Pulitzer Prize winning author reads his debut novel, now a film, in Central Park

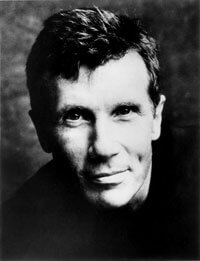

A good author tells you everything about his characters and almost nothing about himself. A good author photo will say even less. Before meeting author Michael Cunningham at an East Village bar where he was helping to toast a younger, lesser-known writer (who talked about the crystal meth epidemic, among other things), the only description I had of Cunningham was “roughshod.” It resonated in a profile about his work on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Hours.” The description had a nice ring, but was more apropos his beat-up leather jacket than the strapping genius in a tight white pocket tee who saddled up to the bar. Think Peter Weller as William S. Burroughs on a casual Friday.

The conversation that followed was just as layered, and no less fascinating. Help-a-brother-out quickly emerged as a theme as we skidded from rent-boys to Colin Farrell, from S&M sex to Jackie Collins. The Cincinnati-born New Yorker easily connected the dots between the writer he helped out the night before and another “kid with no money”—Peter Gaitens—who adapted and starred in a stage version of his novel “Flesh and Blood” last summer.

This summer finds Cunningham back in the city, this time reading from his 1990 debut novel “A Home At The End of The World” in Central Park on July 29, just days after his adapted screenplay for that film hits the big screen. Farrell, the Irish bad boy, stars as the Cincinnati kid querelling his way through the Glover family home, headed by a pot-smoking Sissy Spacek, before hightailing it to New York City on a Greyhound bus. By the time we finish, that single word “roughshod” had more holes in it than a shotgunned Burroughs’ paint can and a new portrait emerged. A picture that was funny, generous, sexy, kind, and nothing if not complicated.

TONY PHILLIPS: Last night we discussed crystal meth, Blondie, hustlers… At one point I thought we were all going to repair to Max’s Kansas City for dinner.

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM: I know, I know. It was fun. It could have been a night of readings about Afghanistan and I would have done it.

TP: I feel like the ruminations on crystal we heard onstage last night are our Afghanistan. The elephant was kind of in the room.

MC: It’s really poison. I’ve seen good men go down over crystal meth. It’s rich white people’s crack. And yeah, I think any attempt to get our brothers and sisters to lay off is a good thing. At the same time, I know why people love drugs. I get it. And I think we should live and be healthy, but I can’t get too stern about drug use. I mean, life is hard and drugs are fabulous. I understand why people are drawn to them.

TP: Has any of the Virginia Woolf fascination that’s popped after “The Hours” surprised you?

MC: Since “The Hours” came out, especially the movie version, Virginia Woolf has moved from an obscure figure of English letters into a position of considerably more prominence. “Mrs. Dalloway” was all over the best-seller list after the movie.

TP: Do you think her tragic end is a necessary part of her legend?

MC: Sure. She’s one of those artists who inspire people to focus as much on her life and death as they do her work. Sylvia Plath is often treated the same way, not so much in terms of her poetry as in terms of her life and her suicide. Anne Sexton, Jack Kerouac, there are a number of people whose colorful lives and premature deaths seems as interesting to people as their work.

TP: The caliber of talent your work draws is just remarkable. I thought not only Cherry Jones, but that entire, huge cast of actors in “Flesh and Blood” last summer was astounding.

MC: They were fantastic, weren’t they? Cherry Jones is a genius, one of the great living actors. That production took a long, long time. Peter Gaitens contacted me years and years ago. He was just a kid with no money. He wanted to do a stage adaptation and I thought “Great.” And then Peter and I worked closely together over a number of years. We had a lot of workshop productions.

TP: And now you’ve joined the ranks of screenwriters and adapted other material. Tell me about that.

MC: Well, “A Home at the End of the World” is a movie! I loved it. It was great. And I did write the screenplay for that. I was on the set the whole time. I worked very closely with Michael Mayer, the director. I looked at the dailies all the time. I even rewrote stuff as it went along. I was sitting with Colin Farrell and Sissy Spacek one night toward the end of the day’s shoot. We were looking at the next day’s scene and I thought, you know, this could be really better than it is and I wrote a new version, on notebook paper. They took it home and memorized it and we did the new scene the next day.

TP: I love that you’re working with Colin and also ushering in a new facet to his career. Would you say he plays gay?

