Tsai Ming-liang’s visually arresting film is a tribute to his austere style

Only a middle-aged man could have made “Goodbye, Dragon Inn.” Most viewers under 35, who grew up watching movies on video, don’t share its nostalgia for the days when filmgoing involved an unpredictable interaction with other people, not just consumption.

“Goodbye, Dragon Inn” is set on a rainy night in Taipei, during the Fu-Ho movie theater’s final day of business and over the course of one screening of King Hu’s martial arts classic “Dragon Inn.” The screening draws a very small audience, who aren’t exactly hypnotized by the film. They get up to smoke, wander around, go to the bathroom and cruise.

For a New Yorker, “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” recalls pre-gentrification Times Square theaters, as well as the now-defunct Chinatown circuit. For a film that often seems to be about nothing, “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” packs a real wallop.

Here, Tsai Ming-Liang pares his austere style down to the bone––long takes and urban loneliness. There’s almost no dialogue or camera movement. Fortunately, Tsai has the eye of a painter and the ear of a musician. He’s sensitive to the variations of sound recorded off a movie screen and the percussive patter of rain outside the theater. “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” is stripped-down, yet richly sensual. Like the late French master Robert Bresson, Tsai is extremely attentive to the material world’s details. He often lets the camera linger for 15 or 20 seconds after a person has left the frame. There’s something beautiful to look at and interesting to listen to in every shot.

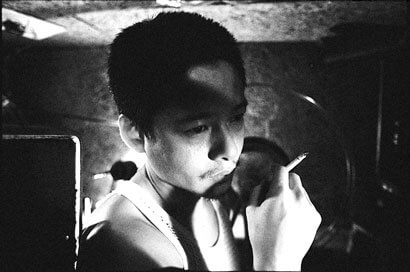

Tsai has been making film variations on the same theme throughout his career. That’s starting to change. In “Goodbye, Dragon Inn,” he uses his favorite actor, Lee Kang-sheng, once again, but Lee’s character is no longer part of a nuclear family. Tsai’s work might be unbearably bleak if it weren’t so funny, juxtaposing alienation and sexual frustration with slapstick and dry wit.

That sense of humor is mostly missing in “Goodbye, Dragon Inn,” although the film isn’t any more depressing for its absence. The playfulness that led him to make a sci-fi musical and end “What Time Is It There?” with a dead character’s resurrection is still present, but it’s subsumed into the general ambiance. Like Wong Kar-wai’s films, “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” is filled with a diffuse eroticism––Tsai brings out the beauty in everything in his camera’s path.

Some movies don’t necessarily gain anything from being seen on the big screen. The reflexive violence of David Cronenberg’s “Videodrome” or Michael Haneke’s “Funny Games” may hit home harder on the couch than in the theater, while Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Pulse,” in which ghosts launch themselves off the Internet in order to destroy the world, might benefit from being downloaded online and viewed on a computer monitor.

But the virtues of “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” would be obliterated on video. The small screen amplifies the relative importance of dialogue and acting––aspects of filmmaking which this film has little interest in pursuing––and reduces that of visual style. As Andy Warhol’s early films showed, celluloid can lend a monumentality to almost any subject. The flicker of light on a sign or woman’s face can be as much of an event as a tracking shot or shock cut. The beauty of “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” lies in taking apparent stasis and blowing it up larger than life.

Cinema isn’t dying, but the walls between film, video, TV, video games and the Internet are dissolving faster than most directors can keep pace with. In terms of focus, color reproduction and depth of field, video is still a limited medium, although it may look as good as 35mm film ten or 15 years from now. Without exactly being an anti-video manifesto, “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” documents the death throes of a certain kind of cinema. The heyday of films like “Dragon Inn” has passed, despite the recent surprise success of Zhang Yimou’s “Hero.” At best, they’re promoted from the realm of pop culture as artworks worthy of a museum setting; at worst, they’re simply ignored. However, “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” is as much about the movie theater––as a physical and social space––as about film itself. It’s a powerful elegy for a kind of filmgoing that no longer exists. Here’s hoping the rows of Cinema Village are more crowded than those of the Fu-Ho.