A unanimous four-judge panel of the New York Appellate Division in Brooklyn revived a gay dad’s petition to adopt his son, reversing a “clearly erroneous” decision by Queens County Family Court Judge John M. Hunt.

Hunt stated two reasons for dismissing the adoption petition: that the child was the result of what he termed “a patently illegal surrogacy contract” and that there was no authority under New York law for a parent to adopt their own biological child.

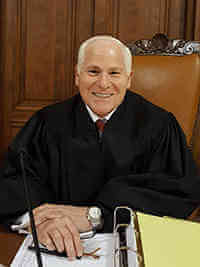

The June 26 Appellate Division opinion by Justice Alan D. Scheinkman clearly explained why both reasons are wrong, and the panel pointedly directed that the case be sent to a different Family Court judge to determine whether it was in the best interest of the child to grant the adoption, an easy call under the circumstances.

The Appellate Division decision is particularly timely given the State Legislature’s recent failure to pass a bill reforming surrogacy laws. Those laws are a legacy of the old New Jersey Supreme Court decision in the “Baby M Case” — which received sensationalistic media coverage — where a surrogate mother refused to give up custody of a child to its intended parents, spiriting the child out of the state to avoid giving it up. The New Jersey court ruled that the surrogacy contract was unenforceable, but that the biological father, who with his wife had contracted with the surrogate to carry the child, could seek custody. The trial court there ended up granting visitation rights to the surrogate while awarding custody to the biological father.

Out gay State Senator Brad Hoylman’s bill, which died in the most recent legislative session, would have permitted compensated surrogacy subject to substantial regulation.

In the Brooklyn case, a single gay man, identified only as Joseph P. in the court’s opinion, wanted to have children biologically related to him. In 2012, he arranged to have embryos created using his sperm and an anonymous donor’s eggs. A woman voluntarily agreed to be the gestational surrogate, signing an agreement to waive parental rights as the birth mother and consenting to Joseph’s adoption of the children. In 2013, twins, a boy and a girl, were born. A Family Court judge granted Joseph’s petition to adopt them without any fuss or drama.

In 2017, Joseph decided to have more children using the remaining frozen embryos. A woman friend agreed, again on a volunteer basis, to be the gestational surrogate, waived any parental rights, and consented to Joseph’s adoption of the child. In October of that year, John was born, and he has been in Joseph’s care ever since. As a matter of course, however, only the surrogate’s name is on the child’s birth certificate, since she is not married to Joseph, who therefore enjoys no legal presumption that he is the father.

Joseph ran into the roadblock of Judge Hunt, who misconstrued the surrogacy and adoption laws and dismissed his adoption petition, despite a social worker’s favorable home study that found him to be “a mature, stable, and caring person who intentionally created a family of himself, the twins, and John.” The social worker also wrote, “John’s adjustment appeared to be excellent, and it was clear that [Joseph], his twins, and John are a cohesive family unit.”

Justice Scheinkman provided a careful description of the laws governing surrogacy in New York. The Legislature provided that surrogacy contracts are unenforceable and treated as void. However, the only surrogacy contracts actually outlawed are those where the surrogate is compensated. It was clear to the Appellate Division that the Legislature did not mean to outlaw voluntary surrogacy arrangements, merely to make them unenforceable in the courts. Those who enter into a compensated surrogacy agreement face a small monetary fine and people who act as brokers to arrange such agreements are liable for a larger penalty. There is no penalty for voluntary, uncompensated surrogacy arrangements.

Even under existing law, New York trial courts have approved adoptions like Joseph’s in situations involving both voluntary and compensated surrogacy agreements. The Appellate Division’s careful analysis of the law made clear that the arrangement between Joseph and his gestational surrogate was not, as Judge Hunt stated, “patently illegal” — a conclusion Justice Scheinkman found to be “clearly erroneous.” Joseph’s petition, the appeals panel found, was not an action to “enforce” the surrogacy agreement. No such enforcement was needed since the surrogate already waived parental rights and consented to the adoption.

The Appellate Division also found no basis for Hunt’s finding that a biological father may not adopt his own child. Hunt had asserted that the adoption “would confer rights upon a parent which already existed.” Scheinkman pointed out the error there. Since only the surrogate’s name is on John’s birth certificate, she was the only legal parent.

“Here,” Scheinkman wrote, “the appellant, an otherwise qualified ‘adult unmarried person,’ seeks to adopt a child in order to gain legal and social recognition for the parent/ child relationship already existing between himself and the child. The Family Court disallowed it on the ground that there is no authority for a parent to adopt his or her biological child. We disagree.”

Nothing in the adoption statute precludes Joseph’s adoption of John, and Scheinkman cited several unusual cases where courts approved adoptions of children by their biological fathers. While conceding that “the issue we consider here is relatively novel and there is little by way of precedent,” the court stated that what cases there were supported allowing the adoption.

“The appellant, at present, has no legal relationship with the child,” observed the court, and the gestational mother did not seek to have a legal parental relationship with John. “Thus, an adoption of this child by the appellant would create a legal parent-child relationship where none previously existed, while severing a legal relationship with the gestational mother that exists solely as a legal abstraction with no physical or emotional manifestation.”

Joseph could, alternatively, pursue an order of filiation, based on proof that he is the biological father, but that route, Scheinkman wrote, would be a “shallow remedy,” since it would impose on Joseph only some of the obligations of parenthood while not providing him “with judicial authorization to make decisions on behalf of the child” that a parent would ordinarily make. He would then have to initiate a custody proceeding, a time-consuming process where the “ostensible adverse party would be the gestational surrogate who had already renounced her own tie to the child.”

The court concluded that allowing a biological parent to adopt a child born through gestational surrogacy “complies with the purpose of the adoption statute and should be permitted where, as in all adoption cases generally, the proposed adoption is in the best interests of the child.”