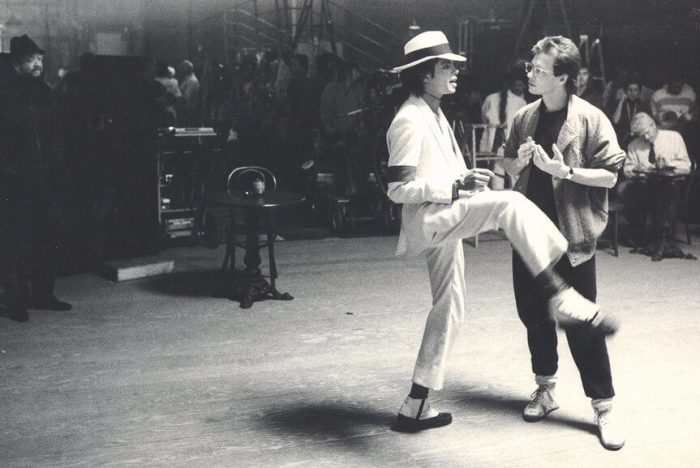

Julia Lima and Mikhail Svetlov in New Opera NYC's production of “The Golden Cockerel.” | STEVEN PISANO

BY ELI JACOBSON | Russian opera, like Russian literature, began at ground level with seminal author Alexander Pushkin. The first truly Russian opera, Glinka’s “Ruslan and Lyudmila,” is based on a Pushkin poem. Mussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov” is based on a play by Pushkin. Two Pushkin-derived operas by Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov were performed in New York in April and May – one familiar, the other a rarity.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s “The Golden Cockerel” (1907) was his last operatic composition. He used Pushkin’s absurdist fairy tale to satirize Czar Nikolai II’s aristocratic autocracy, imperialism, and in particular the Russo-Japanese War, which was unpopular with the Russian people and proved to be a military disaster for the empire. Rimsky-Korsakov also satirizes grand opera – such as “Ruslan and Lyudmila!”

In the opera, the foolish old King Dodon does not listen to his generals and launches a pre-emptive war against the neighboring kingdom. The Astrologer gives King Dodon the gift of a magical Golden Cockerel, which will sound forth prophetic warnings of danger. The chaos and ineptitude of Dodon’s campaign incites needless bloodshed causing the death of both of his sons. The King then succumbs to lustful pleasures – specifically with the alluring Queen of Shemakha, whom he takes as his new wife. When the Astrologer demands the Queen for himself in payment for the Cockerel, Dodon refuses and attacks the Astrologer. The Cockerel responds by pecking Dodon to death. The Queen and the Cockerel then disappear into thin air. In an epilogue, the Astrologer tells the audience that none of the characters in the opera were real with the exception of himself and the Queen of Shemakha. (King Dodon reminds me of a certain much discussed world leader of the current day… but let’s not bring a Public Theater controversy down on the fledgling New Opera NYC that presented this opera.)

The Metropolitan Opera performed the opera in French as “Le Coq d’Or” for nine seasons beginning in 1918. In the last season the Met performed the opera – 1945 – it was sung in English translation. In the early 1970s, it was performed by the New York City Opera in English with Beverly Sills and Norman Treigle. Traveling Russian troupes, including the Maly Opera, have visited New York and performed the opera in Russian.

New Opera NYC presented four fully-staged performances of “The Golden Cockerel” in Russian with full orchestra from May 18 to 21 at the Sheen Center on Bleecker Street as part of the annual New York Opera Fest. The company was founded in 2012 as the brainchild of Igor Konyukhov, a nuclear physicist who after emigrating to the U.S. turned his attentions to choreography and directing opera. The company’s resident star is bass Mikhail Svetlov, a former soloist at the Bolshoi Opera, who performed King Dodon.

These mad Russians, through sheer guts, improvisation, and imagination, whipped up a wild spectacle that surprised and dazzled the eye and ear. All this was achieved on a shoestring budget. This wasn’t a slick production by any means but with this sort of renegade group one has to take the rough with the smooth. The set and props designed by Zachary M. Crane featured black velvet curtains spattered with psychedelic paint. (Konyukhov posted a Facebook selfie of himself on all fours dripping the paint on the drops.)

Olga Maslova’s eye-popping costumes featured patterned pajamas in day-glo colors with wild headpieces: Dodon sported an oversized gold motorcycle cap. The Queen of Shemakha looked like a cross between a Cirque de Soleil showgirl and Lady Gaga. The Queen’s costume consisted of a skirt composed of strips of LED lights, bare midriff and a brass bra, Valkyrie helmet over long golden braids, and glow-in-the-dark orange makeup. The Golden Cockerel sported a huge golden headdress constructed by “La Gioconda” that resembled a mash-up of Flash Gordon and King Tut.

Konyukhov’s direction was unafraid to go for broad, outrageous physical comedy with a fine appreciation for bad taste. Imagine Benny Hill doing Russian fairy tales and you’ll get the idea. The overall style aesthetic can be described as Brighton Beach Russian nightclub meets Diaghilev on LSD in a dark alley. It was all too much and shouldn’t have worked – but somehow it did.

