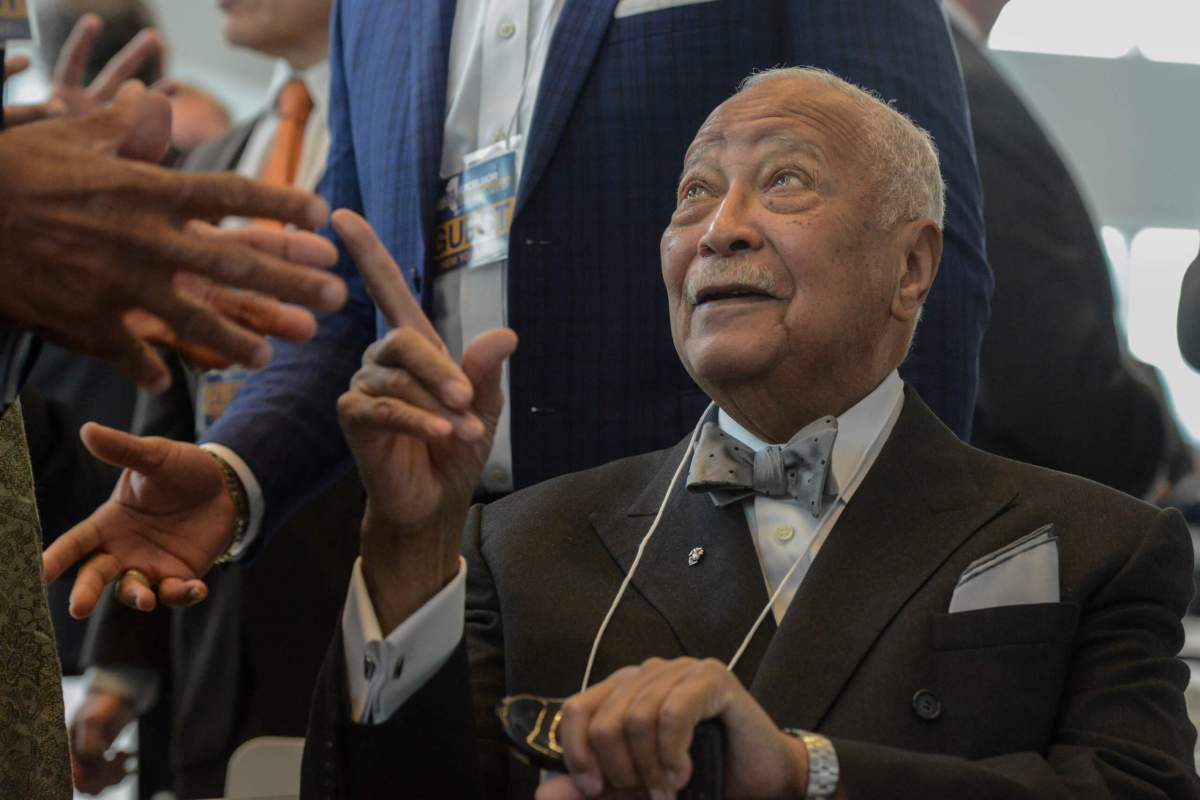

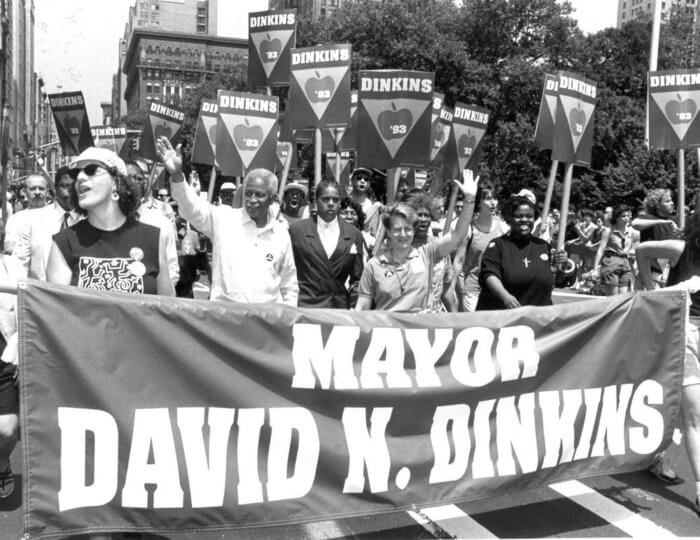

David Dinkins, who died at 93 on November 23, became mayor of New York in 1990 — a pro-gay Black man riding the desperate hopes of communities of color and LGBTQ people at a time of racial unrest in the depths of the AIDS pandemic.

As mayor, Dinkins advanced the rights of people in same-sex relationships, greatly enhanced AIDS services and education, and stood with the LGBTQ community in an epic conflict over the exclusion of the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization from the St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

All Dinkins ever seemed to want to be was Manhattan Borough president, an office the former city clerk and Harlem state assemblymember won in 1985 on his third try.

Standing with Irish gays, promoting AIDS education, recognizing same-sex couples key among his achievements

But in 1989, after 12 years of racial polarization under Mayor Ed Koch, progressives, LGBTQ people, people of color, and the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition of which he was a part turned to Dinkins — the highest-ranking Black official in the city —to challenge Koch in the Democratic primary. That campaign was managed by “the rumpled genius” Bill Lynch, who would become his deputy mayor.

