the study of “secondary effects” conducted by the city prior to enactment of the 1995 measure has never been reexamined, never been validated in light of the rule restricting adult uses to 40 percent of an establishment’s space or stock, and was based on a cityscape radically different from what exists today.

In deciding whether to grant a preliminary injunction — and noting that the city is not actively enforcing these regulations — the court addressed several crucial factors: whether enforcement would inflict an irreparable injury on the plaintiffs, the likelihood the plaintiffs would succeed in their constitutional arguments, the balance of hardship between the plaintiffs and the city, and the public interest.

Assuming that the regulations, “which purportedly impose a direct limitation on speech,” violate the Constitution, Pauley concluded that the plaintiffs “demonstrated irreparable harm.” Here, Pauley pointed to many court opinions finding that monetary damages are insufficient to compensate somebody for a loss of their constitutional rights.

Turning to the plaintiffs’ likelihood of success on the merits, the judge found that the weak link in the city’s legal posture was the way in which the regulations, if enforced, would reduce the number of locations where adult establishments could operate. Court precedents require that regulation of adult uses must, because of its impact on freedom of speech, leave “reasonable alternative channels” for the speech to take place. In other words, the zoning rules must allow enough appropriate locations so that adult businesses can operate and members of the public can access their goods and services.

At this preliminary stage in the litigation, Pauley said he was “skeptical” the regulations would allow for “sufficient alternative avenues of communication.” The current map produced by the city Department of Consumer Protection indicates that there would be even less space allowed for adult entertainment under the regulations than were contemplated in 1995 — and that does not even take account of the requirement that adult establishments be no closer than 500 feet from sensitive locations or from any other adult establishment.

Finally, Pauley concluded that balance of hardships weighed in favor of the plaintiffs and that a preliminary injunction “would not disserve the public interest.”

Pauley’s concluding remarks leave little doubt about his view of whether there continues to be a need for the zoning regulations as amended in 2001.

“The adult-use regulations that are the subject of these now-revived constitutional challenges are a throwback to a bygone era,” he wrote, noting the city’s landscape has “transformed dramatically” since the “secondary effects” were studied 25 years ago.

Pauley set a status conference on the case for October 31.

The city would be advised to negotiate a settlement that would involve substantial revisions to the adult-use zoning provisions to reflect New York City’s changed circumstances. That could finally put to rest a long-running debate about this city’s commitment to allow for adult expression in public settings.