I always felt different as a child. It was not until adulthood that I realized why: I am gay and disabled. I talk often about being an LGBTQ person, but rarely will you hear me talk openly about my learning disability. I sat through many years of psychoeducational testing in New York City public schools for what school psychologists and social workers believe is a learning disability.

To compound feeling dumb in school, I felt disinclined to fulfill the male gender stereotype despite constant bullying and harassment. I tried and tried to find people who could relate to me, only to be disappointed and alienated by others. Thank goodness, I never gave up! This journey has led me to the study and practice of an intersectionality approach with a focus on LGBTQ and disability identities.

You are probably wondering: Why should the LGBTQ population care? Because you could be one of the people I’m talking about or might become one of them in older age.

I first learned about the theory of intersectionality in doctoral studies in social work. I was relieved to finally find a theory that could explain things that I had experienced first-hand in both school and work. For the longest time, I thought it seemed like common sense that children who are both LGBTQ and disabled will experience greater oppression and discrimination than their non-disabled and/ or non-LGBTQ peers. Many studies that I came across in graduate social work education explored each identity separately. To me, it seemed silly to isolate parts of a person’s lived experience for analysis.

INTERSECTIONAL UNITY

The overarching principles of intersectionality involve the understanding of the interaction among multiple minority oppressions and of the social structures that continue to perpetuate hegemonic cultures and preclude social justice. Kimberlé Crewshaw, a law professor at both Columbia Law School and UCLA Law School, is the pioneer who coined intersectionality theory. She emphasized that our judicial system deals with identities discretely rather than looking at the whole person. This is becoming a bigger problem in the United States given how diverse we are and the many identities each of us possesses.

In the last five years, a public discourse has arisen on what it means to be multiply-stigmatized due to multiple minority identities. The information has been slow to percolate, but now research is beginning to make its way into the conversation. Recently, a study was published by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) on “Educational Exclusion,” which found the following results: more LGBTQ students with disabilities than non-disabled LGBTQ students are likely to drop out of secondary school, be disciplined, graduate at lower rates, and be involved in the criminal justice system. Additionally, when more than two marginalizations exist, the risks and challenges are elevated even further, potentially leading to a poorer quality of life. It seems obvious that this would be the case, but unless research is conducted and brought to Congress and policy makers, laws and practices remained unchanged.

For LGBTQ disabled individuals, there are few legal protections that exist either in school or at work. In schools, bullying is not covered under federal law, which leaves students who do not conform to norms at the whim of their peers and, sometimes, their teachers as well. Stopbullying.gov, a federal government website managed by the Department of Health and Human Services, notes that the following laws may help to protect minority and marginalized populations in school: Title IV and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Titles II and III of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

GLSEN, meanwhile, is actively pushing for the passage of the Student Nondiscrimination Act, which would prohibit discrimination in schools on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity and expression, just as bias is already banned based on race, religion, and disability. Additionally, the Safe School Improvement Act would require states to adopt anti-bullying policies that prohibit harassment on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity and expression and ensure that schools have appropriate mechanisms for dealing with such harassment.

School bullying continues to go unreported, leaving no recourse for the victim. And most communities have not made it their priority to support the passage of laws that protect vulnerable children. Those children are abandoned, left to their own devices. If they are fortunate, they don’t end up scarred or dead, from others’ violence or their own self-inflicted harm.

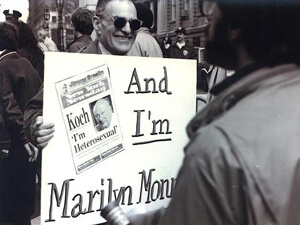

Gay City News has reported over and over again on states where an LGBTQ person can be fired based on their sexual orientation and/ or gender identity. No federal law protects LGBTQ employees; consequently, they must often hide or pass as heterosexual as best they can, which can have devastating effects on the their ego.

Now, let’s add another layer, in which you are both LGBTQ and disabled —and your disability is visible. What are your chances for being offered a position and keeping it? Organizational cultures are often resistant to employees about which stereotypes raise unfair inferences about competency, ability, and productivity. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, as amended in 2008, helps to protect this category of workers, and federal, state, and local equal employment laws and regulations have been utilized effectively as well. Far too infrequently, however, have these protections been extended to ensure full coverage for LGBTQ people with disabilities.

This is a call to action on the part of the LGBTQ population to understand we are diverse in our identities but all fighting for the same agenda: full civil rights and regulations that allow us to have access and opportunity in all areas of life without the fear of ridicule, abuse, violence, torture, neglect, oppression, and discrimination. Our first step is to evaluate what part we are playing in our own personal circles to change attitudes and combat ignorance through education and advocacy. And sometimes it is as simple as doing a Google search to find the information, joining listservs and groups, and making friends who can help shape the future.