The effort to overturn the ban on openly gay and lesbian US soldiers won a substantial New Year's boost when retired General John M. Shalikashvili said he would support an end to Don't Ask, Don't Tell.

By: PAUL SCHINDLER | The effort to overturn the ban on openly gay and lesbian soldiers serving in the U.S. military won a substantial New Year's boost on Tuesday when retired General John M. Shalikashvili, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the first four years of the Clinton presidency, wrote in a New York Times op-ed that he would support an end to the Don't Ask, Don't Tell policy in place since 1993.

“I now believe that if gay men and lesbians served openly in the United States military, they would not undermine the efficacy of the Armed Forces,” the former military chief wrote.

At the same time, Shalikashvili warned that “the timing of the change should be carefully considered,” and that it is best taken up only after the new Congress' “most urgent priorities, like developing a more effective strategy in Iraq” are tackled in order to “help heal the divisions that cleave our country.”

“Fighting early in this Congress to lift the ban on openly gay service members is not likely to add to that healing, and it risks alienating people whose support is needed to get this country on the right track,” he wrote.

In interviews with Gay City News, advocates-on Capitol Hill and elsewhere-for replacing the current policy with one that allows for open gay and lesbian service agreed that even with the retired general's support and new Democratic leadership in Congress, change will not come in the near term.

Though Shalikashvili did not originate the Don't Ask, Don't Tell policy-it was spurred by the resistance of his predecessor Colin Powell and the determined opposition of then-Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia, who headed the Armed Services Committee, to President Bill Clinton's plan to integrate the military-he was responsible for implementing it once its details were announced in December 1993 by Secretary of Defense Les Aspin.

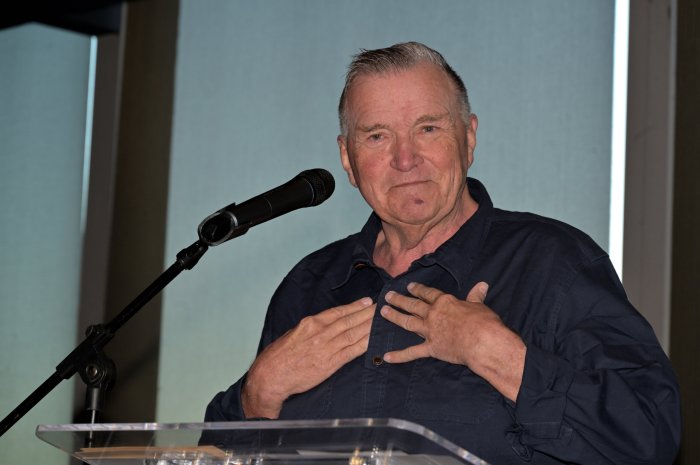

In the immediate wake of Shalikashvili's op-ed, William Cohen (also pictured on the cover), who served Clinton as defense secretary during his second term, became the first former Pentagon chief to voice the view that the policy is in need of review.

“It's time to start thinking about it and starting to discuss it,” Cohen told CNN's Wolf Blitzer late Tuesday. “I think what we're hearing from within the military is what we're hearing from within society, that we're becoming a much more open, tolerant society for diverse opinions and orientations.”

Cohen described the ban on openly gay and lesbian soldiers as “a policy of discrimination.”

Shalikashvili prefaced his argument this week by noting that President George W. Bush a week before Christmas called for an increase in the size of the U.S. military. A New York Times story about the president's statement cited an estimate from the Army chief of staff, General Peter J. Schoomaker, that his branch could only be grown by 6,000 to 7,000 soldiers each year. Discharges under Don't Ask, Don't Tell have been as high as 1,200 per year, though they have consistently been below 1,000 since 9/11. Still, the expulsion of highly trained personnel-including more than 300 gay and lesbian foreign language experts, at least 55 of whom had Arabic language proficiency-at a time of heightened homeland security concerns has created considerable consternation among authorities on military preparedness.

The former Joint Chiefs chairman explained that his new posture was influenced in part by his experience in speaking to gay and lesbian service members and veterans.

“Last year I held a number of meetings with gay soldiers and marines, including some with combat experience in Iraq, and an openly gay senior sailor who was serving effectively as a member of a nuclear submarine crew,” Shalikashvili wrote. “These conversations showed me just how much the military has changed, and that gays and lesbians can be accepted by their peers.”

He explained that back in the mid-'90s, in contrast, “I supported the current policy because I believed that implementing a change in the rules at that time would have been too burdensome for our troops and commanders. I still believe that to have been true.”

Shalikashvili took specific note of a Zogby poll completed last month for the Michael D. Palm Center at the University of California at Santa Barbara (formerly the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military) that found that of 545 military personnel who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, three quarters said they were comfortable interacting with gay people. He also pointed out that 24 nations, including Britain and Israel, allow openly gay service in their militaries. Last week, British defense authorities said they would step up advertising to potential gay recruits to address shortfalls in their force size.

According to Steve Ralls, a spokesman for the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network (SLDN), a Washington-based group that advocates on behalf of gay and lesbian military personnel and works to end the ban on their open service, his group in coalition with others helped identify gay and lesbian soldiers who could provide Shalikashvili with insight into their experiences. As for SLDN's knowledge that the former Joint Chiefs chairman was planning his written statement, Ralls said, “We knew that General Shalikashvili was considering doing the op-ed, but I was only informed that it was appearing by the New York Times the night before. We did know that he was working on the issue for some time.”

