A Brooklyn organization that focuses on HIV prevention and sexual health among African-American gay and bisexual men will go on hiatus for the summer while it reorganizes from its current grant-based funding scheme to a fee-for-service provider model under which it will deliver mental health, substance abuse, and other services to its clients.

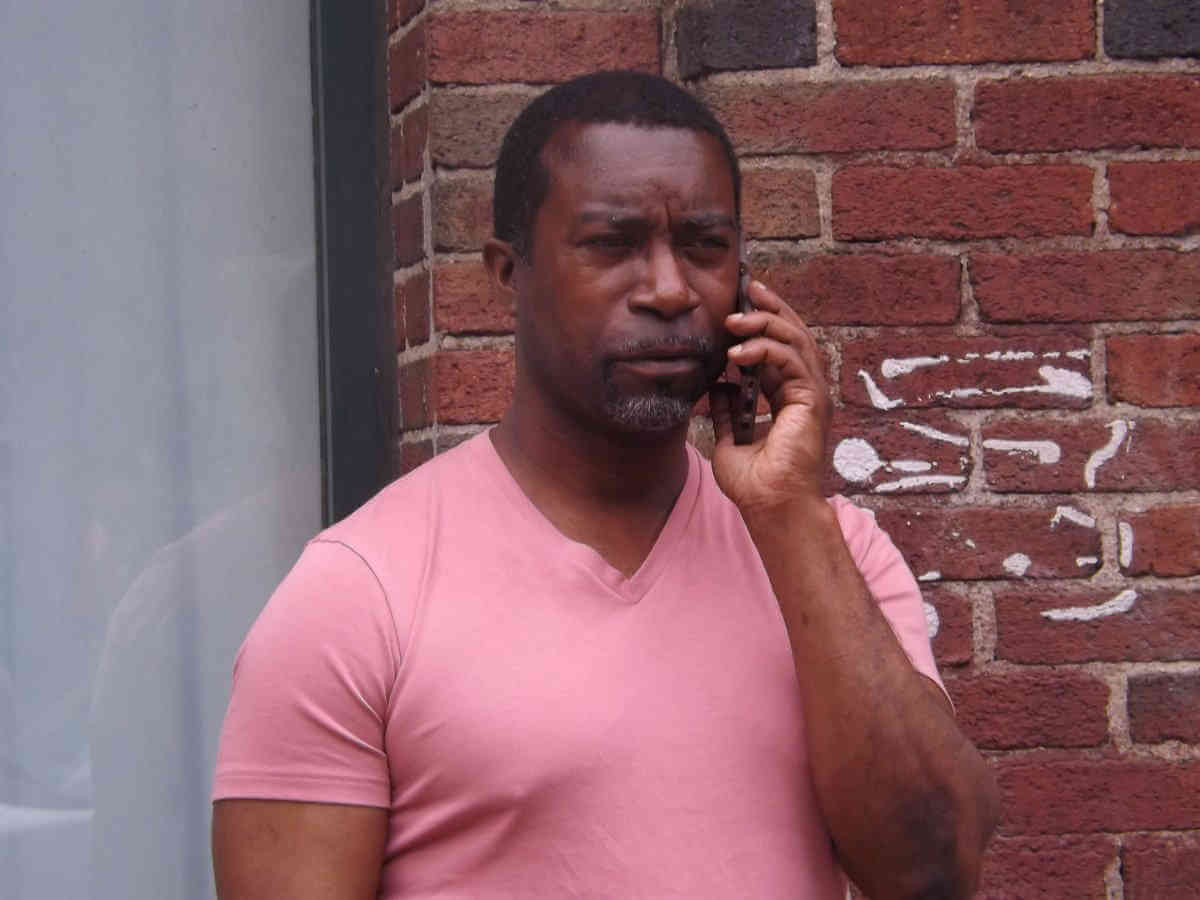

“We have discussed needing to shift,” said Vaughn Taylor-Akutagawa, the executive director at Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD). “Just being a grant recipient is not sustainable.” Founded in 1986, GMAD has not adapted to newer service models required by government funders that first emphasized expanded HIV testing. Given its smaller size, GMAD could not produce the volume of testing that government agencies wanted. More recently, funders required organizations to swiftly move people who tested positive for HIV into treatment so that the virus is suppressed to the point that they cannot infect others. Funders also seek to move people who are HIV-negative but at risk for the virus on to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which is a pill-a-day regimen that prevents HIV infection. These HIV prevention strategies require that funded agencies see large numbers of clients.

Over time, government grants became GMAD’s primary revenue source, but it could not produce the volume of results that government funders wanted and so that funding has steadily disappeared.

As an alternative, GMAD is seeking licenses from the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and from the state Office of Alcohol and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) to deliver mental health and substance abuse services at its Atlantic Avenue office. That will allow the agency to bill Medicaid and private insurance for services.

“The model we worked on just wasn’t working,” Taylor-Akutagawa said. “Our idea is to spend this time, since it’s quieter, getting ready for the Article 31.”

An Article 31 license allows a provider to deliver “integrated outpatient services” for clients needing mental health or substance abuse assistance.

CheckBook NYC, a site that is administered by the city comptroller’s office, indicates that GMAD received its last check from the city health department in October 2016. That was for $30,000. The agency received $50,400 in three payments from the state health department in 2018 with the last check being cut in April 2018, according to Open Book New York, a site that is administered by the state comptroller’s office.

Taylor-Akutagawa told Gay City News that GMAD just sent out its last voucher for a city health department contract this month, but that the contract had ended at the start of June. The agency laid off six people at the close of that contract and now has a staff of five.

Taylor-Akutagawa said that GMAD is four months behind on its rent. During an interview in GMAD’s offices, the agency’s chief financial officer said that the audit of the 2018 books was not yet complete so he could not say if GMAD has other outstanding debts. Gay City News found a single 2018 lien filed in Brooklyn court against GMAD by an alarm company, but Taylor-Akutagawa said that unpaid bill resulted from a dispute over the quality of the work. That lien was for just over $9,600.

GMAD has struggled with funding since 2010. Roughly 88 percent of its $1.3 million in revenue that year was from government sources. It lost an HIV testing contract with the city health department in 2011 because it was not testing enough people and other contracts were cut. Its revenue fell significantly over time. GMAD’s Form 990 for 2016, the latest year available, shows that its revenues went from $902,000 in 2012 to $419,000 in 2016. It ended 2016 with a $220,000 deficit.

While other agencies serve African-American gay and bisexual men, GMAD is the only agency with that singular focus though other activists, notably Gary English, who once headed People of Color in Crisis, have been trying to rebuild infrastructure to serve that demographic.

That capability is important because the Plan to End AIDS, which uses PrEP and treatment as prevention among other interventions, aims to reduce new HIV infections in New York to 750 annually by 2020. Since most of the new HIV infections in New York occur in New York City, the city has pledged to reduce new HIV infections in the five boroughs to 600 annually. While new HIV infections among many demographics, including white gay men, have been cut substantially, the rates among African-American and Latino gay and bisexual men remain stubbornly high. Neither the city nor the state will reach their goals if new HIV infections in those two groups are not reduced.

“I think the work we’ve done is amazing and dramatic,” said Taylor-Akutagawa who served on one of the committees that drafted the Plan to End AIDS. “There’s a lot more work to be done in black and brown communities to reduce the epidemic.”