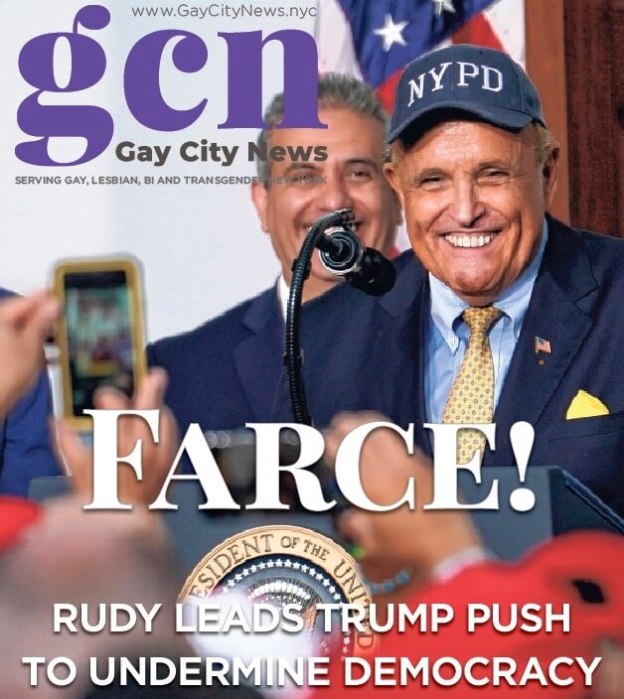

Many LGBTQ leaders and an AIDS movement radicalized by the emergence of ACT UP in 1987 worked hard to defeat Koch and elect Dinkins, the city’s first and, to date, only Black mayor. Dinkins bested Koch, Comptroller Jay Goldin, and civic leader Richard Ravitch in the primary, exceeding the 40 percent necessary to avoid a runoff. He then narrowly defeated federal prosecutor Rudy Giuliani, the candidate of white grievance.

At his inauguration on January 1, 1990, Dinkins reminded us that his ancestors were brought to this country “chained and whipped in the hold of a slave ship.” But, he added, “I see New York as a gorgeous mosaic of race and religious faith, of national origin and sexual orientation, of individuals whose families arrived yesterday and generations ago.”

When some of us were appalled after word emerged that he had invited Cardinal John O’Connor, New York’s virulently anti-gay archbishop, to give a prayer at the event, his team scrambled and enlisted the New York City Gay Men’s Chorus to sing from the balcony of City Hall.

