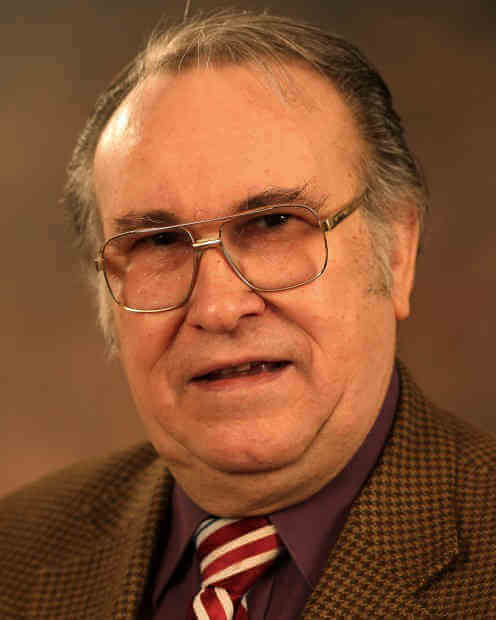

Kelvin J. Cochran, who was discharged as chief of the Atlanta Fire and Rescue Department (AFRD) after he self-published a book voicing negative views, based on his religious beliefs, about homosexuality and same-sex marriage, has struck back at the city and Mayor Kasim Reed with a lawsuit claiming a violation of his constitutional rights.

US District Judge Leigh Martin May, on December 16, dismissed some of Cochran’s claims, but allowed others to go forward.

Cochran became the Atlanta fire chief in 2008, left for 10 months in 2009 to serve as administrator of the US Fire Administration in Washington, but returned to the Atlanta post until he was suspended and then discharged on January 6 of last year.

Federal court must decide how free a major appointee is to stray, as a private citizen, from city’s policies

Cochran, self-described as a devout evangelical Christian and an active member of Atlanta’s Elizabeth Baptist Church, wrote “Who Told You That You Were Naked?: Overcoming the Stronghold of Condemnation,” which grew out of a men’s Bible study group at his church. Intending to provide a guide to men to help them “fulfill God’s purpose for their lives,” Cochran wrote that any sexual activity outside of a traditional heterosexual marriage should be avoided and specifically asserted that homosexual activity and same-sex marriage are immoral and inconsistent with God’s plan.

Cochran had consulted the city’s Ethics Officer about whether a public official could write a “non-work-related, faith-based book,” and was told he could do that “so long as the subject matter of the book was not the city government or fire department.” He did not, however, obtain a written ruling on that point. He later received the Ethics Officer’s approval for identifying himself in the book as Atlanta’s fire chief.

Cochran put the book up for sale on Amazon.com, and distributed free copies to individuals, including Mayor Reed, some members of the City Council, and various Fire Department employees whom he considered to be Christians (some of whom had requested copies).

A Fire Department employee who saw the book and objected to its statements about sexual morality contacted City Councilmember Alex Wan to complain, which led Wan to initiate discussions among “upper management” of the city. After those discussions were brought to the mayor, Cochran, on November 24, 2014, received a letter informing him he was suspended without pay for 30 days while the city determined what to do.

Among other things, the city cited an ordinance prohibiting city officials from engaging in outside employment for pay without written permission from the Ethics Office. At the same time, Reed went public in disagreeing with Cochran’s views, stating, “I profoundly disagree with and am deeply disturbed by the sentiments expressed in the paperback regarding the LGBT community.”

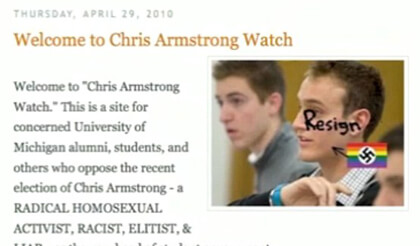

Councilmember Wan released a statement saying, “I respect each individual’s right to have their own thoughts, beliefs, and opinions, but when you’re a city employee, and those thoughts, beliefs, and opinions are different from the city’s, you have to check them at the door.”

After extensive media attention, Cochran was informed of his discharge in the first week of 2015.

Atlanta enacted local legislation banning sexual orientation discrimination many years ago, and has long provided benefits for same-sex partners of city employees. At the time this controversy arose late in 2014, a federal district court had ruled against the constitutionality of Georgia’s ban on same-sex marriage, but the matter was still pending on appeal in the courts. Atlanta government leaders had openly supported the marriage equality litigation, and Cochran’s views expressed in the book were out of synch with that perspective. In his federal complaint, however, Cochran claimed he was never accused of discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation as fire chief.