Ralls said the group had not anticipated the comments Cohen made on CNN.

Shalikashvili's change of heart and his statement regarding military effectiveness are significant. The argument that unit cohesion would be hurt by forcing heterosexual soldiers to serve in close, even intimate quarters with openly gay personnel was seized on by congressional opponents of Clinton's original goal of opening up the military-and federal courts since that time have consistently deferred to the Pentagon's judgment on that question.

And given that Clinton was forced by opponents to backtrack from his 1992 campaign pledge to the gay community in the face of a stormy backlash during his first days in office, it was politically vital to the president that he be able to maintain the fig leaf that the “compromise” would at the least curb the harassment that gay soldiers, in the closet or not, had long faced. The policy would purportedly protect any gay or lesbian soldiers who did not openly proclaim their sexual orientation, and when complaints arose early in its implementation that the purge of homosexuals in the military was actually increasing, it was often Shalikashvili's judgment that was publicly trotted out in defense.

For example, in March 1995, in the face of criticism of Don't Ask's implementation, Kenneth H. Bacon, a Pentagon spokesman, said, “Both [Defense] Secretary [William Perry] and General Shalikashvili have commented on the policy and say from their standpoint it seems to be working very well. It seems to be working very well from the standpoint of the commanders. That has been our experience, and it remains our experience.”

The same week, Mike McCurry, the White House spokesman, said, “The president is confident it's the right policy. He is concerned about some of the news reports that he's seen, anecdotally, providing information that some people have-the circumstances of which would seem to suggest there might be some problem implementing the policy. But he is-we have been in contact with the Pentagon on that and General Shalikashvili and Secretary Perry have both been very public and very detailed in explaining how the policy is working.”

This week's op-ed is not Shalikashvili's first foray into politics. In 2004, he appeared at the Democratic National Convention to endorse Senator John Kerry's presidential bid.

The new developments involving Shalikashvili and Cohen come after two years in which official Washington has edged closer to a formal re-evaluation of the Don't Ask, Don't Tell policy, the opposition of the current administration and many Capitol Hill Republicans notwithstanding. In March 2005, surrounded by four retired flag officers, Massachusetts Democratic Representative Martin Meehan introduced legislation to repeal the ban. He now boasts 121 co-sponsors, including incoming Speaker Nancy Pelosi-a tally just over half of the 218 needed to gain a House majority.

With California Republican Duncan Hunter at the helm of the Armed Services Committee in last year's Congress, no hearings were held, but the Boston Globe in a November article said that Meehan predicted hearings early in 2006 under the leadership of the new chairman, Democrat Ike Skelton of Missouri. Meehan, while noting that Skelton supports Don't Ask, Don't Tell, told the Globe that the new chairman was considering naming him to chair a subcommittee with oversight of the military policy. A spokesperson for Skelton told the Globe that no subcommittee assignments had been made as of mid-November.

In response to a request for comment this week, Meehan's office forwarded a more general written statement from the congressman, saying, in part, “Repealing Don't Ask, Don't Tell would be a landmark achievement for not just gay and lesbian rights, but for civil rights. The policy is detrimental to our national security and I'm glad to see that General Shalikashvili agrees… I am looking forward to continuing an honest dialogue with members of Congress and the general public, presenting all the facts, and making it clear that the policy is discriminatory, harmful to our military's readiness, and should be repealed.”

A call to Skelton's office was referred to Armed Services Committee staff, who did not return a phone request for comment. Nor did Hunter's office-nor those of the incoming and outgoing Senate Armed Services chairmen, Michigan Democrat Carl Levin and Virginia Republican John Warner-respond to requests for comment.

Ralls, at SLDN, voiced optimism that the debate is moving forward on Capitol Hill, even as he acknowledged that a central focus of efforts continues to be “education,” particularly of new Democratic representatives, many of them “conservatives, from very conservative districts.”

“Bringing them on board is not something that will happen overnight,” he said, explaining, “We're optimistic that next year at this time we will be much further along.” He added that Joe Sestak, a retired vice admiral just elected as the new Democratic representative from a suburban Philadelphia district, will be supporting a new policy on gay service.

Ralls also noted that, among congressional Republicans, retired marine Wayne Gilchrest of Maryland, who supported Don't Ask, Don't Tell in 1993, now favors its repeal. The SLDN spokesman said that a sponsor for Meehan's bill in the Senate, where it has not yet been introduced, will be announced soon.

Writing on TheGayMilitaryTimes.com, retired Coast Guard Rear Admiral Alan M. Steinman, who came out in late 2003 and was among those Shalikashvili met with during the past year, said, “I have long advocated that until the senior members of the military agree that gays and lesbians can serve openly, Congress and the White House would never agree to repeal the DADT law. No matter how strong the arguments we activists put forward, it would never be enough.”

Denny Meyer, editor of TheGayMilitaryTimes.com and president of American Veterans for Equal Rights New York (AVER-NY), was particularly upbeat about the Times op ed.

“What is significant here is that the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs at the Pentagon, at the time the Don't Ask Don't Tell law was enacted, has now said that gays should be allowed to serve openly,” he told Gay City News. “The process is reversed, the primary opposition to gays in the military at the time the law was enacted is now telling Congress that he is no longer opposed. A reason for reluctance in Congress is gone.”