ACT UP had hounded Koch in his last years as Mayor, fed up with his half measures on AIDS. But when Dinkins held a town meeting at the LGBT Community Center in February 1990, it turned raucous as he encountered a community already impatient with the pace of the changes needed. There was fury over Dinkins’ appointment — on the recommendation of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and AmfAR’s Dr. Mathilde Krim — of Dr. Woody Myers, a Black public health professional from Indiana, as health commissioner. In that same role for the State of Indiana, Myers had supported PWA student Ryan White in attending public school, but his nomination in New York was delayed when he told a reporter that quarantine was a possibility in the fight against AIDS. Myers lasted about a year.

Among appointments received more favorably were Dinkins’ posting of out gay Dennis deLeon as chair of the New York City Commission on Human Rights and out gay Dr. Billy Jones as mental health commissioner and later head of Health + Hospitals. I was among the 15 unpaid members of the Human Rights Commission. We weren’t the city’s first out commissioners — Mayor Abe Beame named Bob Livingston to the Human Rights Commission in 1976 and Koch had Henry Geldzahler at Cultural Affairs and David Rothenberg, Joyce Hunter, and Jim Levin at Human Rights — but Dinkins also employed an array of LGBTQ progressives in prominent positions, including Marjorie Hill as his liaison to the community, Allen Roskoff, also on the Human Rights Commission, and Barbara Turk as deputy director for Health and Human Services in the mayor’s Office of Management and Budget.

Dinkins had campaigned on a promise to extend domestic partner benefits to city employees, but said he felt constrained by the fiscal crisis that he inherited — the “money excuse” that did not sit well at all with a community that had no access to benefits while all heterosexuals did. He did establish the city’s first domestic partners registry in March 1993 — an important breakthrough that endures even with the advent of same-sex marriage — but waited until just a few days before his reelection bid to settle the six-year old lawsuit by gay and lesbian teachers seeking equal health benefits — a case brought by Ron Madson and Richard Dietz, Ruth Berman and Connie Kurtz, and a third, anonymous couple. The settlement extended benefits to all domestic partners of city employees — same-sex and different-sex. In the long run, more heterosexual couples took advantage of it.

The threat of HIV to young people came to the fore during his mayoralty. While few teenagers showed symptoms due to what can be a 10-year incubation period of the virus, many were getting infected. In 1991, the Board of Education’s AIDS Advisory Council — including Raymond Jacobs of the Young Adult Institute, Teri Lewis of the AIDS & Adolescents Network, and me from the Hetrick-Martin Institute, among others — put forth a comprehensive plan to the Board and Chancellor Joseph Fernandez for mandatory, explicit, age-appropriate AIDS lessons in all grades as well as free condom availability in high schools. It became an explosive battle in the culture wars, but Dinkins prevailed on his two appointees to the Board to join with those from the Bronx and Manhattan to enact the proposal by a 4-3 vote. Dinkins was willing to expend political capital to save lives.

Dinkins’ successor, Giuliani, ran on a platform of retrenchment on AIDS issues and when he took office banned condom lessons in classrooms.

There was a similar conflict over inclusion of LGBTQ issues in school curricula in the “Children of the Rainbow” controversy where, again, Dinkins stood with the community as others distorted it for political gain.

But Dinkins’ finest hour was standing with the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization (ILGO), a group of mostly Irish LGBTQ immigrants, in their bid to march in New York’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade on Fifth Avenue in 1991. At first ILGO was told no, there was a waiting list to get into the city’s oldest parade because the city put a limit on its duration. Dinkins offered to extend the march if that meant ILGO could participate but then the parade committee showed its true colors: they were not going to let a gay Irish group into what they were now calling a Catholic parade.

A compromise was reached in which the more liberal Manhattan Division 7 of the Ancient Order of Hibernians where Dinkins had allies would let ILGO march with them without their banner and Dinkins would march in solidarity with their contingent rather than at the mayor’s usual place of honor toward the front. The contingent was met with vitriolic hatred from the sidelines — many shouting “faggots” and “AIDS!” — and a beer can thrown at Dinkins barely missed him.