Cochran’s lawsuit poses a classic and recurring policy question: to what extent can a state or local government require public officials to refrain from publicizing their views on controversial public issues when those views conflict with official policies articulated by politically-accountable officials? The US Supreme Court has issued a series of important decisions since first addressing this issue in 1968 in Pickering v. Board of Education. That case involved a public high school teacher discharged after publishing a letter in a local newspaper critical of the local board of education’s budget proposals.

The high court, in Pickering, held that public employees are protected by First Amendment free speech rights when expressing views on matters of public concern when they are speaking in their capacity as private citizens. Such protection, however, is not absolute: the court must conduct a balancing test weighing the employee’s free speech rights against the employer’s legitimate concerns about being able to carry out governmental functions. Speech that results in disruption of those functions may lose its constitutional protection.

Subsequent rulings have clarified that when a public employee is speaking in an official capacity, he is speaking for the government and can be disciplined or discharged when his speech contradicts government policy.

Cochran filed a nine-count complaint against the city and Mayor Reed, raising various claims under the First and 14th Amendments. Dismissing some of those claims –– and finding that Reed enjoyed qualified immunity from personal liability –– Judge May concluded that his complaint alleged facts sufficient to maintain several of his First Amendment claims as well as one of his 14th Amendment Due Process claims.

Cochran’s complaint asserts he was fired in retaliation for constitutionally protected speech. May determined that Cochran’s speech satisfied the requirement that it be on a matter of public concern and that he was speaking as a private citizen (even though his book identifies him as the city’s fire chief), making his claim subject to the Supreme Court’s Pickering balancing test.

The city argued that the fire department has a “need to secure discipline, mutual respect, trust, and particular efficiency among the ranks due to its status as a quasi-military entity different from other public employers.” Consequently, Cochran’s “interest in publishing and distributing a book ‘containing moral judgment about certain groups of people that caused at least one AFRD member enough concern to complain to a City Councilmember,’” the city asserted, according to May’s opinion, does not outweigh the city’s interests in securing discipline and efficiency.

May noted that in considering a motion to dismiss, she must evaluate the complaint based solely on the plaintiff’s allegations, which in this case asserted that the book did not threaten the city’s ability to administer public services and was not likely to do so. Cochran claimed it would not interfere with the fire department’s internal operations and that he had never told any employee that complying with his teachings or even reading his book “was in any way relevant to their status or advancement” within the department.

Consequently, as a matter of law, May could not find at this stage in the case that the city’s interests outweigh Cochran’s free speech rights.

“However,” she wrote, “the factual development of this case may warrant a different conclusion.”

Cochran’s suit also alleges violation of his religious liberty rights, claiming he was terminated because he expressed his religiously-based viewpoint. The city’s response was that he failed to allege that his religion compelled him to publish his views while serving as fire chief without obtaining prior written approval or compelled him to distribute the book to city employees.

May ruled that Cochran need not have made such allegations in order to state a valid religious liberty claim, and she similarly found that Cochran adequately alleged facts to support another claim, that the city’s action violated his First Amendment right to freedom of association “by terminating him for expressing religious beliefs in association with his church.”

Turning to Cochran’s Equal Protection Claim under the 14th Amendment, May found that Cochran had failed to allege sufficient facts there. Most significantly, he had not identified somebody similarly situated who had articulated the opposite point of view without incurring adverse action from the city. Cochran had pointed to Mayor Reed, who publicly voiced opposition to his views, but the judge pointed out that Reed, as the elected chief executive of the city, was not similarly situated to Cochran, an appointed department head.

“As the Mayor,” May wrote, “Reed is Plaintiff’s superior… As the City’s ultimate decision-maker, Reed could not be similarly situated to Plaintiff, who is subject to Reed’s decision-making power.”

It appears that Cochran is the only appointed city department head who had published a work of this kind.

May also dismissed Cochran’s claim that the city’s policy about outside work by city officials cited in support of his discharge was unduly vague. And, she found that the public comments by Reed about the controversy were not sufficiently personally “stigmatizing” of Cochran to sustain a “liberty interest” claim under the Due Process Clause.

Cochran can, however, pursue the claim that because he has a “property interest” in his job he was deprived of it in the absence of fair procedures because his firing was unilaterally decided on by the mayor.

Ultimately, the question confronting May is whether the Atlanta city administration is required to keep in office an appointed department head who has published views that are out of synch with the city’s policies. If Cochran were a rank and file employee, he might well win some of his claims. But as a department head with supervisory authority over a major public safety agency, he will confront significant difficulty in arguing that the elected officials responsible to the voters are constitutionally required to keep him in office, as May intimated in emphasizing that her ruling on his first free speech claim may be reversed by “the factual development of this case.”