Pre-production gossip aside, “Taboo” deserves praise

Just before the lights went down for the second act of “Taboo,” Rosie O’Donnell, the producer, addressed the audience, a critic’s night, saying, “Thirty-one standing ovations. We must be doing something right. I want to say to all the critics here, we love you. To all those outside…” and she raised both arms above her head with middle fingers extended.

This brought a cheer from the audience, but it was unsettling for its vehemence. Certainly, O’Donnell’s frustration is understandable: our culture is swift to tear down projects that hearsay undermines. O’Donnell has every right to take those critics to task who have not invested the time or money in seeing what she has created. Her style may be abrasive and confrontational, but she reportedly paid for the whole show herself, and critics would not even be in their seats were it not for her passionate sponsorship of the production.

The problem, though, is that such an outburst upstages the very show we are there to see. It makes O’Donnell’s point of view more important than what is happening on stage, and that’s unfortunate, particularly during intermission. Rosie should relax. Despite its problems—and there are a few—“Taboo” is absolutely worth seeing.

Visually dynamic, thought-provoking, at times bold, the show is an amalgam of a typical, even sentimental, musical with a contemporary entertainment medium—the music video—a form that was just finding itself during the early 1980s, the period of the show.

The typical musical elements have echoes of “Follies,” in its melancholy reminiscence from the stage, of “Cabaret,” in the conceit of finding or losing oneself through a performance, and even of “Sweet Charity,” in its constant yet futile search for love.

Yet as familiar as these themes are, the effect of lumping them all together is to create a show that is often highly fragmented, even unfocused until one considers that these small bursts of emotion, at times seemingly unrelated, reflect the way a whole generation grew up learning to emote through music.

Those who came of age in the 1980s were weaned on music videos, rather than book musicals. Considered in this light, the artistic incoherence of the book becomes intriguing as it eschews linear storytelling and creates instead an impression of the world of Boy George and his cohorts that can feel as surreal as the world they invented and inhabited. It’s also fascinating to think about the story historically—the chaotic world Boy George and the club kids called “The New Romantics” was partially a response to the repressive, decidedly un-artistic England of Margaret Thatcher.

Where Charles Busch’s script seems weak is in the second act where the story switches from Boy George to designer/ performance artist Leigh Bowery. But when he’s at the top of his game, Busch exhibits a bitchy, biting wit juxtaposed with sentiment. Indeed, elements of the story are quite intimate, and the show might be more powerful in a smaller house. But “Taboo” is certainly far and away more engaging than the tedious “The Boy from Oz,” the other celebrity bio-musical on Broadway right now.

The story follows the haphazard, hardscrabble lives of a group of young people who have placed themselves on society’s fringes. Through provocative art, they engage in the power games inherent to their closed world of nightclubs and fashion design. The Leigh Bowery plot focus is all about the drive for fame and the struggle against AIDS, which robbed him of his chance at stardom. Everything changes when Boy George crosses over into the mainstream. Unintentionally, he shatters complacent expectations, and unfortunately “Taboo” then becomes a fairly stock showbiz drama—love won and lost, dueling divas, drugs, rehab, healing, huggy reunion, upbeat number, curtain.

Trite as this may seem, Boy George’s songs make the formula seem fresh. Whereas the Peter Allen songs in “The Boy From Oz” seem to have been pounded into the script with a mallet, Boy George’s numbers work much better in the book format—partly because of the episodic nature of the show, but largely because George’s songs are vastly better written. For all his external flamboyance, at the core, Boy George wrote substantive, intuitive music.

The company is extraordinary. As Boy George, Euan Morton is sensational. He looks uncannily like his alter ego, and his voice is clear and perfectly placed. He’s also quite a good actor and plays his character’s broad range convincingly.

George O’Dowd (a.k.a. Boy George) plays Leigh Bowery. He’s quite good as well, finding an understated performance that is a wonderful counterpoint to his outlandish costumes.

Raul Esparza plays Phillip Sallon, who is also one of the narrators. He does a fine job, being both in and out of the story as he’s required to be, and providing a comic through line. Jeffrey Carlson is stunning as the drag queen Marilyn, the one who, despite the help of Boy George, lacks the talent to be anything other than freakish. It is a harrowing and desperate portrayal and shows Mr. Carlson (last seen on Broadway as the son in “The Goat”) to be a performer of remarkable versatility.

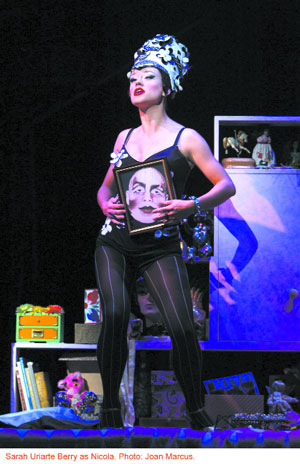

At first, Sarah Uriarte Berry plays Nicola, Leigh’s assistant and later wife, with a kind of barely controlled mania that is electric, before maturing into a more reasonable person when confronted with Leigh’s dying. Cary Shields plays Marcus, a composite character of all the men Boy George dated, with a lovely energy. Shields has a wonderful voice as well and his second act number “I See Through You,” is sad and chilling.

The direction by Christopher Renshaw makes the most of the show’s structure, and the design—scenery by Tim Goodchild, lighting by Natasha Katz, and costumes by Mike Nicholls and Bobby Pearce—is terrific.

Whatever you think of Ms. O’Donnell is not the issue. Broadway needs they believe in and to push the limits of theatre convention, especially with the musical form, as “Taboo” does. The challenge for “Taboo” is whether in the context of competitive Broadway and cold-hearted gossips, it can run long enough to find an audience. It deserves to.