MC: You know, Colin isn’t exactly gay in the movie though he very much loves another man. Colin’s character is extremely ambiguous sexually. He’s in love with everybody. More than anything, I’m happy to have been instrumental in giving Colin his first really serious complicated dramatic role. It’s the first movie in which he’s not just shooting people. And he’s fantastic.

TP: Does this film mark a move towards a more ambiguous definition of sexuality?

MC: What I hope we’re moving toward, and what I’m very interested in, is not really the ambiguity of people’s sexuality. I prefer to think of it as the complexity of people’s sexuality. As the revolution moves into its fourth decade, we’re beginning to appreciate that more. The fact that somebody is gay or lesbian or transgender or bisexual tells you almost nothing useful about that person. You and I are both gay men. Though I don’t know you at all, I strongly suspect that our sexualities are enormously different. The mechanics of our attraction, what gets us off, who we love… The fact that it’s directed—primarily or entirely—toward men narrows it down a little bit, but there’s still so much to know and talk about. I have at least one straight male friend whose sexuality is more familiar to me than is the sexuality of a gay friend of mine who is deeply into S & M and role-playing and really likes guys pissing on him. That’s entirely fine with me, but what gets the straight guy off makes more sense to me even though it’s directed at women.

TP: Tell me about how you do your work.

MC: Part of what I do is maintain my own delusions about the realness of this invented world. And if too much time goes by without my re-entering it, I become too aware of the fact that it’s just invented. If I’m with it every day, and pretty much at the same time every day, I can actually believe in it as a parallel reality. The big trick about writing a novel is just remaining explosively and intimately connected to it over the years it takes to write. It will take me three months to write a scene that you’ll read in five minutes. Anything else I write, I’m done with before my enthusiasm starts to fade. I don’t need to keep talking myself into it, whereas with a novel I do. There’s always a point when it starts to lag and I think I’m sick of this. I hate this. I don’t want to do this anymore. But of course, you let yourself go or you end up at the age of 75 with a hundred openings to novels.

TP: Is the writing process still mysterious for you?

MC: The process itself sheds a lot of its mystery. When you’re younger––just starting out––and you have a good day and then a bad day, it can make you crazy. I always thought ‘Okay, well, that good day that I had last week… how much sleep did I get, what did I eat?’ There’s this desperate attempt to recreate the circumstances that made a good writing day happen.

And then as time goes on, you begin to understand that there’s really no way to predict when you’re going to feel productive and when you’re not. If you just come in and try to do it everyday to the best of your ability, you understand it’s a job like any other. On the other hand, at its heart, it feels entirely mysterious to me. I don’t know where it comes from or how I do it. I know craft things, but on a deeper level, I have no idea.

TP: Is anyone else involved in that process?

MC: My first and most vital sounding board is actually Kenny [Korbett], the guy I’ve lived with for 16 years now. I take a passage as far as I can until I just can’t see it anymore and then Kenny is the first person I show it to. He is a truly brilliant reader for me. He’s utterly merciless, which is a good thing in the abstract [laughs], but not always such a good thing at the moment. But Kenny is very much the first reader I have in mind. Kenny’s depth, vast intelligence, and sense of humor are very much foremost in my mind as I work.

TP: Has the process of adapting “A Home At A Home At The End of the World” suggested any original screenplay ideas for you?

MC: Absolutely. I’m just finishing an adaptation of somebody else’s novel––a novel called “Evening” by Susan Minot—which I loved doing. Then I have to finish this novel I’m working on which I hope to do by summer and then I’m going to write an original screenplay for Michael Mayer to direct.

TP: Can you talk about the new book?

MC: You know, it’s still percolating. I can tell you a little bit. It’s very different, though it is three parts like “The Hours.” It’s three interconnected novellas, each in a different genre. There’s a ghost story, a thriller, and a science fiction story, but they all involve the same characters and they relate in very complicated ways.

TP: Do you ever get star-struck?

MC: You know, I haven’t. I don’t know why. I’m not especially nervous around celebrities.

TP: But Meryl? Come on!

MC: I know, I know. Meryl is a big thing. And I’ve gotten to know her and she’s lovely and fun and funny. She’s great. She does a great job of immediately making it as unweird as possible that she’s Meryl Streep and you’re not [laughs]. She’s very personal and direct and not the least bit grand, but we had something to do together, something to talk about. I wouldn’t go up to a celebrity at a party and say I love you. That would be too weird. Meryl and I were on this project together and flying back and forth together to LA. It was very easy.