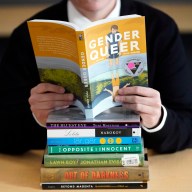

Nayyef Hrebid and Btoo Allami, the subjects of “Out of Iraq.” | MICHAEL LUONGO

MICHAEL LUONGO | It was an event mixing glamour, tragedy, and power — that last word literally. Samantha Power, the United States ambassador to the United Nations, was keynote speaker at a UN event focused on Iraqi LGBT issues, held amidst the ongoing refugee crisis caused by ISIS terror.

Glamour came in the person of moderator Omar Sharif, Jr., grandson of the famous Egyptian actor, who introduced a panel of experts on LGBT refugee issues along with the producers and stars of the documentary “Out of Iraq,” which had its New York premiere that evening.

The film, produced by World of Wonder and airing on Logo, the LGBT cable channel, tells the story of a gay Iraqi couple whose love for each other spanned 13 years and three continents before they were safely reunited in Seattle. Btoo Allami was an Iraqi soldier who met Nayyef Hrebid, a translator for Americans working with the Iraqi Army, in 2003, soon after the American invasion of the country.

US ambassador keynotes premiere of documentary chronicling love torn asunder

The two Iraqis were on the panel, along with Chris McKim who co-directed the film with Oscar-winner Eva Orner. Other panelists included Michael Failla, a Seattle entrepreneur who helped unite the Iraqi couple, Christine Matthews, deputy director of the UNHCR, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and Sean Eldridge, a 2014 upstate Democratic congressional candidate who is a board member at OutRight International, which has aided LGBT Iraqi refugees.

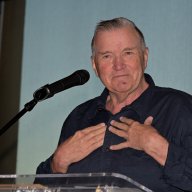

Samantha Power, the US ambassador to the United Nation, keynoting the New York premiere of “Out of Iraq.” | MICHAEL LUONGO

The documentary follows the couple from the beginning of their relationship in Ramadi, Iraq, which Nayyef describes in the film as “the most dangerous area in the world.” Despite the perils around them, from war and from the risk they would be found out by others in both the Iraqi and US armies, the two fell in love and now describe romantic nights within military encampments when they managed to steal away from others.

In her introduction to the film and panel, Ambassador Power said, “Nayyef and Btoo’s story is as important and illustrative as it is inspiring. It captures in the most human terms the existential threat that LGBTI persons face in many, many countries around the world. And it demonstrates why LGBTI rights and the plight of refugees are among the most pressing human rights issues of our time. In the process, this film and these individuals demand us to act to find some way, something in our own power to help.”

Sharif, who has spoken out on LGBT issues in the Middle East, including on Egypt, told Gay City News he became more aware of the plight of Iraqi gays through the film, calling it “moving and at once terrifying at the same time.”

In 2009, Nayyef was able to escape Iraq on a SIV, or Special Immigrant Visa — available to those who worked for or on behalf of the US government in Iraq — having to leave Btoo and his biological family behind. He settled in Seattle.

Omar Sharif, Jr., and Michael Failla, a Seattle entrepreneur who helped Btoo Allami finally be reunited with lover Nayyef Hrebid. | MICHAEL LUONGO

What they hoped would be a short separation stretches into years. It is here that the movie intensifies, showing the Skype videos and other ways in which the two continued their relationship over the Internet and through phone calls. Btoo eventually escapes to Lebanon, a relatively safe haven for persecuted LGBT Middle Easterners and a way station to refuge in the West. As Nayyef flourishes in his new home, Btoo begins to break down, his calls to Nayyef often fueled by alcoholic despair.

In the selfie-driven age of love among millennials, the film relies on an extraordinary amount of material provided by Btoo and Nayyef chronicling their relationship.

One of the film’s shortcomings is that it does not provide context on the American role in unleashing terror for LGBT Iraqis by invading and destabilizing the country. In fact, the film opens with images of Saddam Hussein and a discussion of laws under his rule against LGBT Iraqis. However, most LGBT Iraqis I interviewed for Gay City News during two visits to the country, in 2007 and 2009, said that gays were significantly safer under Saddam than under the American occupation.

Still, despite sidestepping the US role in giving space to the Iraqi and ISIS militias that persecute LGBTs and millions of others, “Out of Iraq” will help Americans understand what LGBT Iraqis must endure at home and what they encounter as refugees seeking safety under precarious conditions in other Middle Eastern countries.

The costs and difficulties of being a refugee are underscored by the nearly three years Btoo had to live in Beirut, illegally working to support himself and always under fear of deportation back to Iraq.

Btoo’s situation became particularly critical when a UNHCR worker botched an interview with him, accusing him of being a witness to torture at Abu Ghraib prison and therefore a war criminal after misinterpreting his explanation that he learned of the sadistic sexual torture there on TV news. There was no recording of the interview to go back to in order to correct the UNHCR error.

After ISIS and the Mahdi Army — the militia run by Muqtada al-Sadr behind many of the killings of gay Iraqis — only the UNHCR comes out as badly in the film. Failla, the entrepreneur who intervened in the case and helped bring Btoo into the US, was critical of the UNHCR both throughout the documentary and in the panel discussion.

Nayyef Hrebid.JPG Michael Failla gives Btoo Allami a goodbye hug in Times Square, as Nayyef Hrebid looks on. | MICHAEL LUONGO

Failla, who has a decades-long history of helping war refugees, starting with Cambodians, told Gay City News that the film is “here to educate people about LGBT persecution and murder and what is going on with people in different countries, and hopefully it will reach as many people as possible.” To the UN delegates in attendance, he said, “Please help support the LGBT communities in your countries so they are not killed and discriminated against. UNHCR, please help. Speed up the process and digitally record the interviews so there is no misunderstanding.”

The UNHCR’s Matthews explained that the documentary has already caused her organization to change the way it handles LGBT and other refugees.

“We need to do better for refugees, all refugees, including LGBT refugees,” she said.

Having said that, Matthews emphasized the overall refugee context, explaining that 22 million refugees need assistance from UNHCR, with 10 percent of those considered in acute risk, including LGBT refugees. Yet fewer than one percent of all refugees — about 100,000 — can be settled into third country safe havens every year.

Nayyef said he never expected his life to be made into a movie and shown at the United Nations.

“Ours is just a small story, one story, but we hope it will lead to change in the Middle East,” he told Gay City News.

Nayyef said he hopes audiences who see the film remember that for gay Iraqis, “it is not just ISIS or militias against them, it is the government, their own families because they are ashamed of them. They are the old generation. Our voice is for the new generation to see this change.”

Having helped bring over other Iraqi LGBT refugees, Nayyef said he believes few Americans understand the struggles those from his country continue to have even once they are in the US and other Western countries. He said he hoped Americans wishing to sponsor refugees understand “it’s not just that it should be money. The help could be for those LGBTs from the Middle East coming here because they are in shock. It is a new culture here. A new language. A lot of them do not speak the language. So put them in school, finish their paperwork. Just find them a job. Just help them with everything you could, because it is a big shock to them, culture shock. That is the problem I find for a lot of who come here. So we need to help them to stand up on their feet, so they could continue living here.”

To learn more about “Out of Iraq” and view a trailer, visit logotv.com/video-clips/0zm76j/logo-documentary-films–out-of-iraq.