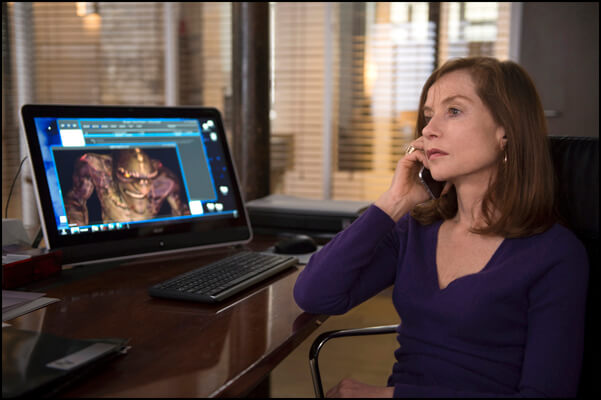

Kim Min-hee and Jung Jae-young in Hong Sang-soo’s “Right Now, Wrong Then.” | GRASSHOPPER FILM

Judging from his 17-film oeuvre (made in only 20 years), here’s a list of things South Korean director Hong Sang-soo likes: filmmakers such as himself, young women who are attracted to them, zoom lenses, soju (an indigenous Korean wine, equivalent to sake), complicated narrative structures. Hong has built a personal vocabulary and aesthetic as distinctive as any director who’s emerged in the time in which he’s been working.

Unfortunately, Americans have had a hard time keeping up with him, unless they attend film festivals avidly. I keep expecting his latest film to be his American breakthrough, but many of them haven’t even received distribution here. The films that have opened always closed in a week or two.

Hong’s work recalls French New Wave directors like Eric Rohmer and Alain Resnais, but its narrative playfulness is accessible, even if it demands an active spectator. I can even see connections between his films and “Groundhog Day.”

Director Hong Sang-soo finally has a shot at an American breakthrough

But Hong would probably need to be American — or at least cast an American star like Julianne Moore, instead of French actress Isabelle Huppert, who has appeared in two of his films — to find an audience here. Thankfully, the plucky new distributor Grasshopper Film is trying its luck with “Right Now, Wrong Then.”

Filmmaker Ham (Jung Jae-young), who’s often just referred to as “Director,” has arrived at the Suwon Film Festival a day early. Killing time at an outdoors hall, he meets a young female painter, Heejung (Kim Min-hee). She professes to admire his work, although conversation reveals that she hasn’t actually seen any of it. The two head to her workshop, where she puts the finishing touches on a colorful painting. Then they go out for sushi and soju, eventually having a lengthy drunken talk. It’s clear that they’re attracted to each other, but he’s married.

The next day, he appears in front of a small audience at the festival and gives a rambling answer when asked to give a concise summary of what film means to him. Then, around the hour mark, Hong’s film begins again, replaying the same situations with somewhat different dialogue and behavior.

A few films into his career, Hong seemed to discover the zoom lens and he hasn’t looked back since. While it was popular in the ‘60s, and filmmakers like Robert Altman and Roberto Rossellini made eloquent use of it, it quickly became a tiresome device; one French critic complained about the “boom of zoom.”

In Hong’s hands, the zoom lens enables him to vary the long takes he favors. He uses it 32 times in “Right Now, Wrong Then.” Sometimes it reinforces his characters’ essential isolation by suddenly focusing the camera on one of them. At other times, it allows him to reframe the image without moving the camera. The possibilities of the zoom lens seem endless in Hong’s hands.

The first part of “Right Now, Wrong Then” is actually called “Right Then, Wrong Now” onscreen, causing me to wonder if I’d gotten the title wrong. The differences between the two halves are sometimes minimal, sometimes major. For instance, Heejung uses orange paint in the first half and green paint in the second half. More importantly, she and Ham have a friendly discussion about painting in the first half and an unpleasant argument in the second half.

Sometimes, Heejung contradicts herself in the same ways. She complains about having no friends and then takes Ham to a party thrown by one of them. The film’s centerpiece — the extremely long take where Ham and Heejung drink soju and eat sushi — comes across differently in the two parts. Ham and Heejung seem to have fun getting drunk at first; later on, she drinks much less — this comes after she says she’s given up drinking and smoking — and his drunken antics have an ugly, desperate edge. This air of desperation only continues at the party Heejung takes him to.

Hong must know that his films often play like male fantasies; after all, he titled one of them “Woman Is the Future of Man.” Ham has a magnetic ability to attract women, but he also seems to be a pathetic drunk. This duality isn’t rare for a Hong protagonist. The same kind of scenario, playing out in a Woody Allen film, would wind up with Heejung becoming Ham’s girlfriend.

Hong is too self-aware to play the fantasy through to its obvious conclusion. He clearly identifies intimately with characters like Ham, but he creates universes to separate himself from them. Quantum physics meets the French New Wave in “Right Now, Wrong Then,” and the results don’t feel like anything I’ve seen before outside the Hong filmography.

RIGHT NOW, WRONG THEN | Directed by Hong Sang-soo | Grasshopper Film | In Korean with English subtitles | Opens Jun. 24 | Film Society of Lincoln Center, Francesca Beale Theater, 144 W. 65th St. | filmlinc.com | Metrograph, 7 Ludlow St., btwn. Hester & Canal Sts. | metrograph.com