Svetlov (who has also performed as Mikhail Krutikov) sang a small role in the Metropolitan Opera’s new production of “Boris Godunov” in 2011 and has covered larger roles there since then. He would have been very welcome on the Met stage as Prince Gremin in its “Eugene Onegin,” any of the bass roles in “Prince Igor,” and especially as King René in “Iolanta,” where the originally cast singer and his understudy/ replacement were both subpar. Svetlov is a true bass with an imposing tone and stage presence used here with wit and larger than life abandon.

Julia Lima as the seductive Queen of Shemakha worked that bizarre outfit like a runway model displaying impressively chiseled abs (she maintains a second career as a bikini and fitness model). But this winner of the Grand Prix in the 1999 Siberia Vocal Competition also possesses a soprano voice as voluptuous as her figure that filled out the vocal line as fully as she filled out her scanty costume. It is a larger voice than the light coloratura usually cast in the role. Outside of one pitchy high cadenza in the famous “Hymn to the Sun”, Lima sang confidently with round, gleaming tones.

The rest of the voices were young and promising. John Villemaire smoothly managed the tricky range of the Astrologer, moving from lyric tenor to character falsetto countertenor with ease. Soprano Ksenia Antonova as the Cockerel too often sounded more tinny than golden, while Ksenia Berestovskaya as Amelfa the Cook has a richly promising youthful contralto. Antonio Watts and Dmitry Gishpling-Chernov made attractive sounds while acting doltish as Dodon’s half-witted sons. The small chorus was game. Conductor J. David Jackson had a clear sense of Rimsky-Korsakov’s minor key orientalist harmonies and firmly led the pick-up orchestra despite a few passing rough spots of bad string intonation and patchy ensemble.

Everyone in the (largely Russian) audience had quite a good time including two Orthodox Russian priests! One eagerly anticipates what. Konyukhov and New Opera NYC will come up with next.

Peter Mattei in the Met's production of “Eugene Onegin.” | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Pushkin’s novel in verse “Eugene Onegin” satirizes the youthful pretensions of his protagonists while sympathizing with their foibles, failures, and heartbreak. Tchaikovsky’s opera pretty much jettisons the social satire and goes right for the passion and heartbreak as operas usually do.

In April, the Metropolitan Opera revived its 2013 production of “Onegin” as a vehicle to reunite Anna Netrebko and Dmitri Hvorostovsky as the star-crossed not quite lovers. Alas, Hvorostovsky’s treatments for brain tumors occasioned his withdrawal early last year from this revival and the HD transmission. In his place, Met was able to secure the services of Mariusz Kwiecien and Peter Mattei who have previously sung Onegin during the initial run of this production. (Mattei performed Onegin on the HD.)

Deborah Warner’s dowdy, visually monotonous production (recreated by Paula Williams) was a neutral factor here. The general energy of the cast was high, and they performed with emotional engagement even when the direction was misguided or just obtuse.

Netrebko was a Tatiana of almost overwhelming vocal splendor pouring out waves of rich lush tone. Despite looking rather overripe with a dark peach makeup job and full red lips, she acted the awkward, insecure teenaged Tatiana more convincingly this time around. I still don’t like her grown-up Princess Gremina – she is directed to play the final scene as a vengeful turnabout seduction and rejection complete with kiss-off finale and slow contemptuous exit. That is a Tatiana neither Pushkin nor Tchaikovsky would have known – we needed more regret and sacrifice there.

Kwiecien and Mattei had totally opposite interpretations of Eugene Onegin. Kwiecien’s Onegin was a self-absorbed narcissist seducer. Mattei was the “superfluous man” archetype of Russian literature – the well-meaning but ineffectual aristocratic intellectual and idealist prone to boredom, cynicism, and flouting social conventions. The “superfluous man” tries to be virtuous but he ends up drinking, gambling, dueling, and messing up his own life and those of his friends and lovers.

Mattei was the clear vocal champ here – Kwiecien sang himself out early on, often sounding hoarse at forte levels. In the final duet, Netrebko sang Kwiecien off the stage. Mattei didn’t go for power but smooth legato. He also nailed the optional final high F in Onegin’s Act I aria “Kogda bi zhizn,” holding the note and executing a suave diminuendo over the concluding bars.

Alexey Dolgov as Lensky displayed the typical “white” sound of Russian lyric tenors but acted the role superbly – this poet was a passionate nerd whose fragile ego couldn’t handle a perceived rejection. His phrasing was what made his farewell aria “Kuda, Kuda” memorable, not sheer beauty of tone. Elena Maximova’s blonde and boisterous Olga was stylistically apt though less than ideally firm of tone in the low alto range.

Seasoned veterans Elena Zaremba and Larissa Diadkova returned from the premiere cast to steal scenes and hearts as Madame Larina and Filippyevna. Stefan Kocán scored in his big aria as Prince Gremin while looking absurdly young and fit for a grizzled old military veteran – another dramatic choice that undercut Tatiana’s self-sacrifice. Robin Ticciati conducted an unashamedly romantic reading of the score that hung fire in the big Act II ensemble but otherwise cut right to the heart of the matter.