Aaron Hamburger’s characters are Prague’s gays, Jews, and former Communists

One writer applies that notion to a Central European mecca for American expatriates in the last decade.

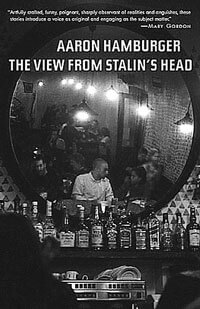

Aaron Hamburger gives us a carnival of the newly freed citizens of Prague in the 1990s in his delightful debut collection of stories, “The View from Stalin’s Head.”

Some Czechs, newly-liberated from Communism, do the macarena, while others convert to Judaism. Blind Czech priests go to U2 concerts. Meanwhile, gay American expatriates relish sleeping with go-go boys, or have affairs with their Israeli cousins, or marry women.

Despite the fact that Hamburger’s stories are populated by plenty of oddballs, his concentration on the good, old-fashioned business of creating characters ensures that it never becomes a grotesquerie.

In “This Ground You Are Standing On,” perhaps the best story in the collection, Sarah, an American descendant of Czech Jews, visits Prague with her husband, Carl, because they can’t afford Paris, London, or Rome. With a gentle hand, Hamburger sets up Sarah’s little house of cards: Carl is dying of cancer, and, having had one leg amputated, walks on crutches; Sarah’s mother, who has never fully accepted Carl’s conversion to Judaism, died a year before; at one point Sarah wishes she could say to her dead parents, “He was the best I could do.”

The ancient city offers sparks of adventure. Sarah and Carl let a renegade cab driver convince them to stay with an elderly widow, Mrs. Hubova, rather than in a hotel. Later, Sarah gets drunk with a group of meaty Czech men whom she finds “attractive in a course way,” while Carl naps.

At the heart of the story is the interaction between the proud and stately Mrs. Hubova and the distinctly suburban Sarah who wears a warm-up suit on her tour of the Terezin concentration camp. Sarah comes to suspect that Mrs. Hubova, who has lived in the same flat for 50 years, got the apartment during the Holocaust by reporting on the Jews who lived there.

When confronted, Mrs. Hubova retorts, “When you are guests in my home, you do not accuse me to be Nazi… Even when you are American.” Sarah’s indignation and new-found Jewish fervor are marvelously subtle expressions of her ambivalence at what life has been so far, and her terror at what it will become.

Hamburger, like Chekhov, knows that we are much more likely to weep at a character’s pain if we have already chuckled at her ridiculousness. Sarah’s story couldn’t be sadder if we witnessed her sobbing at her husband’s deathbed.

Hamburger does equally well when he ventures away from the world of tourists and expatriates to focus on native Czechs. In the collection’s title story, we meet a dissident artist who spent the Cold War drawing satirical pictures of Stalin. Having lived 16 years under government surveillance, he came to acclimate himself to it “like a prisoner loves his cell,” so much so that he now must pay a teenage boy to recreate surprise interrogations, barking orders, even strip searches. This wonderfully rendered story of pathology showcases Hamburger’s acute understanding of Central European psychology following the collapse of the Soviet Union, as well as his narrative artfulness. The teenager spins the old man’s history as he outfits his best friend with a suit and a pistol, enlisting him in the dangerous game.

Most of Hamburger’s stories, though, focus on the relationships between Americans and Czechs who never quite understand each other even when they’re speaking the same language. Hamburger is a master of the small, devastating moment, and the Czechs in his stories have the ability to slice through American hypocrisy with a simple phrase, the syntax of broken English notwithstanding.

“We are ready for your… enlightenment,” an old Czech man tells his teacher on the first day of English class. And Jirka, a tall, straight Czech man sleeps with a gay American and then says, “What do you think of our sex? I think is no so good idea.”

In these stories, as in life, freedom and adventure are often followed, with the force of a wicked hangover, by boredom and isolation.

“I drank and sniffed and sucked until my lips turned purple,” an American recalls in one story. “I got bored. And then a month later my mother came to visit me.”

Sound familiar?