“Every time I heard them boo if anything it strengthened my resolve and convinced me this was the right thing to do,” he said at the time. “Most people in our town are good people.”

St Patrick’s Day Parade, NYC 1991-1992 from Lisa Guido on Vimeo.

Dinkins then wrote a stirring op-ed in The New York Times, “Keep Marching for Equality,” comparing his experience to what he went through marching for Civil Rights in the South in the early 1960s.

“It is strange,” the mayor wrote, “that what is now my most vivid experience of mob hatred came not in the South but in New York — and was directed against me, not because I was defending the rights of African Americans but of gay and lesbian Americans. Yet, the hostility I saw was not unfamiliar. It was the same anger that led a bus driver to tell me back in 1945, when I was en route to North Carolina in Marine uniform, that there was no place for me: ‘Two more white seats,’ he said. It was the same anger that I am sure Montgomery marchers and Birmingham demonstrators experienced when they fought for racial tolerance. It is the fury of people who want the right to deny another’s identity.”

When parade organizers outright banned Irish LGBTQ groups entirely, Dinkins honored ILGO’s boycott of the parade — a boycott broken by Giuliani, his successor Michael Bloomberg, and Senators Hillary Clinton and Chuck Schumer but renewed by Mayor Bill de Blasio, a former Dinkins staffer, who got the organizers to accept an Irish LGBT group, Lavender & Green, in 2016. (The complete, nuanced history of that controversy was written by ILGO’s Anne Maguire in her book “Rock the Sham: The Irish Lesbian & Gay Organization’s Battle to March in NYC’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade.”)

When Dinkins lost his re-election bid in 1993, he conceded the close race on election night, saying, “Mayors come and go but the life of the city must endure. Never forget that the city is about dignity, it’s about decency, it’s about the hope and determination of working people struggling to make a better life for their children and their children’s children. My friends, the gorgeous mosaic is alive.”

Most of Dinkins’ obits center on the racial strife that brought him to the mayoralty in 1989 and the racial discord that led to his narrow loss four years later. Giuliani exploited fear of crime for eight years as mayor — and gained a reputation for making the city safer while never acknowledging that it was the huge infusion of funding secured from Albany by Dinkins and Council Speaker Peter Vallone for the “Safe Streets, Safe City” program that vastly increased — for better or worse — the police force and started to bring crime rates down.

Dinkins would recall of election night in 1993, “Some in my group wanted me to demand a recount and so on. I said, no — in this country we don’t have coups and revolutions, we have elections.” That lesson was obviously lost on his successor at City Hall.

Dinkins’ beloved “bride” (as he said) of 67 years, Joyce B. Dinkins, died just this October. He is survived by survived by his children, David N Dinkins, Jr., and Donna Dinkins Hoggard, two grandchildren, and a sister, Joyce Belton.

I’ll always remember David Dinkins for his achievements on behalf of our community and as an exceedingly decent man and approachable leader who always sided with the oppressed, who spoke of our community’s rights not just at LGBTQ events but at presentations in Catholic churches as well, and who gave Nelson Mandela the biggest mass welcome in the world in 1990 shortly after the great man was released after 27 years in South African prisons for fighting apartheid.

Dinkins, a tennis enthusiast who got the USTA National Tennis Center (now named for Billie Jean King) for the US Open built in Flushing, spoke movingly at the memorial service for tennis great and AIDS and race activist Arthur Ashe (for whom the Center’s stadium is named) in 1993 in Richmond, Virginia. At the conclusion of his remarks (the 19:56 mark in c-span.org/video/?37876-1/arthur-ashe-funeral-speeches), Dinkins said what he always said in eulogies, “It is said that service for others is the rent we pay for space on earth.”

In this case, he added, “Arthur Ashe left us paid in full. Let him not look down and find any of us in arrears.”

David Dinkins is paid in full. As he always signed off, “Keep hope alive!”

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.